In the last few decades, tax credits have been introduced in many developing countries to incentivise investment in research and development (R&D). Looking at the staggered introduction of R&D tax credits across industries, this study finds that increases in tax credits were effective in increasing R&D expenditure, while leading to a decline in prices. This decline is primarily driven by a decline in markup, conditional on cost, as opposed to the passthrough of cost savings to prices.

“Most economists believe that innovation and competition are deeply intertwined, and for many the relationship is so close that it borders on tautology. In practice, many discussions of this relationship concentrate on possible causal links which run from competition to innovation. [...] Arguments which suggest that innovation drives competition in markets are less often made, and they have never been articulated quite as clearly as those stressing the effects of competition on innovation.”

-- Paul A. Geroski (1999)

Many governments use research and development (R&D) tax credits to incentivise private investment in R&D. Several empirical studies have examined the direct effect of these tax credits and found them to be effective in increasing the R&D expenditures and productivity of eligible firms (Chen et al. 2021, Dechezleprêtre et al. 2023). However, relatively less explored is the possibility that these policies may have competitive spillover effects on product market rivals, forcing them to reduce their prices by lowering their price-cost margins and investing in productivity improvements. Quantifying these effects can shed light on the mechanisms driving the impact of R&D on aggregate output and prices, and improve our understanding of how the gains from innovation are shared between producers and consumers. However, tracing the direct and spillover impact of an exogenous shock to the cost of R&D and its transmission to prices within industries has proven elusive.

Further, the empirical evidence on the effectiveness of R&D tax credits comes overwhelmingly from developed economies. Many large developing economies, including Brazil, China, and India, have introduced R&D tax credits in the last few decades. However, whether these policies are effective in developing countries with weak protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights (IPR) is unclear. Weak IPR regimes can limit firms' ability to realise the returns from their R&D investments, reducing their responsiveness to tax incentives. On the other hand, tax credits may ease financial constraints for innovative firms in countries with underdeveloped financial institutions, increasing their responsiveness to tax credits.

In a recent paper (Jain and Singh 2023), we provide novel empirical evidence on these issues by exploiting variations in the cost of R&D across industries due to the staggered introduction of an R&D tax credit scheme in India.

India’s R&D tax credit scheme

The Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR), under the Ministry of Science and Technology, is responsible for the recognition of in-house R&D units within firms. Prior to 1998, firms with registered in-house R&D units were eligible for a 100% tax deduction on the qualifying current and capital R&D expenditures. There was a change in the policy, with the R&D tax credits available to eligible firms increasing from 100% to 125% in 1998, and eventually to 150% in 2001. This was introduced in several industries in 1998, namely drugs, pharmaceuticals, electronic equipment, computers, telecommunication equipment, and chemicals. It was extended to the helicopters and aircraft sector in 2001, and to the automobile sector in 2004. The firms with registered in-house R&D units in the rest of the industries were unaffected by the reform and continued to be eligible for 100% tax deductions on R&D spending. Additionally, the reform partitioned firms based on a clearly defined eligibility criterion1 – creating a set of ineligible firms not directly impacted by the reform – enabling us to recover the spillover effects within industries.

Data and empirical strategy

We combine the policy variation with data from firms' financial statements and detailed firm-product level information on physical quantities and sales for 1992-2007. These data come from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s Prowess database, a panel of medium and large-sized firms that account for a large share of formal manufacturing output and taxes. We observe the two key outcome variables: firm-level R&D expenses and firm-product level prices. Further, to disentangle the mechanisms driving the overall effect on prices, we closely follow the methodology proposed by De Loecker et al. (2016)2 to estimate the underlying component of prices (that is, marginal costs and markup).

We estimate the causal effect of the tax credits using a difference-in-differences framework by comparing outcomes for firms in treated industries to those in the control industries before and after the policy change.

