Subcontracting relationships with larger firms are considered key to facilitating the growth of informal enterprises. Using four rounds of National Sample Survey data on Indian informal manufacturing during 2001-2016, this article examines the nature and patterns of subcontracting linkages for informal, family-based household enterprises. It finds that subcontracting linkages are starkly different from the dynamic kind expected to facilitate growth and transition of informal firms.

The informal economy remains a major source of livelihoods for the vast majority of India's workforce. It is expected that with rapid economic growth, the formal segment would generate employment for this population, along with better growth opportunities for the informal enterprises to transition into larger, more modern, formal enterprises.

In this context, larger enterprises developing subcontracting linkages with informal enterprises (where the former hires the latter to produce parts, components, or assemblies for further value addition (National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), 2010) is considered an important channel to facilitate growth of informal enterprises and, thereby, to aid such a transition. These linkages are expected to strengthen with economic growth, and to enable market access, credit access, transfer of technologies, and development of entrepreneurial capabilities and human capital for the informal enterprises (Ranis and Stewart 1999, Arimah 2001, Chen 2006, Meagher 2013, Moreno-Monroy et al. 2014, Hampel-Milagrosa et al. 2015).

The informal sector in India is heterogeneous, comprising both family-based household enterprises that do not employ wage workers (own-account enterprises) and relatively larger micro-entrepreneurial enterprises that hire wage workers (establishments). The former, which have relatively low productivity and are mostly subsistence-driven, constitute an overwhelming 85% of India’s informal sector. Given the absence of a capital-wage labour relationship, these can be referred to as non-capitalist enterprises. A transformation of the informal sector would involve these non-capitalist enterprises growing into micro-capitalist establishments in the informal sector or larger firms in the formal sector.

In recent research (Kesar 2024), I study the pattern and nature of subcontracting linkages in informal household enterprises in India's manufacturing sector – how these linkages have evolved, and whether they are of the dynamic kind that can play the expected role of facilitating accumulation, growth, and potential transition of these enterprises. To do this, I analyse data from repeated cross-sections of four rounds of the NSSO’s quinquennial survey of unincorporated enterprises (one at every time point), covering a period of India’s high economic growth from 2000-01 to 2015-16.1

