In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, weaving is often a family enterprise. Using data from over 1,800 households, this ongoing mixed-methods evaluation by Patel et al. shows that households with multi-generational weaving businesses earn more in weaving revenue and have greater household incomes relative to households with only one generation of weavers. However, it notes that these gains in productivity are not equally distributed across the household, as they do not translate into greater agency for the women weavers who are part of family-owned businesses.

India has a rich history of textile production, with the earliest evidence of textile trade dating back to the Indus Valley civilisation in 3,000 BCE (Crill 2015). With their vibrant patterns, bold colours and lightweight fabrics, Indian textiles accounted for more than a quarter of the world’s textile trade by the end of the seventeenth century (Das 2002). Despite the targeted destruction of the sector under British colonial rule, Indian artisans persevered. As of 2020, approximately 3.1 million households are engaged in weaving or allied activities (Ministry of Textiles, 2019).

In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, weaving is often a family enterprise, with multiple family members employed in the household-run business. In this article, we share insights from our recent mixed-methods study (Hammaker et al. 2023). The key takeaways about the workings of family-owned weaving businesses help us understand their economic or commercial productivity when multiple or single generations are involved. We also assessed the distribution of gains within the household, and the relationship between family governance, weaving productivity and women’s agency – and the data shows revealing trends.

Changing dynamics of family-owned weaving businesses

Participation in an intergenerational family business can influence household productivity in several ways. It enhances business productivity, household welfare and long-term sustainability due to the gains from the transfer of traditional knowledge and techniques across generations. It also provides incentives to sustain the business for future generations.

At the same time, family values or interpersonal conflicts could impede innovation, while nepotism may result in inefficient allocation of resources. Additionally, competing opportunities may even discourage future generations of potential weavers from participating in the craft. For example, from our field interviews, we found that younger respondents, particularly women, are likely to pursue higher education instead of weaving, as that could lead to higher-paying jobs. These respondents also expressed interest in migrating to larger cities for work.

The evidence on the relationship between women’s participation in family-owned businesses and their autonomy and decision-making power is similarly mixed. Historically, gender norms dictate that men lead household decision-making and serve as financial providers, while women are assigned supporting tasks (Econstra Business Consultants LLP, 2023). These stereotypical gender norms may prevent women from contributing to decision-making, even in households where they are actively engaged in family businesses. However, participation in family businesses can offer women a sense of ownership that could enhance their autonomy and confidence (Faraudello and Songini 2018).

Intergenerational weaving households in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana

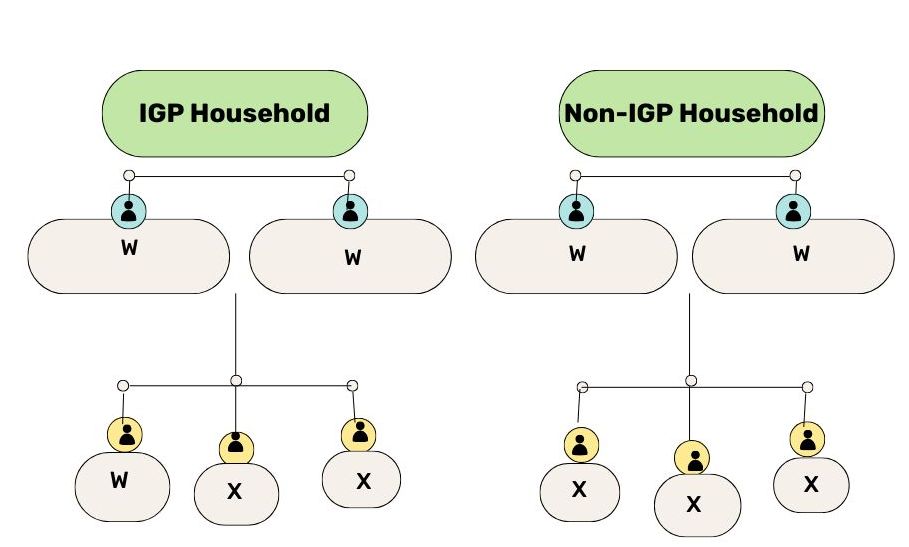

Using survey data of weavers in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, we compared productivity between households where multiple generations (such as parents and children who co-reside) participate in the family business and those where children of weaver(s) do not participate. We refer to households with multiple generations of weavers who co-reside as Intergenerational Participation (IGP) households, and households without multiple generations of related weavers as non-IGP households (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Composition of weaving enterprises