Effect of the policy on R&D expenditure and prices

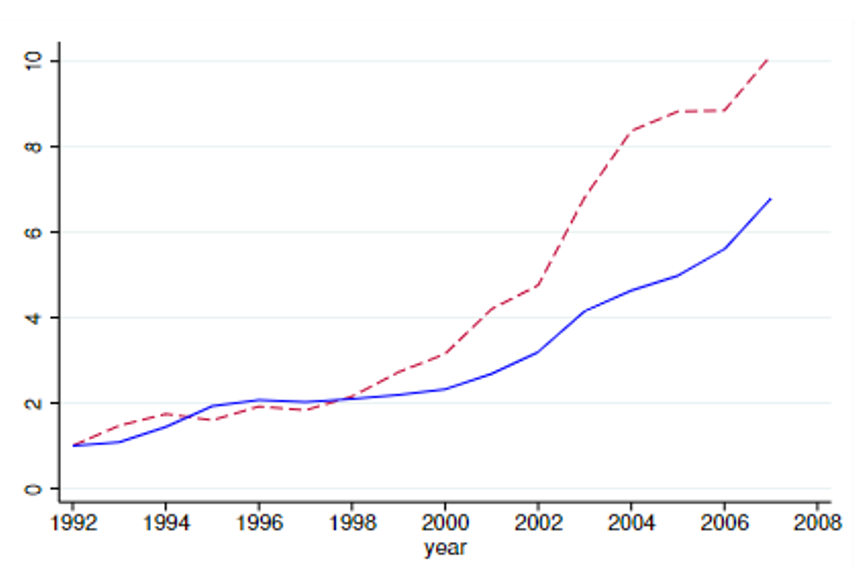

Figure 1 plots the trends in aggregate R&D expenditure of industries treated in 1998 and the never-treated industries, normalised to the initial year. The figure provides strong visual evidence of a trend break after the introduction of the tax credit scheme in 1998. While there is little difference in the increase in the aggregate R&D expenditure for the treated and the never treated industries in the five years leading up to the reform, there is a large increase in the R&D expenditure for treated industries relative to the never treated group post the introduction of the tax scheme.

Figure 1. Aggregate R&D expenditure (1992-2007)

Note: The dotted red line indicates R&D expenditure for treated industries; the solid blue line indicates expenditure for non-treated industries.

We find that the policy has a large positive impact on R&D spending – our results imply that firms in treated industries, on average, increase their R&D spending by 60% in response to the increase in tax credits. Further, to separate the direct effect of the policy on the eligible firms from any spillover effects on the ineligible firms, we test for the differential effect of the policy within industries based on eligibility status of the firms. Our results imply that the increase in the R&D expenditures is almost entirely driven by the eligible firms. We find no significant impact on the R&D expenditures of ineligible firms, suggesting a lack of substantial spillover effects of the policy on firm-level R&D.

To better understand the mechanisms driving the responsiveness to the tax credits, we test for heterogeneity based on firm and industry-level measures of financial constraints. Financial constraints may be particularly binding for innovating firms in India, given the underdeveloped banking sector and equity markets, and could make firms more responsive to tax credits. The effect of the policy on R&D spending is indeed stronger for young firms and firms in industries with greater reliance on external finance.

Our results also suggest that the policy leads to a decline in firm-product level prices by 18%, on average. Further, prices reduced significantly for both eligible and ineligible firms, by 16% and 19% respectively. These findings provide some of the first causal evidence of the impact of R&D tax credits on prices and confirm the presence of strong competitive spillover effects on the firm-product level prices for ineligible firms.

Effect on marginal costs and markup

To better understand the mechanisms underlying the price decline, we explore the policy's impact on firm-product level marginal costs and markup. The reform leads to a significant decline in marginal costs by around 18%, on average. Further, the decline in marginal costs for eligible firms suggests that they invested primarily in improving their productivity. A heterogeneity analysis suggests that eligible firms reduce their costs by 23%; however, ineligible firms also reduced their costs by 14%, suggesting that the policy has positive spillovers on the productivity of ineligible firms.

