Launched in 2014, the ‘Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram’ seeks to improve menstrual hygiene in India by addressing issues around affordability as well as awareness. In this post, Kanika Dua contends that the programme – combined with enhanced provision of sanitation facilities – helped increase the adoption of hygienic menstrual management products, particularly among rural, less educated, and economically disadvantaged women.

Amartya Sen described development as a process of expanding human freedom, which includes economic freedom, political freedom, social opportunities, transparency, and security (Sen 1999). One of the undeniable obstacles curtailing the freedom of women is the monthly menstrual cycle that limits their movement and, compounded by entrenched social taboos associated with menstruation, adds to their physical and emotional toll and hampers their productivity. Fortunately, the availability of menstrual hygiene products has been a transformative force, enabling women to regain their mobility during their menstrual cycles and safeguard their health by reducing the risk of infections. However, despite the prevalence of menstrual hygiene products, their universal adoption remains encumbered by a multitude of factors. These encompass lack of affordability, limited awareness, and inadequate sanitation facilities for changing and cleaning.

Policy interventions in India

In recent years, the central government adopted a holistic and multi-pronged strategy to improve menstrual hygiene. A pivotal component of this strategy is the national adolescent health initiative known as the Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK), launched in January 2014. The RKSK has played a crucial role in accentuating the importance of providing information, support, and access to menstrual health management products through the establishment of Adolescent Friendly Health Clinics and the deployment of trained counsellors. Additionally, the Swachh Bharat Mission (a Centre-led initiative for clean India) has focused on creating sanitation infrastructure such as community toilets and personal toilets, and the promotion of behavioural change, which includes raising awareness about hygienic practices.

Trends in menstrual hygiene during 2015-2019

I conduct an empirical analysis using data from the National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) to assess whether these recent efforts have led to a positive change in the adoption of clean hygiene menstrual practices among women in India. For this study, I aggregate data from two rounds of the survey conducted in 2015 (NFHS-IV) and 2019 (NFHS-V).

