India’s credit landscape has been undergoing major changes in recent years. In this post, Sengupta and Vardhan discuss five key trends – consumerisation of bank credit, decline in bank deposits, growth of credit from the bond market, NBFCs re-emerging as important credit institutions, and relatively new ‘alternative investment funds’ catering to small/low-rated firms. They emphasise the need for a dramatic change in the regulatory and policy approach.

The Indian credit landscape has been undergoing some major changes over the last few years. If these persist, they could dramatically alter credit allocation in the economy, which in turn will have repercussions for economic growth as well as for the distribution of the country’s output. As the new government takes over in June and charts the road ahead for the economy, it will need to confront these challenges.

Strengthening of balance sheets in the banking sector in the aftermath of large-scale capital infusion in State-owned banks and robust recovery of the sector post-Covid-19 seem to have created a celebratory mood among analysts and policymakers. This, however, is taking the attention away from some deeper structural issues. For instance, the banking system has always been the primary, formal provider of commercial (that is, non-government) credit in India. While it continues to be so, other sources of credit are also becoming prominent such as the bond market and NBFCs (non-bank financial companies). A private credit market is also developing, thereby occupying the space left unaddressed by the bond market and banks. Banks, on the other hand, have become crucial vehicles for providing credit to the vast Indian retail sector. All these changes will also usher in the need for adjustments by the two main regulators governing this space, namely the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). Given the critical role played by credit in fostering economic growth, the repercussions of these new developments are important to understand for informing the design of policies and regulations over the next five years, in order to ensure sustained economic growth as well as financial sector stability.

For several years before the pandemic, the Indian banking sector was embroiled in a crisis that manifested in the form of rapidly rising non-performing assets (NPAs) on the balance sheets of banks. NPAs were triggered by large-scale defaults in the corporate sector, with the bulk being reflected on the balance sheets of inadequately capitalised public sector banks. By FY2017-18, gross NPAs in India had reached almost 14% of total loans – the highest among emerging economies. As a result of a series of corrective actions initiated by the RBI, several rounds of recapitalisation by the government, resolution of NPAs under the new Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC, 2016), and banks’ own heightened risk aversion, banks today are in a significantly better position with healthier, well-capitalised balance sheets. However, in the process, the patterns of bank lending have undergone a major transformation, even as other elements of the credit ecosystem have come to play a crucial role.

In an earlier I4I article (Sengupta and Vardhan 2023), we had discussed the trends in and composition of credit growth in the Indian economy over the last decade across various classes of borrowers, and thrown light on the emergence of some of the new trends in this landscape. In this follow-up article, we take a deeper dive into some of those emerging trends. While these trends were visible before the pandemic they have become even more pronounced as the economy emerged out of the pandemic.

