This note summarises the findings of a survey conducted by students at IIT Delhi to evaluate the functioning of the PMGKAY scheme across Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Punjab. It reveals that many households did not receive their entitled ration during the pandemic, and highlights disparities in the states’ distribution efforts along with long-standing issues of the Public Distribution System like exclusion errors due to difficulty in obtaining ration cards for family members, and Aadhar-linkage.

On 23 December, the central government announced the roll back of the temporary Prime Minister Garib Kalyan Ann Yojana (PMGKAY) scheme. Piyush Goyal, the Union Minister for the Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution Ministry announced that the subsidised food grains under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) will continue to be provided for free from January 2023. “The free portion of that scheme [PMGKAY] has been added to the NFSA. Now, the entire quantity of 5 kg and 35 kg under the NFSA would be available free of cost. There is no need for additional food grains,” he was quoted as saying in media reports.

The PMGKAY scheme, launched in April 2020 – in response to the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdown imposed to mitigate it – provided an additional five kilograms of ration to existing beneficiaries under the NFSA. The government claimed that around 800 million priority households (PHH) and Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) card holders under NFSA had benefited from the PMGKAY scheme.

When the PMGKAY was operational, there were multiple reports of people not receiving the ration but few systematic studies of the problem. The discontinuation of the scheme from January 2023 presented a last chance (before recall issues would undermine such an attempt) to conduct field surveys to not only estimate the extent of exclusion, but also to audit the functioning of the scheme during Covid.

Survey design

A survey was conducted by students enrolled in a course on development economics at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. Designed by Dr. Reetika Khera, the survey was conducted in three states – Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Punjab – in the last week of January 2023.

Within these states, one sample district and one replacement district (to be surveyed in case the sample district was inaccessible) were randomly selected. From these districts, two sample and one replacement blocks, along with two sample and two replacement villages were randomly selected. Once the villages were identified, the list of NFSA beneficiaries in these villages was accessed through the states’ NFSA portal, and 20 sample and 10 replacement households were selected randomly. A total of 174 households were surveyed. A majority of the respondents belonged to landless households (69%) suggesting that the selection of NFSA beneficiaries was reasonably well-targeted. On average, respondents had 7 years of schooling and almost one-third (30%) of respondents were illiterate.

A survey instrument with questions across five sections was used to collect data on household characteristics, details of ration cards and purchases made, and details on agricultural activity.

Performance of PMGKAY

The findings of the survey revealed major lapses in the implementation of the PMGKAY. The average monthly entitlement for the PHH households was 55 kilograms based on household size, while for AAY households it was 59 kilograms. However, the survey found that the average purchase during the Covid-19 period was only 29.64 kilograms for PHH card holders and 32.14 kilograms for those with AAY cards. This shows that many cardholders did not receive the entitled amount of ration during the pandemic.

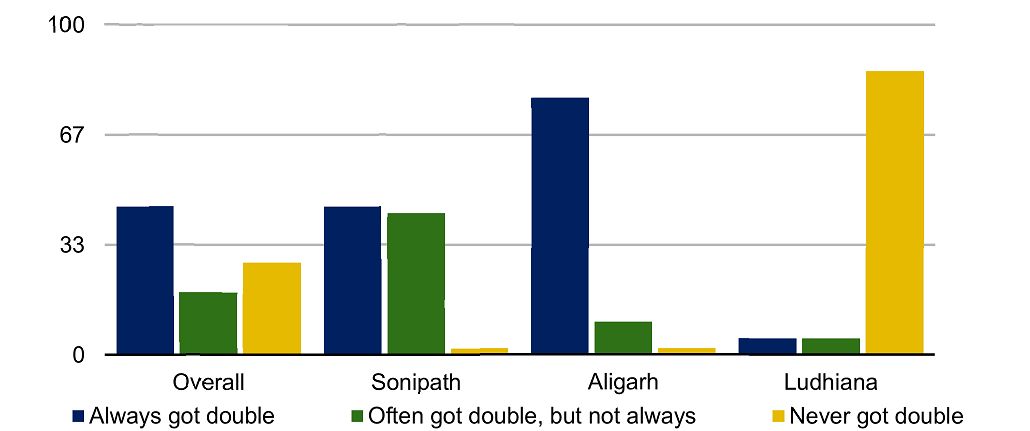

This was also corroborated by a question in the survey that asked people if they had received double the amount of ration during the pandemic (that is, twice a month, once under the NFSA and once, without charge, under the PMGKAY). Of the surveyed households, only 43% of the beneficiaries reported having always received both the entitlements under NFSA and PMGKAY. This figure was lower – only 35% – for landless households holding AAY cards.