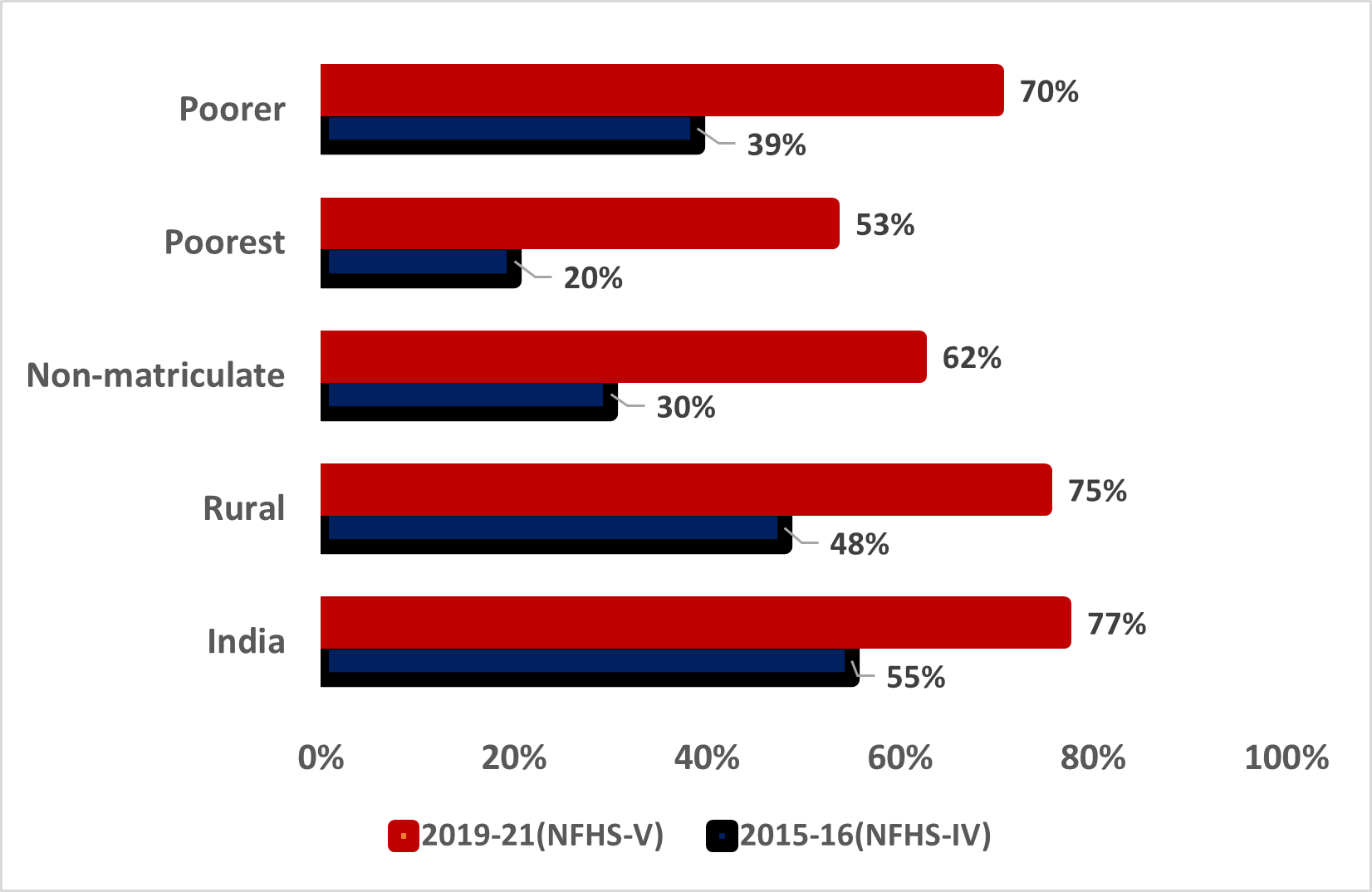

Aggregate trends (shown in Figure 1) reveal a noteworthy transformation: In 2015, just 55% of the surveyed women were reported to use hygienic menstrual management products such as locally made sanitary pads, sanitary napkins, tampons, or menstrual cups. However, by 2019, this figure surged to an impressive 77%. Even more striking is the granular data, which underscores that the most substantial improvement took place among rural, less educated women hailing from the most economically disadvantaged sections of society.

Figure 1. Trends in usage of menstrual hygiene products

Three main trends prevail: First, the data highlights that the most significant progress in menstrual hygiene management (MHM) has been observed in rural districts, where a lack of information had hitherto hindered the widespread use of hygienic menstrual products. In 2015, less than half of rural women reported using clean menstrual hygiene products. However, by 2019, approximately three-fourths of women from rural areas reported using such products.

Second, the progress in the adoption of MHM products has been particularly pronounced among women with lower levels of education. These women often possess limited autonomy and access to resources, which impedes their access to clean menstrual hygiene products. In 2015-16, only three in 10 women without a matriculation qualification were reported to use such products. However, by 2019-21, this figure had doubled, with more than six in 10 women reporting the use of clean menstrual hygiene products.

Third, the assertion that the scheme has benefitted the neediest can also be seen if we analyse the changing pattern of menstrual hygiene products among the women in different wealth categories. The NFHS employs a wealth-based categorisation, distinguishing households into five distinct economic categories: the poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and the richest. A comparative analysis of NFHS data spanning rounds IV and V reveals that the use of menstrual hygiene products has increased most substantially in households from the poorest and poorer wealth quintiles.

In 2015, the landscape was bleak: only around 20% of women in the poorest category used hygienic menstrual health products. However, the NFHS-V data paints a different picture; by 2019, a significant number of women (53%) in the poorest category had embraced menstrual health products. A similar narrative unfolds for women from the poorer class. In 2015, just 39% of women in the poorer wealth quintile had access to clean menstrual health products. Remarkably, by 2019, more than 70% of women from these households had adopted clean menstrual health products.

Concluding thoughts

While discussing schemes related to women empowerment or sanitation, menstrual health is one of the most ignored and less often spoken about aspects. However, menstruation indeed places restrictions on women's freedom of movement, freedom of work and to some extent freedom of expression. This increased use of clean menstrual hygiene products is a positive change. The multi-pronged approach of SBM and RKSK which, on one hand, focusses on building physical hygiene infrastructure (such as toilets and sanitary pad vending machines), has also - instigated behavioural change by raising awareness among adolescent girls on importance of using clean menstrual hygiene products – thereby helping address unmet needs at an unprecedented pace.

Views expressed are personal and do not represent any authority/ institution.

Further Reading

- Sen, A (1999), Development as Freedom, Alfred Knopf, New York.

01 April, 2024

01 April, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.