Our analysis of data from over 1,800 households – 371 IGP households and 1,514 non-IGP households – across five districts of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh shows that in 53% and 82% of households respectively, at least one woman and man report weaving as their primary activity. Generally, both the household head and their spouse engage in weaving. There were some observable differences in household characteristics, including the age and education of the household head, but the analysis accounts for these differences in its empirical model.

How family businesses impact weaver households’ productivity

The analysis uses a fixed-effects regression model to estimate differences in household productivity and women’s empowerment among IGP and non-IGP weaving households. The village fixed-effects control for any unobservable differences across villages that jointly determine household outcomes and IGP status within a household. It also includes an additional set of controls, such as the household head’s sex, education level, age group, whether the household belongs to other backward classes, and the house’s construction type, to account for the observable differences between IGP and non-IGP households.1

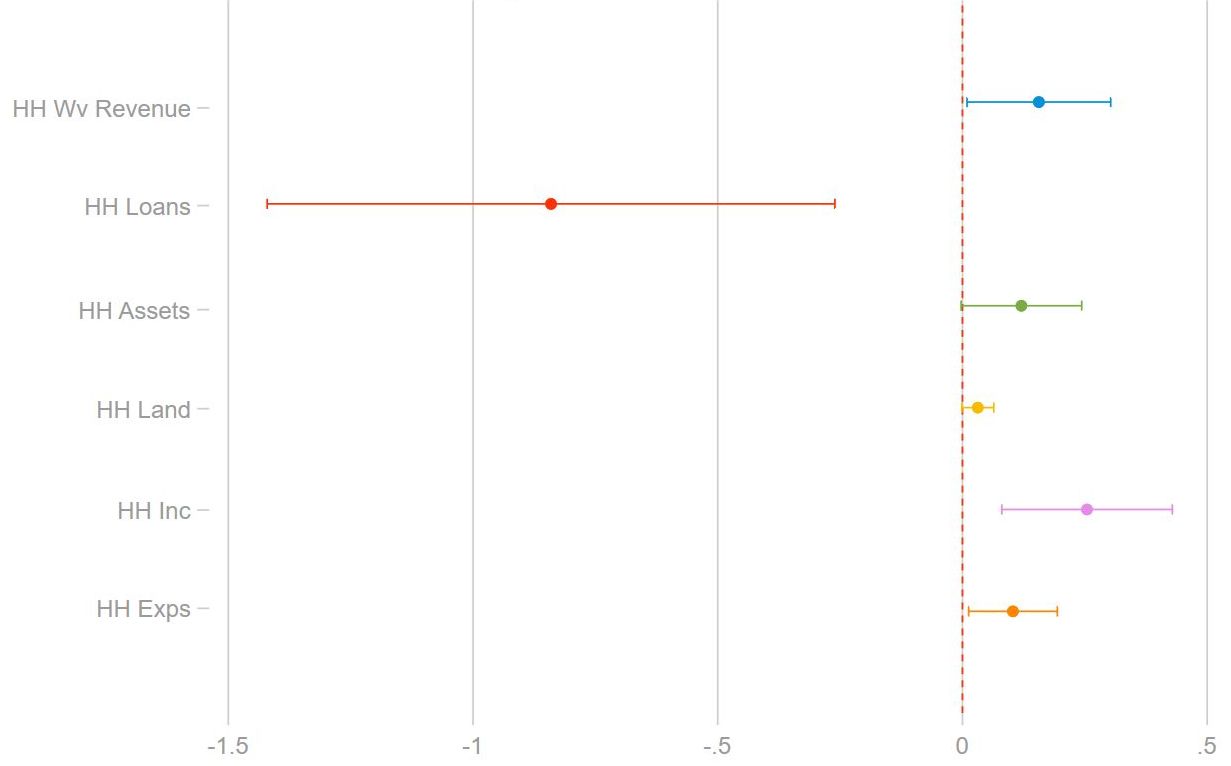