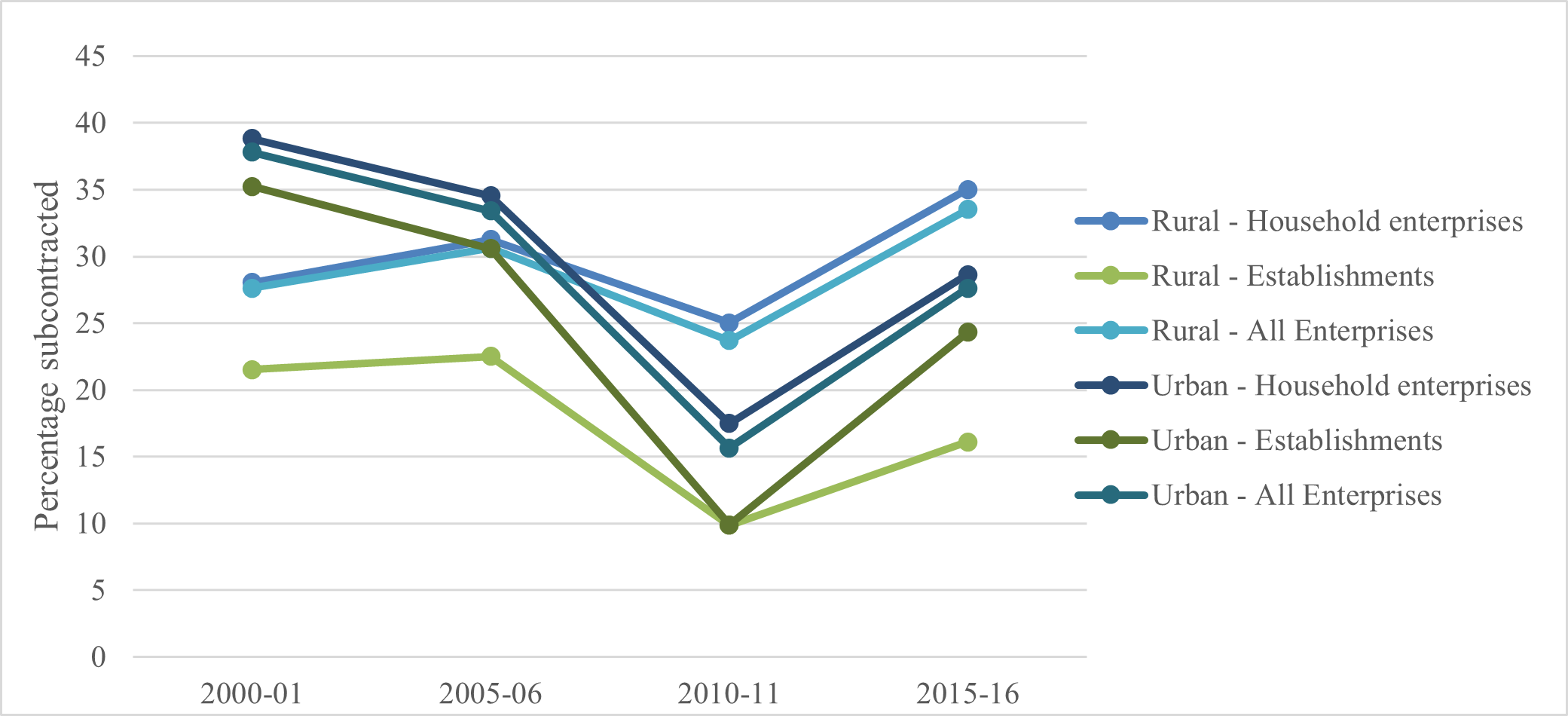

Incidence of subcontracting

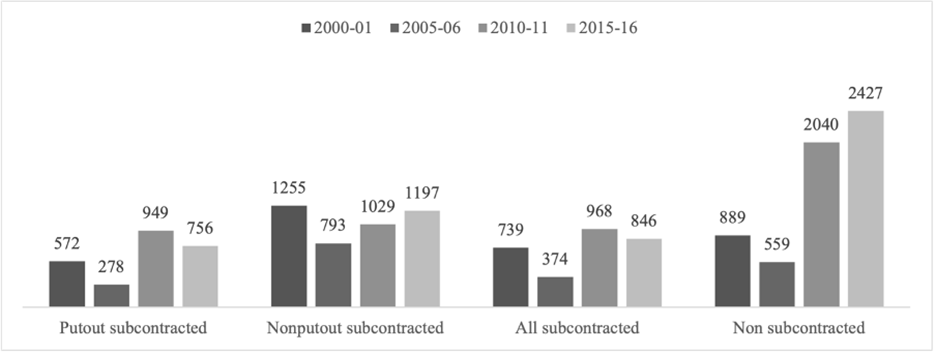

Less than 30% of informal enterprises have been in a subcontracting relationship at any point of time during 2001-2016. Overall, during this period, the incidence increased slightly in rural areas but fell by nearly 10 percentage points in urban areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Incidence of subcontracting in rural and urban areas, 2001-2016

The possibilities of transition of subcontracting enterprises

To assess the potential of informal household enterprises to grow and transition, I estimate values for an ‘accumulation fund’ that an enterprise can use towards investment after paying for all expenses, rent and interest payments and setting aside funds for consumption by family workers.2

Strikingly, on average, subcontracted enterprises retain a much lower accumulation fund than non-subcontracted ones. Over the 15-year period, the difference has risen dramatically – with the ratio of average accumulation funds between non-subcontracted and subcontracted enterprises increasing from 1.2 to 2.9. By 2015-16, while the average accumulation fund of non-subcontracted enterprises had grown to about 2.7 times its 2000-01 levels, it had largely stagnated for the subcontracted enterprises (Figure 2). The difference persists even upon controlling for differences in enterprise characteristics and other industry and state-level variations.

Figure 2. Accumulation fund of subcontracted and non-subcontracted household enterprises

Source: Author’s calculations using 56th, 62nd, 67th, and 73rd rounds of NSSO survey data.

Note: The values depicted are real monthly values, in 2015-16 rupees.

Focusing on subcontracted household enterprises, I find that the vast majority (87% to 97%) receive raw materials and design specifications (89% to 95%) from the contractor and supply their entire produce (83% to 92%) to the parent enterprise (Figure 3). In contrast, only a small proportion of subcontracted household enterprises receive any equipment from the contractor and often use home-based tools, indicating a lack of technology transfer.

