The Union Budget presented earlier this month was the last full-year budget before next year's general elections. Rajat Kathuria looks back to India's economic performance in 2014 and suggests that this year’s budget comes against a similar backdrop, with India once again seeing healthy growth projections. He touches upon the budget's focus on macroeconomic fundamentals, including rationalizing untargeted subsidies and replacing them with capex, and lauds as a step towards ensuring effective fiscal consolidation and increased investment in public infrastructure.

“In the 75th year of our Independence,” said the Honourable Finance Minister during her presentation of the Union Budget for FY2023-24, “the world acknowledges India as a bright star.” Our expected real gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 7% in FY2022-23 supports the optimism – and it seems defensible for the coming year as well, albeit with a lower growth expectation of 6%. Optimism, naturally, doesn’t occur in a vacuum, but is based on what is happening in other major economies. Growth rates across the world have declined, and international institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have adjusted these downwards in recent times. The successive downward revisions reflect the growing uncertainty in the global economy. The World Bank has projected a sharp slowdown in global growth from 2.9% in 2022 and to 1.7% in 2023, with advanced economies projected to grow by only 0.5% in 2023, much lower than the growth rate of 2.5% in 2022. In comparison, India’s growth projections look healthy, due in part to the prevailing recessionary outlook for the advanced and developed markets.