The analysis finds that IGP households with multiple generations of weavers fared better than non-IGP households in most measures of household productivity (Figure 2). Notably, IGP households earn 29% more in income and 17% more in weaving revenue compared with non-IGP households. They also owe 84% less to creditors in loans, own 12% more in (quartiles of) household assets, own 3.1% more land, and generate 10% more in expenses.

Figure 2. Household productivity outcomes, for IGP and non-IGP

Note: The measures of household productivity include natural logs of revenue from weaving enterprises, loans, income and expenses. We also include quartiles of number of household assets and an indicator for whether a household owns lands as measures of productivity. The caps represent 95% confidence intervals.

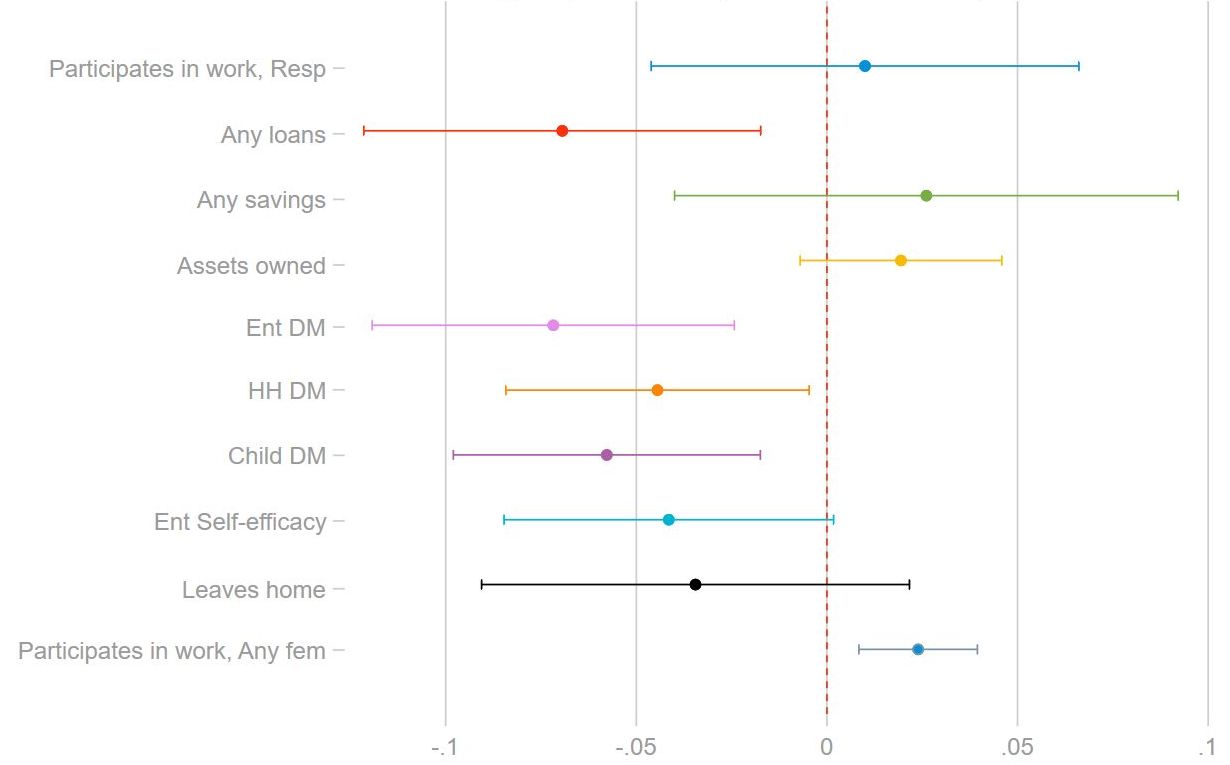

While IGP households exhibit greater productivity as a whole, there are no gains for women in terms of greater autonomy from participating in intergenerational family businesses (Figure 3). The results suggest that even though IGP households exhibit higher productivity outcomes, women in these households were worse off in metrics of agency, which included self-efficacy, autonomy to contribute to household decisions and control over household assets such as loans or savings.