Subcontracting relations in which the parent enterprise controls the key aspects of the production process without formally owning the subcontracted enterprise, which undertakes production upon direction from the parent enterprise, resemble a traditional ‘putting-out’ system (Bhattacharya et al. 2013, Basole et al. 2015). Characterising enterprises that exhibit all three characteristics – receiving raw materials, design specifications, and supplying solely to the parent enterprise – as put-out enterprises, I find that about 75-81% of subcontracted household enterprises operate under such a relationship (Figure 4). The subcontracted enterprise loses autonomy over production and sale, effectively becoming an appendage of the parent firm. On the other hand, while these enterprises are contracted almost like wage workers by the parent firm, they also do not become internal to it. The put-out firm thus appears as a hybrid of a worker and an enterprise, as also noted by Sanyal (2007).

Figure 3. Characteristics of subcontracted household enterprises

Source: Author’s calculations using 56th, 62nd, 67th, and 73rd rounds of NSSO survey data.

Note: The values depicted are real monthly values, in 2015-16 rupees.

Figure 4. Proportion of put-out and non-put-out of subcontracted household enterprises

Despite being most closely aligned with – and subsumed under the economic logic of – the parent firm, the put-out enterprises, on average, also have the least possibility among different types of household enterprises (including non-subcontracted and non-put-out subcontracted) to grow, as captured by its accumulation fund (Figure 5). The difference continues to persist even after controlling for state, industry groups, and rural/urban location variations.

However, note that despite there being a striking gap between put-out and non-put-out subcontracted enterprises at the beginning of the period, the gap has somewhat narrowed over time due to a stagnancy in the net accumulation fund (NAF) of the latter. Therefore, being in a put-out relationship not only appears to be a dominant form of subcontracting in the informal sector, alternative, more autonomous subcontracting relationships also seem to have ceased to offer a significantly better alternative in terms of growth possibilities.

Figure 5. Monthly average NAF of putout, non-putout, subcontracted, and non-subcontracted enterprises

Source: Author’s calculations using 56th, 62nd, 67th, and 73rd rounds of NSSO survey data.

Note: The values depicted are real monthly values, in 2015-16 rupees

Who enters subcontracting relations?