Changes in the credit landscape

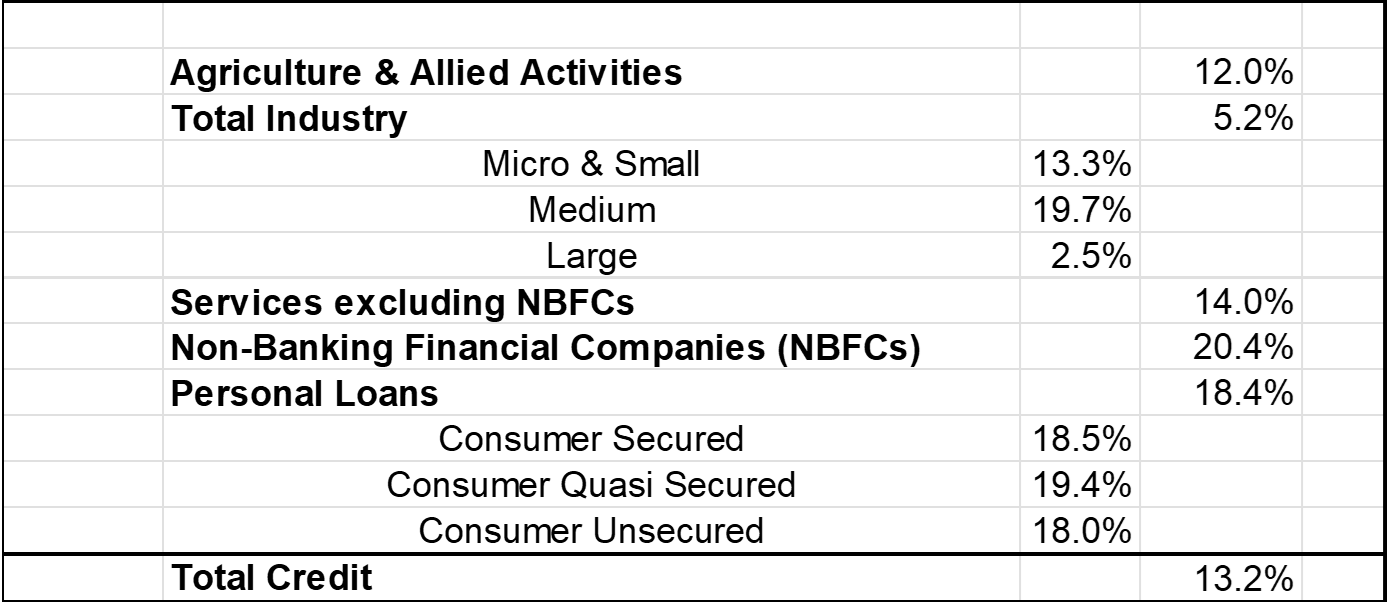

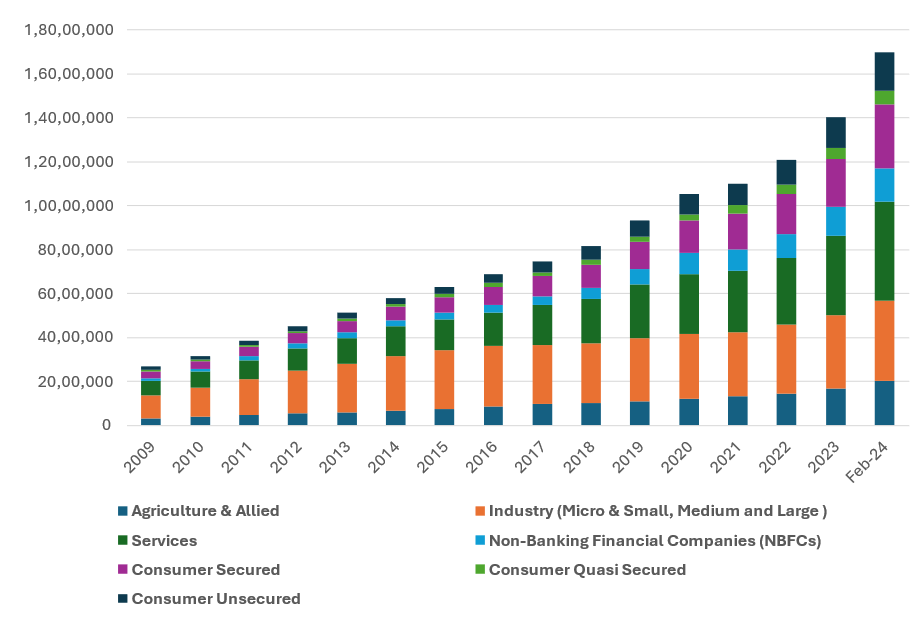

Five emerging trends are worth noting in this context. First, there has been a steady ‘consumerisation’ of bank credit, a trend we first wrote about in Sengupta and Vardhan (2021). In Figure 1 below, we show the changes in sectoral deployment of bank credit over the years. In FY 2010-11 the share of consumer credit in total bank credit was only 19%. By FY2023-24 this increased to around 33%. Nearly half of this credit is unsecured or quasi-secured (secured against weak collateral), which makes it riskier. In the post-pandemic period, much of the growth in bank credit has in fact been driven by growth in consumer lending. In FY2023-24, while overall non-food bank credit1 grew by 13% on a year-on-year basis, consumer credit grew by a remarkable 18.5%. In Table 1 we summarise the compounded annual growth rates (CAGR) of key segments of bank credit from FY2018-19 to FY2023-24.

Table 1. Growth rate of sectoral bank credit, FY2018-19 to FY2023-24

Note: The numbers for FY2023-24 are for 11 months until February 2024, which was the latest data available at the time of writing of this article.

Source: RBI data.

Figure 1. Sectoral deployment of bank credit from FY2008-09 to FY2023-24

Source: RBI data.

