In light of the changing healthcare burden for women, with a rise in mortality due to non-communicable diseases, Bhan and Shukla outline the incidence of diseases in Indian states over the last two decades, and the role that the PMJAY programme plays to alleviate constraints to healthcare access. They note the male bias in utilisation of public-funded healthcare programmes, as evidenced from state insurance schemes, and highlight the need to understand the barriers to access and user experience of women.

In September 2023, India’s national health insurance programme, the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY), completed five years since its launch. This marks an important moment to reflect on the experience of PMJAY– one of the world’s largest public-funded health insurance programmes, and one that is now becoming a mainstay of the national health policy discourse and considered to be the route towards universal health coverage. PMJAY facilitates health access for poorer households, even as states vary in their criteria for eligibility of beneficiaries – from targeted to universal – and this has become an important flashpoint for the future of its implementation. It provides coverage of up to Rs. 500,000 for the family, is open to all members irrespective of gender and age, and can be utilised in empanelled secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities. This also includes private healthcare facilities along with public facilities.

The changing healthcare burden for women

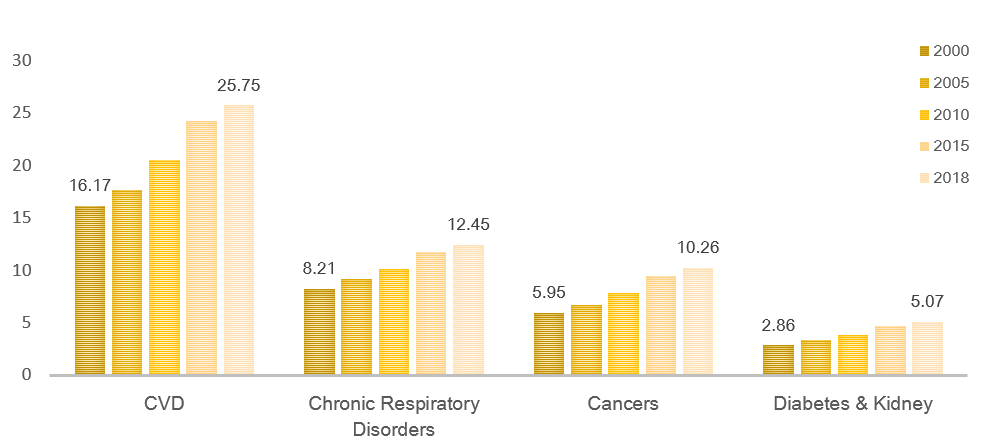

The establishment of the PMJAY has coincided with an important inflection point for women’s health in India. Healthcare access for women in India predominantly focused on the provision of maternal and childcare services, to address high maternal, neonatal and infant mortality rates. With the decline of these rates, and with the epidemiological transition from infectious to non-communicable diseases (NCDs), this picture is changing, globally as well as in India, and points to the changing healthcare needs of women (see Figure 1). As per data from the India State Level Burden of Disease (2017), non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), chronic respiratory conditions, cancers, diabetes and kidney-related health issues accounted for 1 in 2 (53.5%) deaths among women in 2018, compared to 1 in 3 (33%) in 2000.

Figure 1. Mortality from non-communicable diseases among women in India

Note: The graphs depict the mortality from non-communicable diseases as a proportion of the total mortality among women in that year.

Source: Indian Council of Medical Research, Public Health Foundation of India, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, GBD India Compare Data Visualization (2017).

Further unpacking this classification by specific health conditions shows that CVDs (coronary heart diseases, stroke, and cardiomyopathies) in 2018 accounted for 1 in 4 (25.7%) deaths among women in India. CVDs accounted for the highest mortality in Punjab, Kerala, West Bengal and Goa in 2018. However, in terms of change, since 2000, states that showed the steepest growth in CVD mortality included Punjab, Telangana and Maharastra. In Punjab, incidence of CVDs in women increased substantially from 29% to 41%. In Telangana deaths due to CVD rose notably from 19% to 30%, whereas in Maharashtra they escalated from 21% to 32%.

Chronic respiratory conditions (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, occupational lung diseases and pulmonary hypertension) followed CVDs as the leading cause of deaths, with mortality rising from 8.1% in 2000 to 12.4% in 2018 – an increase of 50%). Mortality among women from chronic respiratory conditions increased from 13% to 19% in Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Jammu-Kashmir and Ladakh, potentially linked to the use of chulhas or wood-fire for cooking, which is associated with women’s domestic work and disproportionately affects their health.

In the north-eastern states, between 2000 and 2018, cancer related mortality rose among women from 13.3% to 20.2% in Mizoram, 8.7% to 15.2% in Sikkim and 8.1% to 14.2% in Meghalaya, with the highest fatality attributed to breast and cervical cancers. Women dying from diabetes and kidney disorders also doubled in Tamil Nadu, Goa, Punjab and Kerala, from 6.3% to 12% between 2000 and 2018. Morbidity from these conditions can also be lifelong and irreversible, significantly impacting the quality of life and household out-of-pocket spending. These trends in NCDs signal the need for urgent attention to women’s health needs and understanding their determinants across state contexts.