In terms of implementing PMGKAY, Uttar Pradesh was the best performer. Of the three states, it had the highest number of respondents – 78% – who reported having “always” received double ration during the Covid-19 period (Figure 1). This was followed by Haryana, where, in Sonipat, 45% of the respondents reported always receiving double ration.

Figure 1. Proportion of households with reported regularity of ration distribution

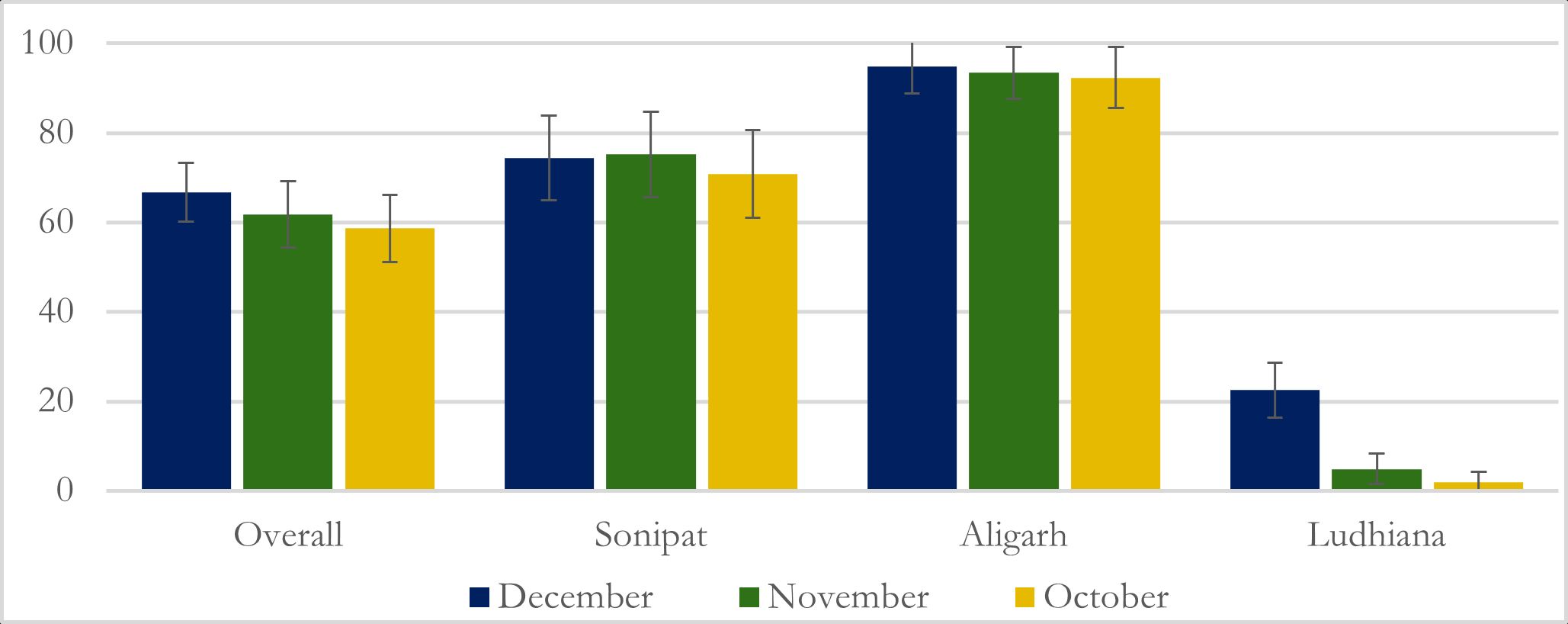

Based on recall, the survey asked the respondents about the quantity of purchase made in the last three months – October, November and December 2022. These figures were used to calculate the purchase-entitlement ratio, which is the purchases households were able to make from the PDS as a proportion of their total entitlement (see Figure 2). On this measure too, Uttar Pradesh emerged as the best performer, with 95% ration being purchased in December, and 93% in October and November. One of the reasons for this performance can be that woman-led self-help groups (SHGs) acted as dealers of ration in the surveyed villages. SHGs having charge of food grain distribution is associated with better distributional outcomes (Khera 2011).

Figure 2. Purchase entitlement ratio per person in PHH households, in percent

Note: The vertical bars show 95% confidence intervals. A 95% confidence interval means that if you were to repeat the experiment over and over with new samples, 95% of the time the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect.

The survey findings also reveal Punjab to be the worst performer. In Ludhiana, the survey found that as many as 86% of the respondents never received double ration. The purchase-entitlement ratio here was also the lowest, ranging between 22-25%, suggesting that over three-quarters of respondents were not able to purchase as much as they were entitled to. During the survey it was found that in violation of the norms of monthly distribution of ration, in Ludhiana, ration was distributed only once in six months. With this bi-annual distribution, malpractice and corruption levels are high. For instance, people may not have enough cash to buy six months grain and may forego some of it; if they are not around at the time of the distribution, they may have to forego all six month’s rations. Another explanation is that respondents were unable to report purchases accurately because of the long recall period. Awareness about the entitlement to additional ration under PMGKAY was also low in this region.