Note: Numbers for FY2023-24 are for 11 months until February 2024, which was the latest data available at the time of writing of this article.

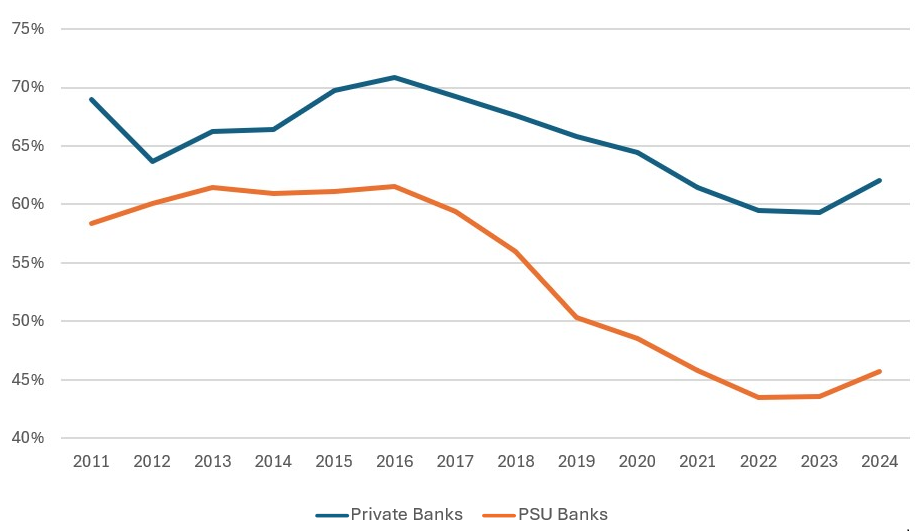

In contrast, the share of industry in bank credit declined from 44% in FY2010-11 to 28% in FY2023-24. This is partly the outcome of continued risk aversion in the banking sector. After getting badly scarred by the NPA crisis of 2015-2019, banks still seem cautious to lend to industry. In Figure 2 we show the risk aversion of the banking sector, measured as the ratio of risk-weighted assets to total assets (a lower ratio implies greater risk aversion), of a select sample of private and PSU (public sector undertaking) banks accounting for roughly 90% of the banking system. Note that the uptick in FY2023-24 is mostly due to the increased risk weights NBFCs and unsecured consumer credit.

Figure 2. Risk aversion in the banking system: Ratio of risk-weighted assets to total assets

Source: Authors' summary based on investor presentations of 22 private sector and 12 public sector banks.

This may have also been due to consistently weak credit demand from the industry. After years of sluggish performance, private sector investment still has not picked up in a substantial manner. It is true that within industry, bank credit to medium industry grew at almost 20% and that to small industry at around 13%, but this was primarily driven by the Extended Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS). Under this scheme, announced by the government in the wake of the pandemic, MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises) could get collateral-free bank loans of up to Rs. 3 trillion with 100% credit guarantee. For 10 years before the pandemic, the CAGR of bank credit to MSMEs was merely 4%. Between FY2018-19 and FY2023-24, credit to large industry grew only by 2.5%.

Secondly, in the post-pandemic period, banks have been struggling to raise deposits. Deposit growth has consistently lagged behind credit growth by 4-5 percentage points for the last three years. This could be happening partly because household financial savings as a share of GDP (gross domestic product) has fallen from 7.2% in FY2021-22 to 5.1% in FY2022-23. At the same time, Indian household savings have shown a migration from bank deposits into alternative investments options, mostly equity and debt markets through mutual funds. Data from the National Stock Exchange show that the total number of registered investors in the equity market crossed 90 million for the first time in February 2024, of which the majority are retail investors. The fall in bank deposit growth constrains the growth of bank credit.