Prices can also decline due to changes in markup, conditional on costs. Our results imply that the policy lowers markup, conditional on marginal costs, by 13% on average. Further, this effect is particularly strong for ineligible firms, whose markup declined by around 16% due to changes in demand. The effect is attenuated somewhat for eligible firms, who experience a decline in markup by around 10%. These results confirm the presence of strong competitive spillovers on ineligible firms.

Comparing the average effects on prices, marginal costs, and markup (conditional on costs), we find that the downward pressure on markup accounts for almost three-fourths of the decline in prices, with the rest being accounted for by the incomplete passthrough of costs to prices. The cost-saving channel accounts for 40% of the decline in prices for eligible firms, while it is only 20% for ineligible firms.

Together, these results provide strong evidence that the tax credit policy leads to a considerable increase in competition between firms in the treated industries and that both the eligible and ineligible firms experience downward pressure on their markup due to demand-side changes.

Effect on output and factor inputs

Finally, we also examine the effect of the policy on firm output and factor inputs. The results imply that the policy increases firm sales by 17%, capital stock by 13%, and compensation to employees by 16%. Further, we find that these effects are primarily driven by eligible firms that experience an increase in sales by 33%, capital by 30%, and compensation by 30%. Interestingly, the effect on ineligible firms for all these outcomes is positive, but small in magnitude. Thus, although the policy leads to an increase in eligible firms' market share, ineligible firms are able to maintain their revenues at pre-reform levels.

Conclusion

Exploiting the staggered introduction of weighted tax credits for R&D spending across industries in India’s manufacturing sector, we find that R&D tax credits are effective in stimulating private R&D spending. Further, we provide causal evidence that the policy results in a relative decline in prices in the industries targeted by the reform. The price decline is observed for both eligible and ineligible firms and is primarily driven by a decline in markup, conditional on cost, as opposed to the passthrough of cost savings to prices. Our results suggest that R&D tax credits can increase competition between firms within industries.

Notes:

- To be eligible for tax credits, firms have to register their in-house R&D units with the DSIR. The in-house R&D unit is required to provide its past three years of annual reports, information on past, present, and future research projects, details on the scientific personnel and equipment working in the R&D unit, and photographs of the R&D facility. The registration has to be renewed every few years (typically three years) and renewal is based on satisfactory performance of the unit.

- This method relies on the firm’s product-wise cost minimisation to get an expression for firm-product markup as a ratio of the output elasticity with respect to a variable input and the input’s expenditure share in total revenue. The main advantages of this method are that: (i) it allows for multi-product firms; (ii) estimates a quantity-based production function; and (iii) accounts for unobserved input allocations across products and unobserved heterogeneity in firm level input prices.

Further Reading

- Chen, Zhao, Zhikuo Liu, Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato and Daniel Yi Xu (2021), “Notching R&D Investment with Corporate Income Tax Cuts in China”, American Economic Review, 111(7): 2065-2100.

- Dechezleprêtre, Antoine, Elias Einiö, Ralf Martin, Kieu-Trang Nguyen and John Van Reenen (2023),“Do Tax Incentives Increase Firm Innovation? An RD Design for R&D, Patents, and Spillovers”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 15(4): 486-521.

- De Loecker, Jan, Pinelopi K Goldberg, Amit K Khandelwal and Nina Pavcnik (2016), “Prices, Markups, and Trade Reform”, Econometrica, 84(2): 445-510.

- Geroski, PA (1999), ‘Innovation as an Engine of Competition’, in DC Mueller, A Haid and J Weigand (eds), Competition, Efficiency, and Welfare: Essays in Honor of Manfred Neumann.

- Jain, T and R Singh (2023), ‘R&D Tax Credits and Price Competition: Evidence from India’, Working Paper.

05 February, 2024

05 February, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.