In the fourth post of I4I’s month-long campaign to mark International Women’s Day 2023, Rajshri Jayaraman considers the negative correlation between high rates of co-residence with in-laws and low rates of labour force participation among women in India. She establishes a causal relationship between the two and explores three possible channels through which co-residence could reduce women’s employment – a negative income effect from accessing shared household resources; an increase in domestic responsibilities; and conservative gender norms which restrict women's agency.

Join the conversation using #Ideas4Women

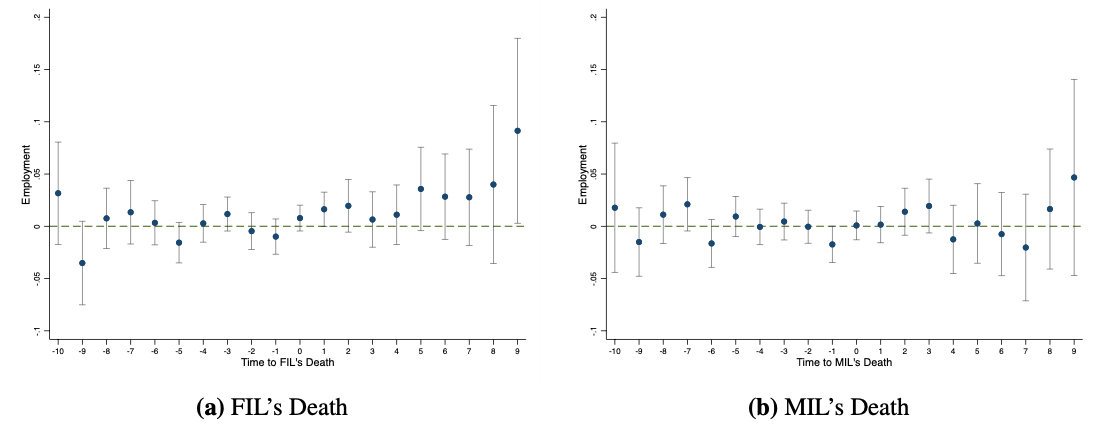

Women in India have one of the lowest rates of labour force participation in the world. They also co-reside with their parents-in-law at unusually high rates. Figure 1 shows that these two phenomena are negatively correlated over the lifecycle: in both the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS, 2005 and 2011) and the Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS, 2016-2019), employment among married women follows an inverted U-shaped pattern, rising until a woman reaches her forties and declining thereafter. Directly upon marriage, over 70% of married women in India co-reside with one or both parents-in-law. As employment rises with age, co-residence with parents-in-law declines as couples move out or in-laws die.

Figure 1. Married women’s employment and co-residence with parents-in-law (PIL)

How does co-residence affect women’s employment?

There are three reasons why the negative correlation in Figure 1 may be causal. First, co-residence allows for potential household income and asset sharing, and this may exert a negative (income) effect on women’s labour supply. Second, co-residence may impose additional domestic responsibilities on women, including cooking, cleaning, and eldercare, which detract from labour force participation. Third, norms of filial piety, which accord decision-making authority to elders in the family, may intersect with more conservative gender-based norms in older generations to impose additional social barriers to women’s employment.

The gender of co-residing parents-in-law matters in this context. Since asset ownership and decision-making authority in traditional Indian families tend to be vested in men, these three channels suggest that co-residing fathers-in-law may act as a greater deterrent to married women’s employment than co-residing mothers-in-law. This possibility is at odds with the caricature of the tyrannical mother-in-law in popular culture.

Research question and design

In recent research (Jayaraman and Khan 2023), we ask whether co-residence with fathers- and mothers-in-law reduces employment among married women in India. The challenge in answering this question is that co-residence with in-laws is a choice, and unobserved reasons for this choice may be correlated with a woman’s employment decisions. For example, if a husband gets a better job, a couple may be able to move out of the parental home into a nuclear household, and the wife may be able to stay at home in the new nuclear household. Alternatively, the birth of a child may prompt a married couple to move in with the in-laws who can provide extra support and resources for childcare. In general, observing a negative (or positive) correlation between co-residence and employment tells us nothing about the causal relationship between the two.