Around 80% of all respondents reported that they used the ration for self-consumption and 11% reported consuming only part of the ration. Of this 11%, many reported that they used part of the ration to feed their cattle. Encouragingly, there were not many complaints of poor quality of grain, although some households in Aligarh complained about the quality of salt. This finding clearly shows that, unlike the popular perception that beneficiaries were selling the ration in the open market, even the double ration was largely used for self-consumption.

Minimum Support Price and Public Distribution System

The survey instrument was also designed to estimate the number of households which were receiving ration under the PMKGAY scheme, while also selling their produce to the government at Minimum Support Price rates, thereby simultaneously benefitting from both. Our findings suggest that the overlap between the two is small, in part due to the high incidence of landless households in the sample (see Table 2).

More than two-thirds of the sample households were landless, and among those who did own land the average land holding size was 0.5 acres. Around 10% of the respondents reported that they sell food grains to the government. This proportion was highest in Aligarh, where the proportion of landless households (54%) was lowest among the survey districts.

Table 1. Households benefitting from PDS and MSP

|

|

Overall sample |

Sonipat |

Aligarh (Uttar Pradesh) |

Ludhiana (Punjab) |

|

Proportion (%) of landless households |

69 |

69 |

54 |

88 |

|

Average landholding size (among households that own land), in acres |

0.5 |

1.08 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

|

Proportion (%) of PHH households that cultivate either wheat or rice and sell to the government |

8.12 |

6.6 |

12.9 |

4.4 |

Lack of documentation and other exclusion issues

The survey also revealed other malpractices. In all the surveyed districts, most people did not have their ration cards – instead, they had a photocopy of the first page of their card and biometric authentication which was used to access PDS benefits. For instance, in Aligarh, the normal practice adopted by dealers was to collect the thumb impression of PDS beneficiaries at their home and distribute ration after two or three days.

On average, the household size was 6.4 in Aligarh, 4.6 in Ludhiana and 5.3 in Sonipat. In contrast, on average, the number of people within households registered for the ration cards was only 3.4, 3.4 and 4.9 respectively. This suggests that many people are being excluded from the PDS, even among entitled households.

In Aligarh and Sonipat, there were households which were not able to receive ration throughout the duration of the PMGKAY scheme because they did not have an Aadhaar card. Elsewhere too, respondents complained that adding members was difficult especially without Aadhaar. For instance, in Ludhiana, our team noticed some family members who hadn’t been added to the ration card and others who weren’t removed. Marriage was a major reason for this – daughters who got married were not removed from the ration card, and newly-wed daughters-in-law were not added. At the same time, newborns were also not added. In Aligarh, households without an Aadhaar card reported challenges adding new members to their ration card. If the daughter is married, the dealer deducts the amount of ration, even if her name was on the ration card, since dealers usually belong to the same locality and are aware of social events like marriages.

Conclusion

Our survey suggests that the PDS ration, which is mostly used for self-consumption, is an important part of a household’s food security. However, while it clearly establishes the need to provide ration to households, it also brought to light various violations of both PMGKAY and PDS policies, and highlighted issues of exclusion errors. We found lapses where, due to Aadhar linkage problems, eligible beneficiaries were kept out of the social safety net of PDS during a difficult time like the Covid-19 crisis.

Within the three surveyed districts, we found that the PDS performed the worst in Punjab, where most of the beneficiaries were not able to purchase the entitled amount of ration. This finding merits further investigation. The better results in Uttar Pradesh are also noteworthy because of the state’s poor performance in earlier studies (Drèze and Khera 2015, Gupta and Mishra 2018). They suggest that in the run up to the state elections, the state may have made efforts to make the PDS work better.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions made by Aazra Asif, Kavitabh Kumar, Saksham Sodani, Lavanya Ganesan and Neha Arya.

Further Reading

- Khera, Reetika (2011), “Revival of the Public Distribution System: Evidence and Explanations”, Economic and Political Weekly, XLVI (44&45): 36-50. Available here.

- Dreze, Jean and Reetika Khera (2015), "Understanding leakages in the public distribution system", Economic and Political Weekly, 50(7): 39-42.

- Gupta, Abha and Deepak K Mishra (2018), “Public Distribution System in Uttar Pradesh: Access, Utilization and Impact”, Indian Journal of Human Development, 12(1): 20-36.

13 September, 2023

13 September, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.