Relative to non-IGP households, IGP households are 2% more likely to have at least one woman who participates in productive activities such as agriculture, salaried work, or casual labour). However, women from IGP households are 7% less likely to have household loans, are not more likely to have any savings, do not own more assets, contribute to 7% fewer enterprise decisions, contribute to 4% fewer household decisions, and contribute to 5% fewer decisions about child-rearing. They also report low confidence in enterprise-related self-efficacy, and are less likely to leave their homes weekly.

Figure 3. Women’s agency outcomes, for IGP and non-IGP

Note: To measure women’s economic empowerment outcomes, we use indicators for whether the woman has engaged in any paid work, has taken a loan, has any savings for personal use, or if the household has at least one female who participates in income generating activities. We also include proportion of household assets owned by the woman as an indicator for women’s economic empowerment. For women’s autonomy-related outcomes, we focus on decisions she can participate in solely or jointly, self-efficacy questions answered in the affirmative, and indicator for whether the woman leaves home at least once a week. The caps represent 95% confidence intervals.

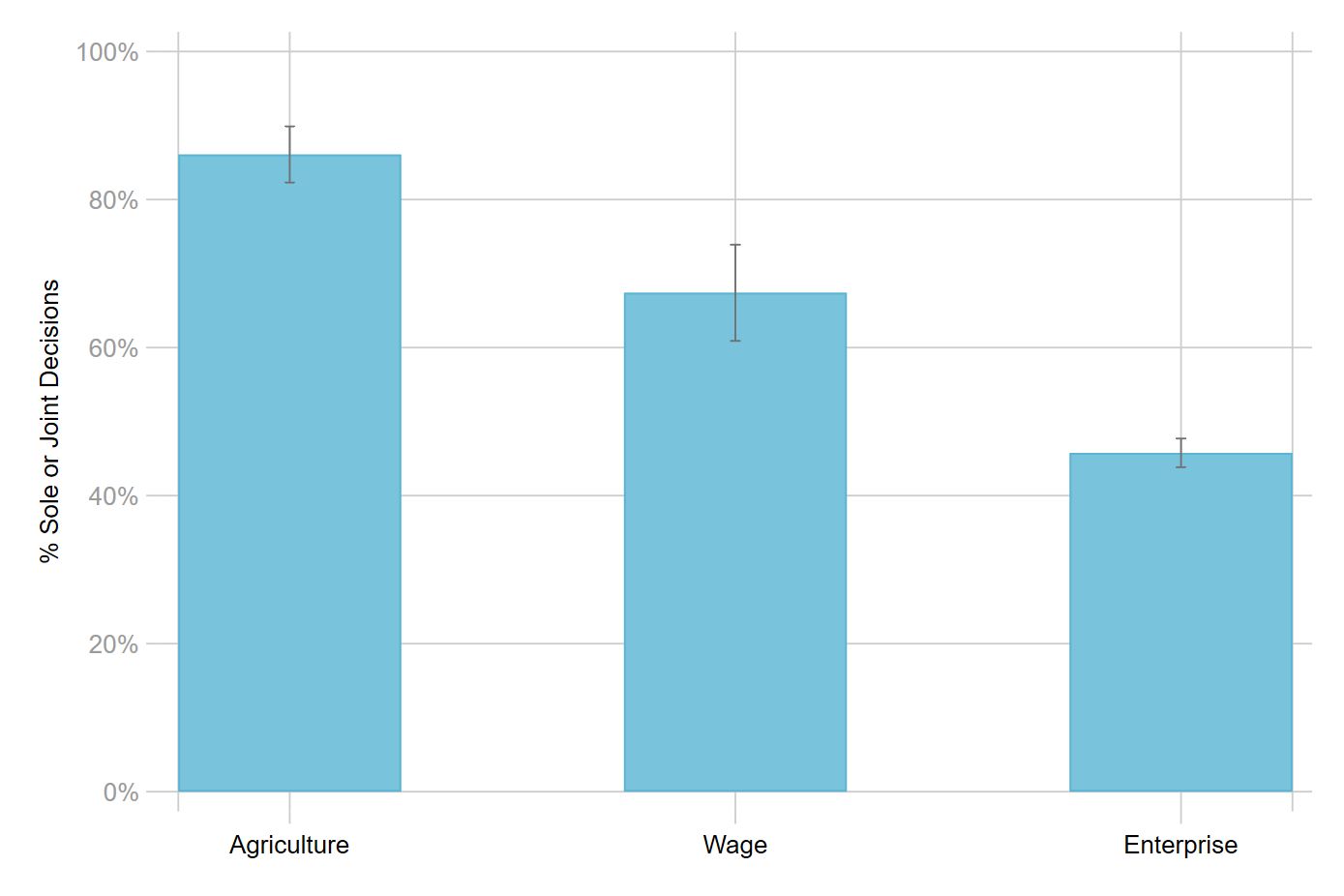

More generally women in our sample are also relatively less likely to contribute to household enterprise decisions, relative to other types of household decisions in cultivation or wage participation (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Women’s decision-making, by type of decision

Note: The bars represent the percentage of women in our analysis sample who make cultivation, wage participation, and enterprise related decisions either solely or jointly.

Implications and conclusions

Our analysis shows that weaving businesses with the participation of multiple generations are generally more productive in terms of household welfare measures such as revenue from enterprises, wealth and consumption expenditures. However, the distribution of these benefits are gendered, and women who work in multi-generational weaving businesses report lower self-efficacy and autonomy.

This finding may have tangible financial implications for the future of handloom weaving as a family business. The potential exclusion of women and girls from decision-making could create inefficiency for weaving enterprises, as these potential employees may consider opportunities to earn outside of their homes.