We address this endogeneity problem using two completely different approaches. First, we use the death of a father- and mother-in-law as an instrument for co-residence.1 This instrument is clearly relevant: it affects co-residence status because one cannot reside with a dead parent-in-law. However, questions about whether it is exogenous linger, because the death of a parent-in-law may have a direct impact on employment. Our second approach embraces this possibility by directly examining how employment of married women changes following the death of a parent-in-law, using difference-in-differences.2 We apply our first strategy to data from two different nationally representative household datasets – IHDS and CPHS – and exploit the high frequency data in the CPHS, which is administered every quadrimester (a four-month interval), to execute the second approach. Neither strategy is perfect but together, and across different datasets, they provide a very consistent answer to our research question.

Findings

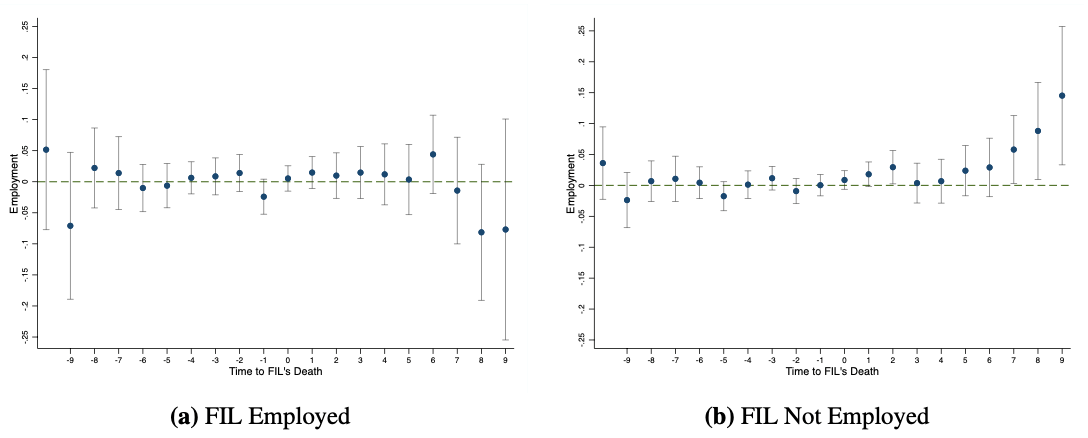

Our main finding is that co-residence with fathers-in-law reduces married women’s employment, but co-residence with mothers-in-law does not. Instrumental variable fixed effects estimates, which exploit variation in co-residence for a given woman over time, indicate an 11% (in the IHDS) to 13% (in the CPHS) reduction resulting from co-residence with a father-in-law. By contrast, co-residence with a mother-in-law has no significant effect on married women’s employment in either dataset. Conversely, as Figure 2 shows, CPHS difference-in-differences estimates indicate that married women’s employment increases following the death of a father-in-law, but does not significantly change following the death of a mother-in-law.

Figure 2. Married women’s employment response to the death of a father-in-law (FIL, left panel) or mother-in-law (MIL, right panel) by quadrimester

Note: The y-axis denotes changes in employment rate relative to the year before the event of a PIL’s death, with 95% confidence intervals for the point estimates. A 95% confidence interval indicates that if you were to repeat the study over and over with new samples, 95% of the time the true effect would be within the interval.