Gendered barriers to healthcare utilisation

The health needs of women have often been understood using the ‘three delays framework’ (Thaddeus and Maine 1994), as in the case of maternal health. The three delays include: i) delays in seeking care due to lack of recognition and prioritisation of women’s health needs within households; ii) delays in reaching an adequate health facility due to limited or low-quality health services and healthcare providers who can ensure timely identification of risks and vulnerabilities related to NCDs, and iii) delays in receiving affordable care due to financial constraints experienced while seeking specialty services.

India’s public funded health insurance programmes can address the third delay, and improve affordability and risk protection for millions of women at the national and state levels. Available data on enrolment for the PMJAY are encouraging and demonstrate progressive strides towards equivalent rates of women and men enlisting to avail health services. But gender disparities in accessing and using insurance are not fully understood, and evidence from state insurance schemes indicates a pro-male bias in use. This bias has been noted in the frequency of use of healthcare in terms of visits and spending in Rajasthan (Dupas and Jain 2021), as well as based on expenditure on hospitalisation in Andhra Pradesh (Shaikh et al. 2018). This gender bias exists because of women’s limited agency for health-seeking in the household and their reliance on men for transportation and support; the sanction needed from family members to access healthcare; and the tendency to neglect women’s health needs when additional expenses related to diagnostics and medicines pile up. Further, the complexity of using insurance programmes and navigating/negotiating healthcare access further deter women from seeking care, and present challenges such as decision-making on treatments, negotiating with insurance agents, and the lack of support during waiting times for treatment. A gendered understanding of health insurance access and subsequent health-seeking is required to understand these gaps.

The way ahead

So, what might the next phase of public-funded insurance bring, specifically with an eye to addressing a few of these challenges? Firstly, we urgently need to understand the user experience of public-funded programmes by gender, in particular the barriers to utilise it, and patient-centeredness in health care interactions. Learnings from maternal as well as sexual and reproductive health research (such as Diamond-Smith et al. 2018, Srivastava et al. 2018) have shown the importance of respectful care and patient-centered practices in women’s health seeking, and this can be a game-changer when setting up protocols for NCD risk assessment for women (for example, in reproductive cancer screenings).

Secondly, even as more and more hospitals get empanelled into publicly funded programmes, we need to understand how healthcare quality and practices affect women’s health use. Are women accessing healthcare more freely if they are buffered by health insurance? What implementation aspects need to be considered as we design more gender friendly and responsive health policies and programmes? Literature from other contexts has shown that families are less likely to use health insurance for women if the additional uninsured costs from diagnostics and medicines are high (Karpagam et al. 2016, RamPrakash and Lingam 2021). The dynamics of health utilisation and women’s willingness to forgo the healthcare they need has not been understood well, and may relate to both their lack of self-awareness as well as low self-value.

Finally, women’s empowerment needs to be considered central to programme planning for tackling NCDs, with the programmes enhancing values of self-care so that women are encouraged to seek and demand that their health needs be prioritised within families and within health systems.

Further Reading

- Diamond-Smith, Nadia, Ruby Warnock and May Sudhinaraset (2018), “Interventions to improve the person-centered quality of family planning services: a narrative review”, Reproductive Health, 15(144).

- Dupas, P and R Jain (2021), ‘Women Left Behind: Gender Disparities in Utilization of Government Health Insurance in India’, NBER Working Paper 28972. This paper has been abridged for Ideas for India here.

- Karpagam, Sylvia, Akhila Vasan and Vijaykumar Seethappa (2016), “Falling Through the Gaps: Women Accessing Care under Health Insurance Schemes in Karnataka”, Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 23(1).

- Ram Prakash, Rajalaskhmi and Lakshmi Lingam (2021), “Why is women’s utilization of a publicly funded health insurance low?: a qualitative study in Tamil Nadu, India”, BMC Public Health, 21(350).

- Shaikh, Maaz, Sanne AE Peters, Mark Woodward, Robyn Norton and Vivekanand Jha (2018), “Sex differences in utilisation of hospital care in a state-sponsored health insurance programme providing access to free services in South India”, BMJ Global Health, 3(3).

- Srivastava, Aradhana, Devaki Singh, Dominic Montagu and Sanghita Bhattacharyya (2018), “Putting women at the center: a review of Indian policy to address person-centered care in maternal and newborn health, family planning and abortion”, BMC Public Health, 18(2).

- Thaddeus, Sereen and Deborah Maine (1994), “Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context”, Social Science & Medicine, 38(8): 1091-1110.

22 December, 2023

22 December, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.