Based on our findings, practitioners working to mobilise weavers should consider and prioritise training to equip women to participate in family business decisions, and implementing behaviour-change interventions to encourage joint decision-making in the business.

Future research could also explore the causal relationship between family governance structures and productivity or women’s agency, to inform policies that incentivise participation in family weaving businesses. It could also study power dynamics within families to identify opportunities to design new interventions and prioritise equity, and use systems mapping of the weaving value chain stakeholders to identify areas for joint decision-making.

This article is based on findings from ‘Intergenerational Participation in Household Weaving Businesses and Productivity: A Case-study from Chitrika’ (Hammaker, Jain, Jain, Pandey and Patel 2023). This working paper is a part of the Swashakt Evidence Program, administered by 3ie and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Note:

- Results should be interpreted with caution: While we use a rich set of controls in our regression analysis, we are unable to control for endogenous selection, skills, motivation, etc., through an experimental or quasi-experimental strategy. Our study is descriptive and should not be used to make causal inferences about the relationship between intergenerational participation and household productivity or women’s agency.

Further Reading

- Crill, R (2015), The Fabric of India, Harry N. Abrams.

- Das, G (2002), ‘If We Were Once Rich, Why Are We Now Poor?’, In India Unbound: From Independence to the Global Information Age, Penguin Books. Available here.

- Ministry of Textiles (2019), ‘Fourth All India Handloom Census 2019-20’, Office of The Development Commissioner for Handlooms, Ministry of Textiles.

- Econstra Business Consultants LLP (2023), ‘The Role of Women in Indian Family-Owned Businesses: A Changing Landscape’, Article, 29 August.

- Faraudello, Alessandra and Lucrezia Songini (2018), “Women’s Role in Family Business: Evolution and Evidences from a European Case Study”, Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 14(2): 70-89. Available here.

01 February, 2024

01 February, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.