History repeating itself

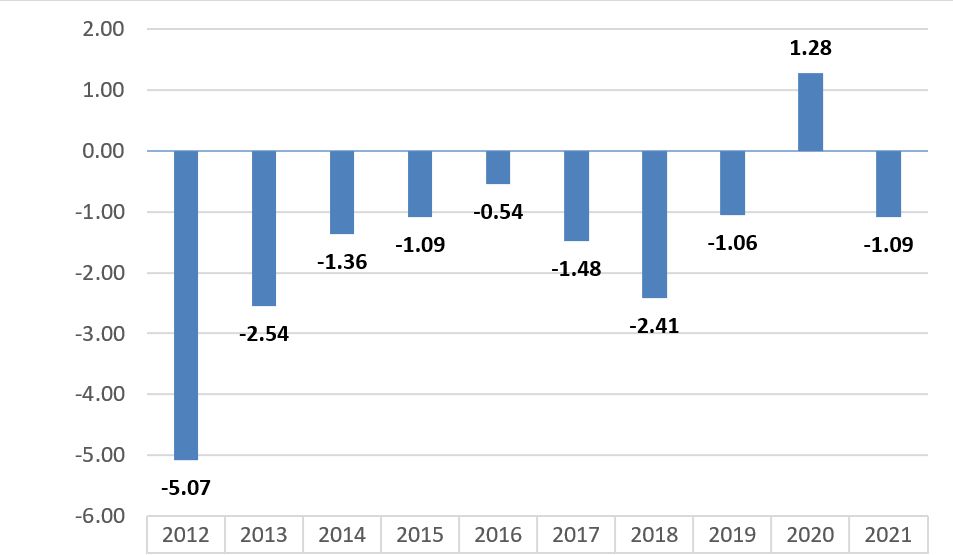

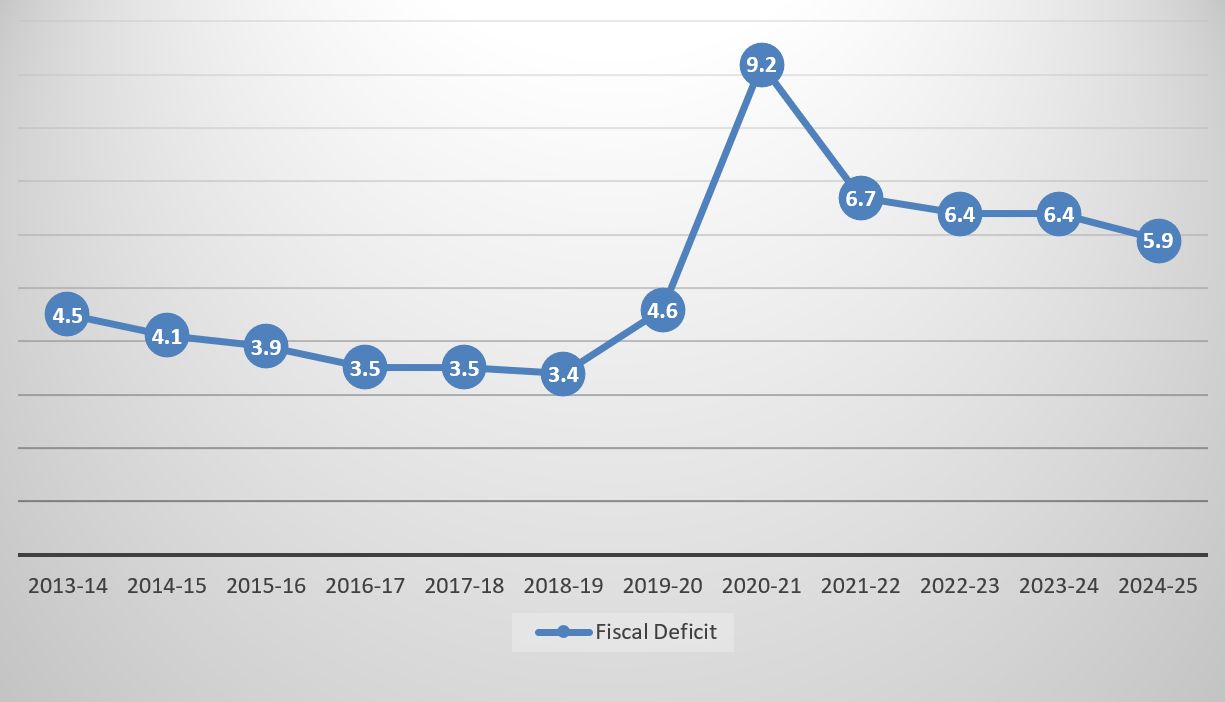

Truth be told, we have been here before. In 2014, when the new government came to power with a decisive mandate, the world faced an economic slump, tumbling crude markets and falling prices. Economists agreed then that India was a rare ‘bright spot’ among emerging markets. The fall in commodity prices hurt raw-material exporters such as Brazil, Russia and South Africa, but were a boon for India, which still imports three-fourths of the oil it consumes. While rich economies agonised over falling commodity prices, we were delighted to pay less for energy. The ‘sweet spot’ of low current account and fiscal deficits (see Figures 1 and 2), high growth and declining inflation augured well for the country.

Figure 1. Current account balance, as a percentage of GDP, from 2012-2021

Figure 2. Fiscal deficit as a percentage of GDP, from 2013-14 to 2024-25 (projected)

Rather than a one-time ‘big bang’ reform that produces political hurdles and widespread resistance in entrenched democracies like ours, the consensus was that the political mandate in 2014 provided an opportunity for “persistent, encompassing, and creative incrementalism” (Government of India, 2015) that could, ultimately result in lasting reform. While the external environment was inert, the challenges in other major economies made India the favourite of eager investors. If India focusses on fixing domestic structural and implementation bottlenecks, the prevailing narrative proclaimed that the bite of adverse global conditions could be less painful due to the vast potential in India’s untapped domestic market.

The opportunity, like many that have come India’s way, was not fully exploited. Pithily, we “snatched failure from the jaws of victory” (Forbes 2022). Much needed structural reform for containing the revenue deficit, continuing public sector disinvestment, widening the tax base, simplifying tax administration, and above all making India a competitive destination to give wings to the ‘Make in India’ programme, faced familiar execution bottlenecks and some policy resistance. Second generation reforms remained elusive.

The fortune that smiled on India in 2014 inevitably vanished, and instead a series of shocks close on the heels of each other cast a shadow on India’s status as the jewel of emerging markets. Demonetisation in 2016, followed by the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime in 2017 and the brutal Covid-19 pandemic, all affected the economy in different ways. Demonetisation may have propelled the digital economy, but it had a deleterious impact on micro enterprises. GST added another blow for the smaller MSMEs, who were not financially or technically equipped to embrace the new tax regime. Covid-19 was the final nail in the coffin for MSMEs, who were most severely impacted and, like their bigger and more illustrious counterparts, wrestled with supply disruptions, adverse customer demand, rising costs, and declining profits, all without the benefit of deep pockets.

Precedent-shifting pre-election budget: An eye on strong macro fundamentals

Against this backdrop, fortune has once again smiled on India in 2023. India is once more the cynosure of overseas eyes and perhaps its own as well, with one significant difference – the global environment is no longer inert, but outright hostile, with growing protectionism and geopolitical churn. As the Finance Minister presented her last full-year budget on 1 February, an opportunity beckoned. India, the ‘bright star’, needed to exercise restraint on populist impulses on the eve of general elections. As the rest of the world – specifically G20 nations – watched the exercise unfold in Parliament, India needed to demonstrate its earnestness as the world’s largest democracy ready to assume leadership, especially among emerging markets. The latter of course is a process that will evolve over the next several years, if not decades, starting with the momentous G20 Presidency this year. On the populist urge, the Budget was not only restrained but remarkably so, the seeds for which had been sown some time ago. One could also argue that given the circumstances around the budget formulation exercise, the honourable Finance Minister had little choice but to do what she did; but that is neither graceful nor warranted – credit must be given where it is due.