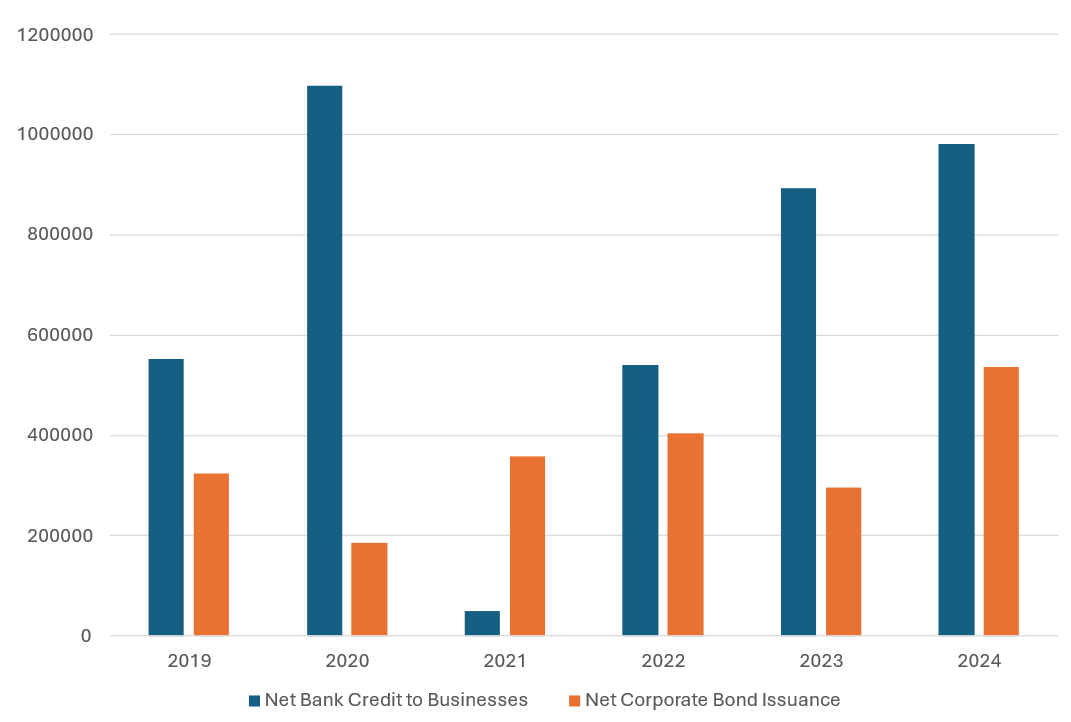

Third, as the banking sector systematically withdrew from lending to the industry, the corporate bond market emerged as an important player in this landscape. Between FY2010-11 and FY2023-24, the share of bonds in overall non-government credit went up from 14% to 21%. Growth rate of credit from the bond market outpaced credit from banks. From FY2018-19 to FY2023-24, while the overall bank credit grew at 12%, bond issuances by businesses grew at 13%. Corporate bonds are now cumulatively close to 70% of net bank credit. Close to 70% of the bond issuances are by NBFCs, both public and private. In Figure 3, we show the share of banks and bonds in annual incremental credit to businesses.

Figure 3. Incremental bank credit to businesses and net bond issuances (in Rs. crore)

Source: Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI); Prime Database, RBI.

Notes: (i) Numbers for FY2023-24 are for 11 months until February 2024, which was the latest data available at the time of writing of this article. (ii) Net bond issuances for FY2023-24 are estimated on the basis of December 2023 numbers.

Fourth, NBFCs have re-emerged as important credit institutions over the last few years. Notwithstanding the short-term troubles triggered by the default of the IL&FS (Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services) in September 2018, which set NBFCs back for some time, between FY2010-11 and FY2021-22, net credit from NBFCs (excluding credit to NBFCs from banks and the bond market) grew at a staggering CAGR of 21%. Expanding at a compounded rate of 16%, they continued to outpace the growth of bank credit from FY2021-22 to FY2023-24 – which stood at roughly 12%. While in FY2010-11 the share of NBFCs in total commercial credit was around 12%, this increased to 25% by FY2023-24. Over two-thirds of NBFC credit currently goes to the retail sector.

Finally, a nascent private credit market seems to be developing in India through alternative investment funds (AIFs). According to the Prime database, annual credit extended by these funds increased from around Rs. 15,000 crore in FY2018-19 to Rs. 66,600 crore in FY202324 , a growth rate of around 37% per year. These funds raise money from institutions, both domestic and global, as well as from high net-worth individuals (HNI) and channelise it to low-rated firms (rated A to BB)2, as compared to the public bond market where only high-rated firms can issue bonds. These AIFs can become an alternative source of credit for the smaller and/or low-rated firms that are unable to get credit either from the banks or from the bond market. Set up as funds, AIFs also have greater flexibility in structuring credit. However, credit AIFs are relatively new entities in India, and hence their governance needs to be monitored carefully. At present, the regulatory dispensation on AIFs is the same as that for equity and credit AIFs, which may have to change to address specific risks and governance challenges that are distinct for the two types.

