In the eleventh post of I4I’s month-long campaign to mark International Women’s Day 2023, using data from both the IHDS and a survey conducted in rural Bihar, Rithika Kumar finds that migration-driven male absence is leading to the feminisation of everyday political engagement in rural India. This is through an alternate pathway: women are empowered despite remaining financially dependent on the household. However, she finds that the periodic return of migrant men and the dominance of joint family systems constrains this positive effect and doesn't fundamentally alter household dynamics.

Join the conversation using #Ideas4Women

Daksha Devi was sitting on a bench with some other women at the civil court in the city of Araria, Bihar when I met her. She was waiting at the parking lot for her lawyer, who was consulting with clients on a table under a tree nearby. Showing me the affidavit that she was carrying in her jute bag, she told me she was at the courthouse that day regarding a family feud that had resulted in over ten cases being levelled against her family. Her maalik saab (her husband) was a migrant who was currently in Delhi earning for the family, and she was dealing with lawyers, arranging paperwork, and attending court hearings on this case. Daksha Devi is one of millions of women in migrant households who serve as the primary interlocutors of the household with the state. The presence of these women in traditionally male-dominated arenas like courthouses, block offices, village squares and panchayat bhavans symbolises the shifting contours of local political engagement in patriarchal contexts and communities sending migrants to faraway cities.

India is home to over 100 million economic migrants who spend several months in a year away from home. While migrants themselves remain understudied, we know very little about the political lives of women like Daksha Devi who are often left behind by these men. In this article, I underscore an obvious but highly underappreciated fact of economic migration – that it is a form of ‘male absence’ from patriarchal households, which has implications for women’s political lives. I argue that the routine yet temporary absence of men from women’s lives is resulting in the feminisation of everyday political engagement in migrant-sending communities.

Studies from across the world have demonstrated that intra-household dynamics and unequal distribution of resources between male and female household members inform lower levels of female political engagement (Verba and Nie 1972, Iversen and Rosenbluth 2010, Brulé 2020, Khan 2021). In patriarchal societies with gender-biased norms, male members occupy a higher household status and gatekeep female presence even beyond the household (Agarwal 1997, Jayachandran 2015), including in the political sphere (Gottlieb 2016, Prillaman 2021, Cheema et al. 2021). In this article, I argue that the absence of male gatekeepers due to migration, even if temporary, is an important and overlooked driver for female olitical empowerment.

Data and methodology

My argument is supported by multiple forms of data collection and a mixed-methods approach. First, to inform my theoretical expectations, I use data collected from over 70 semi-structured interviews with elites, and resident men and women in migrant-sending communities in rural Bihar, a key source of internal migrants in India. Next, to test these expectations, I draw on a large, nationally representative panel dataset – the Indian Human Development Study (IHDS) for 2005-06 and 2011-12. Using this dataset, I utilise a difference-in-differences framework1 to overcome well-known issues of endogeneity due to self-selection into migration. This framework enables me to compare women with migrant husbands in wave two of the IHDS and women with co-resident husbands in both waves to provide causal estimates of the effect of migration on women’s private and political lives. Finally, to validate the results of the aforementioned analysis, with a far richer and more contextually sensitive set of measures of both male migration and female political engagement, I also conducted my own survey of 1,900 women across 150 villages in the Araria district in Bihar.

Measures of female political engagement

I measure female political engagement along a range of measures used in the IHDS, including political discussion within the household, knowledge of benefits, membership to political parties and attendance in public meetings. My own survey collects detailed information on other routine forms of engagement, including claim-making or contact with local actors like bureaucrats, village heads and other intermediaries for different services. I also collect information on visits to local state institutions and other variables like the propensity to run for political office.

To provide evidence on the plausible mechanisms driving female political engagement in the context of male migration I use three main indices: mobility (ability to traverse local boundaries), decision-making (say in important household decisions) and status within the household (access to financial resources and ability to eat with others in the household).

Anecdotal evidence from interviews suggested that the household primarily relied on remittances to manage finances. Women might supplement household income through agriculture work or rearing cattle but the responsibility to financially provide for the family rested on the man. As a resident in the Palasi block in Araria put it, “as long as my husband is able-bodied, he will earn for the family.” Moreover, women have fewer opportunities to participate in income-generating activities given their added responsibilities for agriculture, household and childcare work in their husband’s absence. Therefore, the traditional division of labour within the household seems to persist in migrant households, leaving women with few opportunities to participate in income-generating activities. I test this by measuring the effect of migration on three different forms of work: i) farm work, ii) non-farm business, and iii) wage labour. I use this analysis in order to argue that male migration activates an alternative pathway that does not require women to be economically empowered in order to be politically engaged.