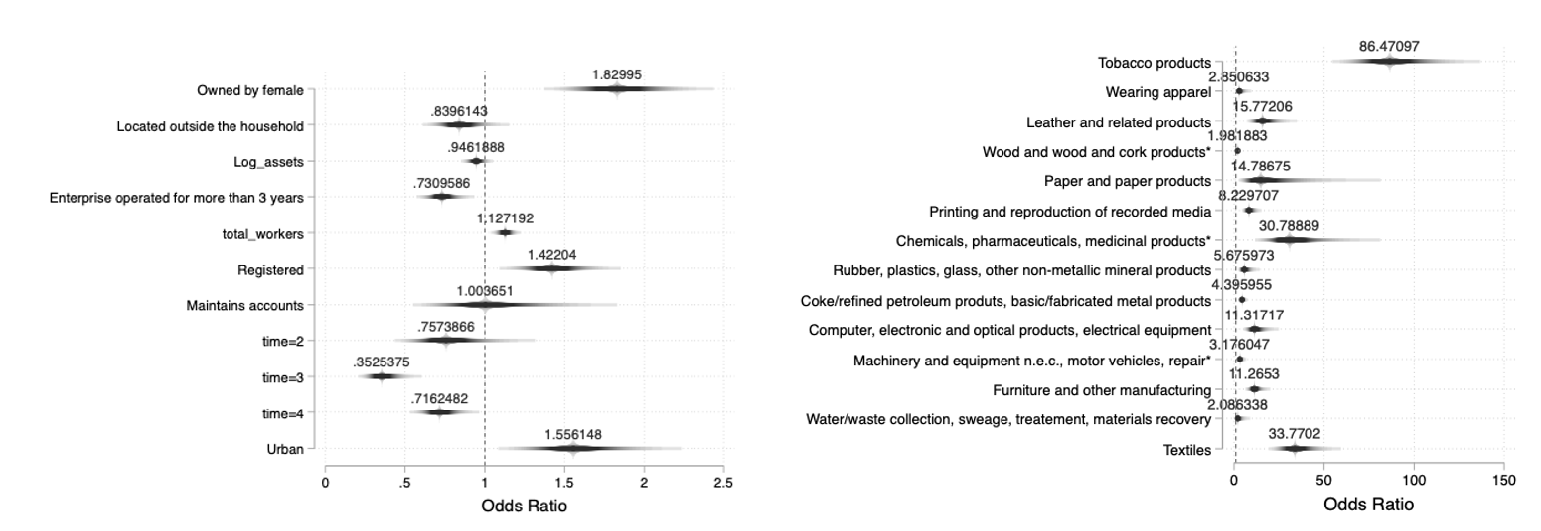

Finally, I investigate what kinds of enterprises enter subcontracting relationships. I estimate this using a ‘maximum likelihood estimation’3, and represent the results using an odds ratio.4 The gender of the enterprise owner, rural/urban location, duration of operation, and industry group are significant factors influencing the likelihood of an enterprise entering subcontracting relations. For example, on average, over the period of analysis, female headed enterprises are 1.8 times more likely to subcontracting relationships relative to non-female headed ones (Figure 6). Moreover, among the major industry units, the incidence of subcontracting is particularly high in tobacco products and textiles.

Figure 6. Likelihood of being subcontracted, by enterprise characteristics

Source: Author’s calculations using 56th, 62nd, 67th, and 73rd rounds of NSSO survey data.

Notes: (i) The figure presents results from Logit maximum likelihood estimation, with binary dependent variable model. (ii) The binary dependent variable takes the value 1 if the enterprise is subcontracted and 0 if it is not subcontracted. (iii) Explanatory factors include gender of the enterprise owner, whether the location of the enterprise is within or outside the household, log value of assets owned or hired, whether the age of the enterprise is less or more than three years, total number of workers, registration status, accounts maintenance, time, sector (rural/urban), industry groups, state zones. (iv) Odds ratio reported. Robust standard errors, clustered at state levels.

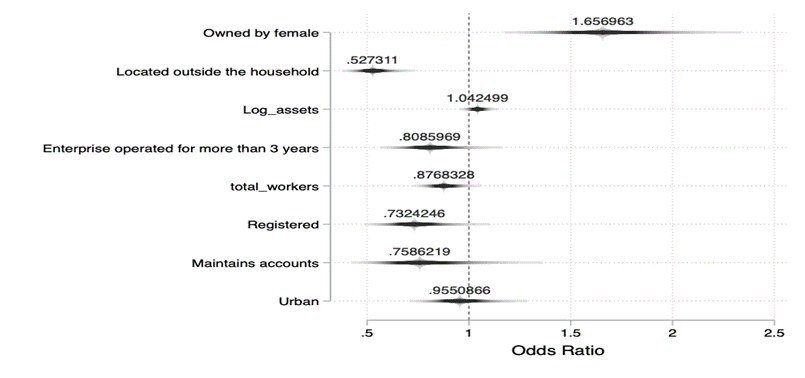

Focusing on subcontracted household enterprises, the gender of the enterprise owner and the enterprise's location (within or outside the household) are the strongest factors to be in put-out relationships. Female-owned enterprises are about 1.7 times more likely, and enterprises located within the household are almost twice as likely, to enter put-out relationships (Figure 7). An ‘Oaxaca-Blinder’ decomposition exercise5 indicates that the gender of the enterprise owner also explains about 79%, and location explains another 24% of the difference in accumulation fund between put-out and non-put-out subcontracted enterprises. This highlights the significance of a feminised workforce and access to household spaces in the put-out subcontracting processes and in its lower growth potential.

Figure 7. Likelihood of being put-out among subcontracted enterprises, 2001-2016

Notes: (i) The figure presents results from logit maximum likelihood estimation, with binary dependent variable model. (ii) The binary dependent variable takes the value 1 if the enterprise is put-out and 0 if it is non-put-out. (iii) Explanatory factors include gender of the enterprise owner, whether the location of the enterprise is within out outside the household, log value of assets owned or hired, whether the age of the enterprise is less or more than three years, total number of workers, registration status, accounts maintenance sector (rural/urban). Additional controls include time points, industry groups, state zones. (iv) Odds ratio reported. Clustered robust standard errors, clustered at state levels.

Given the relatively disadvantaged position of women, who face barriers to accessing credit and markets due to social norms and patriarchal structures, as well as for those located within households, being in a put-out relationship offers assured demand for products. However, being embedded in such relationships is associated with the least autonomy and lowest possibility among all household enterprises to grow and transition into larger enterprises. From the parent firm’s perspective, such linkages effectively subsidise their production costs by contracting to home-based female workers that have lower bargaining power and by gaining access to non-commodified household resources, such as tools and space.