Repercussions of the changes

The changes mentioned above can have far-reaching consequences not only for the Indian financial sector but also the economy at large.

First, the Indian corporate bond market is highly skewed and accessible only to large, established, and high-rated firms. Over 80% of bonds issued are rated AA and above. There are very few takers for bonds rated A and below that are likely to be issued by the smaller firms (with higher perceived credit risk). It is important to note that the largest capital pools investing in Indian bond markets are insurance, pension (including provident funds) and mutual funds. All these pools are averse to investing in bonds rated below AA, even when investment guidelines issued by their regulators permit them to do so.

In contrast, the median rating for bank loans to industry is BBB (based on anecdotal evidence through our discussion with bankers; there is no data on this in the public domain). The decline in overall bank credit to industry therefore implies that low-rated firms are the ones whose credit supply has relatively gone down.

Together, these two trends suggest that, over the last few years, the section of commercial borrowers who traditionally could only access bank credit (that is, smaller, and riskier firms) are no longer able to do so, with the ECLGS years being an exception. Moreover, as households turn investors in equity and debt markets from depositors in banks, and banks’ supply of funds keeps getting squeezed, this trend of lower credit to smaller firms may get further accentuated.

Secondly, a lot of credit seems to be going to the consumer sector, both from banks and NBFCs. This steady rise of consumer credit may pose systemic risk concerns. In particular, the growth of unsecured consumer credit at over 20% for the last few years increases the likelihood of defaults on consumer credit. Unlike corporate defaults that can get spread out over a few years, consumer credit bust can happen much more suddenly and is more susceptible to contagion. In the corporate NPA crisis of 2015-2019, the main credit institutions impacted were banks. In the event of a consumer credit bust now, in addition to banks, NBFCs and fintech firms are likely to get affected as well.

While the top NBFCs are now able to access the bond market and also get funding from banks, a contagion of consumer defaults can rapidly erode the credit rating of the NBFCs that have lent to the defaulting consumers. As a result, NBFCs can rapidly lose their access to funds. Since banks have exposure both to NBFCs and retail customers, such a contagion will also affect them both directly and indirectly. Depending on the severity of the defaults, this can soon morph into a systemic crisis.

Anecdotal evidence shows that households are now taking fresh loans to refinance existing ones. This can be risky, especially as the RBI is making it more difficult for banks to lend to retail customers by demanding higher capital for such lending, leading to reduction in the availability of new consumer loans. Banks may resort to higher levels of securitisation and adopt an ‘originate to distribute’ model of consumer credit.