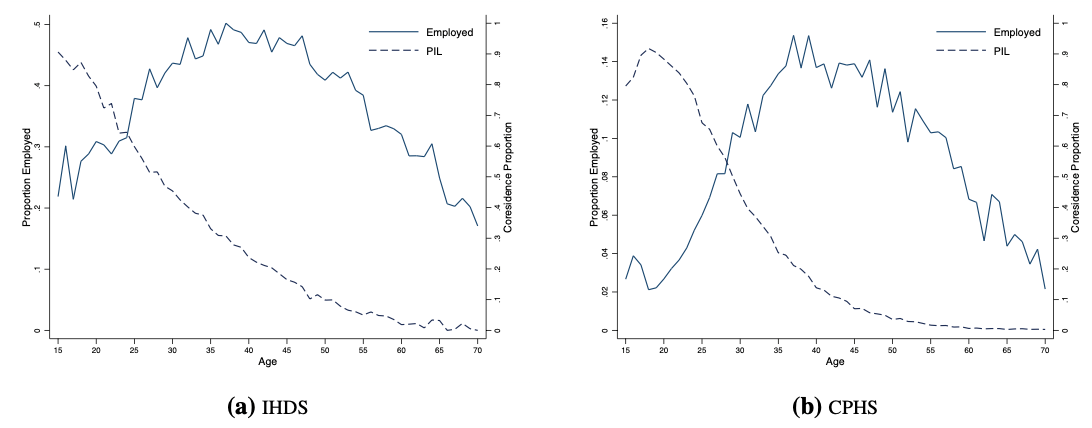

We also investigate three channels that may account for why co-residence with fathers-in-law tends to reduce married women’s employment. To begin with, we do not find support for the possibility that the opportunity to share in in-laws’ household income or assets exerts a negative income effect on a co-residing daughter-in-law’s labour force participation. For instance, if this mechanism were at play, one might expect that the death of an employed, income-earning father-in-law may compel a woman to work, while the death of a father-in-law who was not employed would not. Figure 3 shows that the opposite is true: the positive aggregate employment response shown in the left panel of Figure 2 is driven by the death of fathers-in-law who were not employed (right panel of Figure 3).

Figure 3. Married women’s employment response to the death of an employed (left panel) and not-employed father-in-law (FIL, right panel) by quadrimester

Note: The y-axis denotes changes in employment rate relative to the year before the event of a FIL’s death, with 95% confidence intervals for the point estimates

Second, co-residence with parents-in-law may increase a woman’s domestic responsibilities within the household, compromising her ability to work in the labour market. Using data from the 2019 Indian Time Use Survey, we find that there is some shift in time use away from employment to domestic activities when co-residing with a father-in-law. Co-residence with a mother-in-law is also accompanied by a shift in time use to domestic activities, with no corresponding change in time spent on employment. However, the shift in time use – a matter of minutes in one direction or another – seems too small for increased domestic responsibilities to be the full story.

Third, conservative gender norms, amplified by norms of filial piety, may constrain women’s agency. We find support for this channel: when married women co-reside with their in-laws, major decision-making authority is vested in the father-in-law rather than the husband; in the kitchen the co-residing mother-in-law, rather than her daughter-in-law or son, tends to hold sway. We also find that women who co-reside with parents-in-law have significantly less mobility outside the household, and less financial autonomy, both of which are likely to compromise their labour force participation.

Policy implications

At some level it should not be surprising that in a patriarchal society, fathers-in-law should matter for women’s employment. Yet, their role as a potential constraint on women’s employment has been largely ignored in both the popular narrative, as well as in research and policy design. Since restrictive gender-based norms tend to be internalised and enforced by the family, this seems like a marked oversight given the preponderance of filial households in India. Our results suggest that, in the Indian context, fathers-in-law should be considered when modelling household decision making and designing policy aimed at influencing social norms which might increase women’s employment in India.

Notes:

- An instrumental variable is used in empirical analysis to address endogeneity concerns. An instrument is correlated with the explanatory factor but does not directly affect the outcome of interest, and thus can be used to measure the true causal relationship between the explanatory factor (co-residence with a parent-in-law) and the outcome of interest (women’s employment).

- Differences-in-differences is a technique used to compare the evolution of outcomes over time in similar groups, where one experienced an event – in this case, the death of a parent-in-law – which the other did not.

Further Reading

- Jayaraman R and B Khan (2023), ‘Does co-residence with parents-in-law reduce women’s employment in India?’, Working Paper 747, University of Toronto, Department of Economics.

13 March, 2023

13 March, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.