Findings

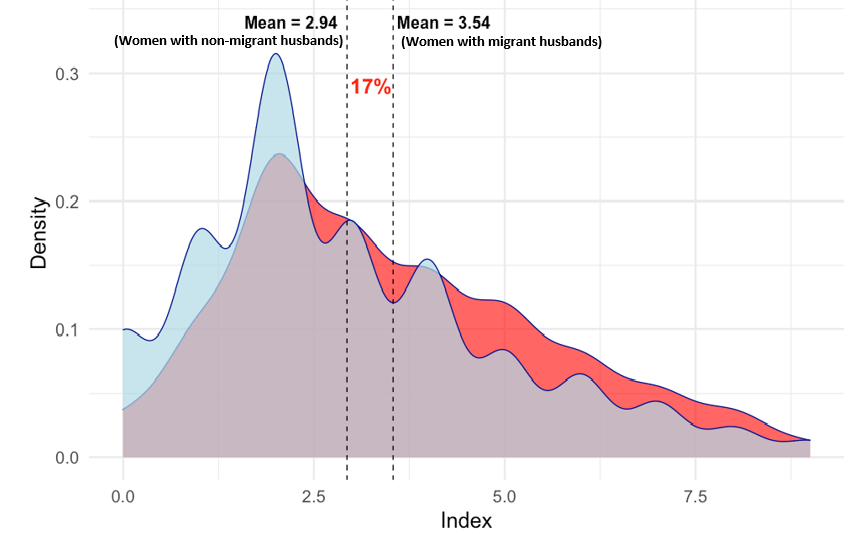

Routine engagement with the state and local actors forms an integral part of accessing welfare services in rural India. Observational data from the IHDS reveals that male migration increases the likelihood of women’s political discussion with their husbands, and their civic knowledge and engagement outside the household by up to 10%. These results are corroborated by more detailed measures from my own survey. In migrant households it is women who are stepping into the role of engaging with the state on behalf of the household. I find that, on average, wives of migrants are 17% more likely to contact local state actors and other bureaucrats to make claims for their rights and to access services (Figure 1). These results are also substantively meaningful; they eclipse the size of effects due to other well-established drivers of political engagement like education.

Figure 1. Women’s contact with local state actors, measured by a claim-making index

Notes: i) Claim-making index is an additive measure of the state actors contacted by an individual for welfare provision. ii) The red graph is for women with migrant husbands making contact with the state, and the blue graph measures the same for women co-residing with their husbands. iii) N= 1904 women (with migrant and non-migrant husbands) in Araria, Bihar.

Source: Author's own survey (2022)

The analysis also reveals that male migration thrusts women into the public sphere, as they routinely traverse local boundaries, putting them in contact with a diverse set of individuals. More mobility gives women access to information that they are otherwise not likely to be privy to. This information is utilised by women to demand services and contribute to household discussions, including discussions on politics. Within the household, I observe complementary shifts for involvement in decision-making and access to cash.

The results of this study are robust and clear: male migration is leading to an increase in female political engagement with the state.

Left-behind or left-ahead: Contextualising findings

While the opportunities for female political empowerment due to internal male migration are unambiguous, it is likely to have a more complex impact on women’s lives, due to three reasons. One, migration does not fundamentally alter the traditional division of labour within the household. In fact, male migration weakens the demand for female labour force participation: I find that women with migrant husbands are 2-7% less likely than women with co-resident husbands to participate in income-generating activities, since they are left with little to no time, given the increase in household and farm labour demands. Therefore, the opportunity for substantive financial autonomy among women married to migrant husbands remains absent. This is as an important result, since it contradicts existing theories that identify economic autonomy as a prerequisite for female political empowerment.

Two, the nature of internal male migration in India is temporary. Men return home periodically and retain ties with home communities even while they are away. I find that upon their husband’s return, the gains in women’s mobility and access to financial resources within the household dissipate. Yet not all empowerment is lost, as migrant wives continue to partake in key household spending and political discussions following their husband’s return. Because women have gained expertise and knowledge from managing activities concerning the household, men are likely to rely on them to make decisions even after they return. These findings illustrate the constrained but important gendered political impact of male migration.

Three, male migration creates a disruption in the household’s status quo which challenges the existing social order by thrusting women into the public sphere. However, the ability of women to utilise this opportunity is impeded by the practice of patrilocality, where women move into their husband’s homes and live with his extended family. I find that the presence of older male and female family members crowds out the gains to female political engagement due to male migration. The absence of their migrant husbands is insufficient to overcome the stronghold of household hierarchies and social norms on female presence beyond the household.

Conclusion

Despite the large scale of employment-related male migration in India, we know very little about the political lives of the women these men often leave behind. I argue that migration-driven male absence activates an alternate pathway for female political empowerment in regions where existing resource-based explanations cannot explain women’s poor political participation. The feminisation of quotidian practices of political interaction in migrant-sending communities occurs even while the traditional division of household labour is retained; women need not be financially independent or develop an identity outside the household as a prerequisite to greater political engagement.

Such major transformations have often required equally significant shocks to the household to be realised, including permanent absences of men. I show that even temporary absences that do not yield such major structural improvements still open opportunities for improved political engagement. Male migration creates lasting changes to household dynamics with respect to decision-making. However, male migration is unable to fundamentally alter household structures of financial inequality, hierarchy between members and norms around women’s presence beyond the household, which remain unchanged once men return.

Note:

- Differences-in-differences is a technique used to compare the evolution of outcomes over time in similar groups, where one experienced an event – in this case, having a migrant husband – which the other did not.

Further Reading

- Brulé, Rachel (2020). “Reform, Representation, and Resistance: The Politics of Property Rights’ Enforcement.”, The Journal of Politics, 82(4): 1390-1405. Available here.

- Cheema, Ali, Sarah Khan, Asad Liaqat, and Shandana Khan Mohmand (2021) “Canvassing the Gatekeepers: A Field Experiment to Increase Women Voters’ Turnout in Pakistan.”, American Political Science Review, 117 (1): 1-21.

- Gottlieb, Jessica (2016) “Why might information exacerbate the gender gap in civic participation? Evidence from Mali.”, World Development, 86:95-110.

- Iversen, T, and Frances McCall Rosenbluth (2010), Women, Work, and Politics: The Political Economy of Gender Inequality, Yale University Press.

- Khan, S (2021), ‘Count Me Out: Gendered Preference Expression in Pakistan.’ Unpublished manuscript. Available here.

- Prillaman, Soledad Artiz (2021), “Strength in Numbers: How Women’s Groups Close India’s Political Gender Gap.” American Journal of Political Science, 0(0): 1-21

- Verba, S, and Norman H Nie (1972), Participation in America: Social Equality and Political democracy, Harper & Row, New York

27 March, 2023

27 March, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.