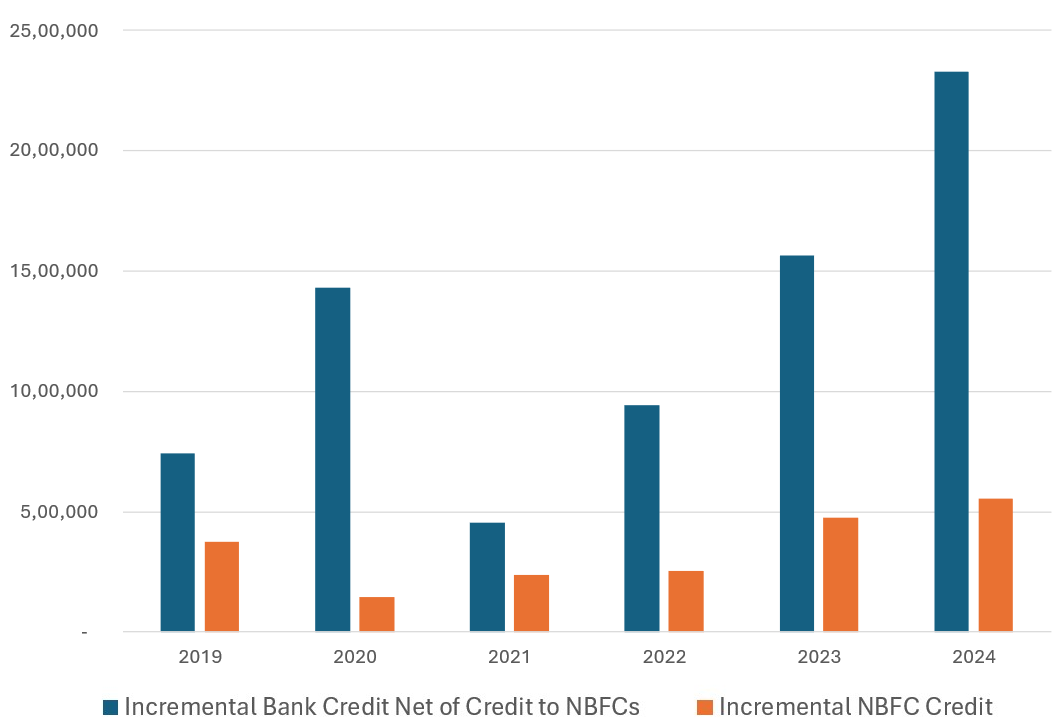

Figure 4. Incremental bank and NBFC credit (in Rs. crore)

Source: RBI data.

Notes: (i) Numbers for FY2023-24 are for 11 months until February 2024, which was the latest data available at the time of writing of this article. (ii) NBFC numbers for FY2023-24 have been annualised on the basis of half-yearly numbers.

Overall, these trends suggest a very significant shift in the credit landscape. Credit seems to be moving from the supply side (businesses) to the demand side (consumers) of the economy. Considering the state of economic development of India and the relatively low level of per capita GDP, this move appears to be premature. Even within consumer credit, the growth is fastest in high-risk, unsecured or quasi-secured, end-use unspecified credit that is driving consumption. On the liabilities side banks are facing increasingly intense competition from mutual funds and capital markets for household savings.

Regulatory and legal implications

As a consequence of the rise of the bond market in the commercial credit space, both through public and private markets (that is, credit AIFs), and movement of household savings from the banking system to capital markets, the regulatory oversight for a significant portion of financial intermediation, including credit, is moving away from the RBI to SEBI. Currently, nearly half of the incremental commercial credit is under each of these two regulators. This calls for better harmonisation of their regulatory approaches – given the interconnectedness across institutions and markets – to ensure that there is no regulatory arbitrage.

Regarding consumer credit, the big elephant in the room now seems to be the lack of a well-defined and modern legal framework to deal with the bankruptcy of individuals. Data from Lok Adalat and the Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) mechanism show that the current recovery rate from individual defaulters is less than 3% for unsecured consumer credit, which is the fastest growing segment. So far, the RBI has been somewhat reactive in its approach in dealing with risks emanating from this sector. It has recently increased the risk weights on unsecured consumer and NBFC credit from banks by 25%. However, as Indian banking shifts from the provider of credit to businesses to the provider of credit to consumers, the regulatory approach may need to undergo a profound change. Regulations in areas such as income recognition and asset classification norms, credit cost provisioning, reporting and disclosures, etc., are all targeted towards managing systemic risks arising from commercial credit; these will now need to change to reflect the rising share of consumer credit.

Conclusion

The credit ecosystem in India seems to be at a crucial inflexion point. If the trends that we highlight here persist over the next few years, we shall witness a very different credit landscape that will have long-lasting implications for the growth rate as well as for risks to the economy. This new world of credit will also demand a dramatic change in the regulatory and policy approach. Proactively assessing these shifts and making changes to policy and regulations will make the transition easier and safer.

The views expressed in this post are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the I4I Editorial Board.

I4I is now on Substack. Please click here (@Ideas for India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content

Notes:

- Non-food bank credit includes credit to four major sectors – agriculture, industry, services and personal loans.

- Rating firms use different designations to identify a bond's default probability - "AAA" and "AA" (high credit quality or low default probability) and "A" and "BBB" (medium credit quality) are considered investment grade, while credit ratings below these are considered low credit quality (or high default probability)

Further Reading

- Sengupta, R and H Vardhan (2021), ‘‘Consumerisation’ of banking in India: Cyclical or structural?’, Ideas for India, 23 July.

- Sengupta, R and H Vardhan (2023), ‘The post-pandemic credit landscape in India’, Ideas for India, 8 May.

20 May, 2024

20 May, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.