Despite having limited chances to grow, subcontracted enterprises, especially the put-out ones, may enter in subcontracting relationships to meet the consumption needs of the household owning them, which may otherwise be difficult to secure. However, the prevailing subcontracting linkages in the Indian informal sector, even during its peak period of economic growth, sharply contrast with the dynamic subcontracting linkages celebrated in the literature as a channel for facilitating the transformation of informal enterprises, and therefore of the informal sector.

I4I is now on Substack. Please click here (@Ideas for India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- 2015-16 is the last available round of this survey. The Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation recently released some key results from the survey of unincorporated enterprises for 2021-22 and 2022-23 annual rounds, which are expected to replace the quinquennial survey rounds. The data for these survey rounds are yet to be released.

- Following Kesar and Bhattacharya (2020), I impute a pseudo wage for family labour and owners working in the enterprise, based on what a similar informal enterprise that hires wage workers pays as average wage. I expect this pseudo wage to be an underestimation (and therefore the accumulation fund to be an overestimation) of what these enterprises are likely to set aside for their consumption, since estimates from other studies based on nationally representative data for India (Kesar 2023) show that, on average, households deriving their primary income from informal self-employed household enterprises have higher consumption than those deriving primary income from informal wage workers. This only makes our results stronger.

- This estimates the parameters from a logistic regression model that maximises the likelihood function for the probability of being subcontracted.

- Odds ratio estimates the likelihood of an enterprise with a particular characteristic, such as being female-owned, to be subcontracted relative to an enterprise without that characteristic. An odds ratio of one suggests an equal likelihood of being subcontracted for both categories (that is, female and non-female owned) while an odds ratio of greater than one suggests a higher likelihood for the category exhibiting the characteristic, and vice versa.

- An ‘Oaxaca-Blinder’ decomposition is a statistical method that explains the difference in the means of a dependent variable between two groups by decomposing the gap into within-group and between-group differences.

Further Reading

- Arimah, Ben C. (2001), “Nature and Determinants of the Linkages between Informal and Formal Sector Enterprises in Nigeria”, African Development Review, 13(1): 114-144.

- Basole, Amit, Deepankar Basu and Rajesh Bhattacharya (2015), “Determinants and impacts of subcontracting: evidence from India’s unorganized manufacturing sector”, International Review of Applied Economics, 29(3): 374-402.

- Bhattacharya, R, S Bhattacharya and K Sanyal (2013), ‘Dualism in the Informal Economy: Exploring the Indian Informal Manufacturing Sector’, in S Banerjee and A Chakrabarti (eds), Development and Sustainability, Springer, New Delhi.

- Chen, M (2006), ‘Rethinking the Informal Economy: Linkages with the Formal Economy and the Formal Regulatory Environment’, in B Guha-Khasnobis, R Kanbur and E Ostrom (eds), Unlocking Human Potential: Concepts and Policies for Linking the Informal and Formal Sectors, Oxford University Press, New York.

- Hampel-Milagrosa, Aimee, Markus Loewe and Caroline Reeg (2015), “The Entrepreneur Makes A Difference: Evidence on MSE Upgrading Factors from Egypt, India, and the Philippines”, World Development, 66: 118-130.

- Kesar, Surbhi and Snehashish Bhattacharya (2020), “Dualism and structural transformation: The informal manufacturing sector in India”, The European Journal of Development Research, 32, 560-586.

- Kesar, Surbhi (2023), “Economic Transition, Dualism, and Informality in India”, Review of Development Economics, 27(4): 2438-2469.

- Kesar, Surbhi (2024), “Subcontracting Linkages in India's Informal Economy”, Development and Change, 55(1): 38-75.

- Meagher, K (2013), ‘Unlocking the Informal Economy: A Literature Review on Linkages between Formal and Informal Economies in Developing Countries’, WIEGO Working Paper No. 27, Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing.

- Moreno-Monroy, Ana I, Janneke Pieters and Abdul A Erumban (2014), “Formal Sector Subcontracting and Informal Sector Employment in Indian Manufacturing”, IZA Journal of Labor & Development, 3(1): 1-17.

- National Sample Survey Organisation (2010), ‘Instructions to Field Staff Volume-I Design, Concepts, Definitions and Procedures Socio-Economic Survey NSS 67th round (July 2010 - June 2011)’, NSSO, Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation.

- Ranis, Gustav and Frances Stewart (1999), “V-goods and the Role of the Urban Informal Sector in Development”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 47(2): 259-288.

- Sanyal, K (2007), Rethinking Capitalist Development: Primitive Accumulation, Governmentality and Post-Colonial Capitalism, Routledge, New Delhi.

27 June, 2024

27 June, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.