The recognition that sustainable and inclusive growth requires strong macro fundamentals, although already well known, was formally institutionalised in India in 2003 with the passing of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act. The Act imposes fiscal discipline and financial accountability on the government, and although the original targets were modified in 2016, the principle that revenue deficit ought to be zero and fiscal deficit remain manageable at around 3% is alive and kicking. Whether we like it or not, international credit rating agencies discriminate in favour of western economies, giving them much more leeway for fiscal profligacy than they extend to the Global South.

Regardless of the pressure from subjective international institutions, we are finally putting our own house in order. Off balance sheet items worth thousands of crores have been moved into the budget, bringing responsible transparency into the accounting. A related macro signal that is palpable is that untargeted subsidies are sought to be rationalised and replaced by capex. The underlying message is strong – investment will beget efficiency and save costs that a blanket subsidy-based regime cannot. I remember several meetings in government where the clamour for subsidies grew loudest at the time of the budget, with the most connected and active gaining from the system, while poor farmers, landless labourers, and the micro unorganised/informal or Own Account Enterprises (OAE) in whose name all this was being pursued were hardly represented.

There has been a huge reduction in subsidies following the winding down of the Covid-19 free food scheme, accompanied by subsidy cuts on fertilisers. The resultant fiscal savings of 0.8% of GDP has allowed the government to reduce the fiscal deficit by 0.5% to 5.9% of GDP in the budget for FY2023-24, while also creating room for increase in other expenditure. The road for FRBM compliance appears to have been paved with good intent and hopefully there will not be any implementation roadblocks going ahead.

The pandemic also forced the government to increase expenditure on capex, as the private sector stayed away due to both demand and supply side weaknesses. It is no different in this year’s Budget. To crowd in unwilling private investment, the Finance Minister has proposed an increase in public investment in infrastructure amounting to 3.3% of GDP, that includes Rs. 10 trillion capex, and Rs 3.7 trillion grant-in-aid to states. This is a massive 33% jump from last year’s allocation, and is a necessary step for several reasons. Let me address why it should be viewed as means to an end.

Potential for further growth

India’s golden years of growth between 2004-08 were marked by massive doses of private investment, with total investment touching 38% of GDP in this period. Investment has since fallen to less than 30%, and both monetary and fiscal policy have been attempting to revive it, albeit in difficult circumstances. Monetary policy has focused on inflation in recent times, while fiscal policy has provided the needed stimulus. How long can the government continue to prop capex? It is not just the resources that matter, but the quality of the infrastructure that gets created.

A conspicuous absence from this year’s Budget speech was public private partnerships (PPP). Reviving the decade long decline in private investment in infrastructure is vital for productive job creation, and must be accompanied, as acknowledged by previous Finance Ministers (including the late Arun Jaitley and P Chidambaram, among others), by institutional and regulatory reform, including efficient dispute resolution processes for PPPs. They must be viewed as an instrument to not only ease capacity and financing constraints, but also as an effective tool to promote competition in service delivery and improve the quality of services. The government’s role in regulation could be the difference between good and sub-optimal outcomes. Recall that in 2014, the rallying cry in the budget speech was for “minimum government, maximum governance”. As we inch back to a similar situation, this should come back on the agenda. Meanwhile a push for sustained public investment in infrastructure in the short-term is defensible for much needed job creation and eventually to crowd-in private investment.

There is a sliver of hope – corporate balance sheets have improved recently, and credit growth has recovered. Supply side disruptions caused by the pandemic are also beginning to ease, but the real question is what it will take to get private investment back to the levels we achieved during the golden years. For that we perhaps need to wait a bit longer, since ‘shovel ready’ projects are necessary in the short run. Of all markets that have seen reform since 1991, the land market remains the least transparent and continues to impose constraints on setting up large projects with employment potential. Meanwhile the government needs to continue spending on infrastructure, along with improving the ease of doing business and all its ingredients! This especially applies to MSMEs that face disproportional handicaps – they were helped by the Emergency Credit Linked Guarantee Scheme (ECGLS) last year, and its extension is a welcome step.

Trade restrictions have proliferated globally in recent years, and India too has been guilty of protectionism. With the objective of import substitution and to give fillip to the ‘Make in India’ initiative, India had raised duties on several products across several sectors. Fortunately, this year’s budget eschewed this path, recognising that external competitiveness gets adversely affected by raising tariff walls. After all, import tariffs are nothing but an export tax, and therefore should no longer be part of our policy set (barring exceptions). Empirical evidence points unequivocally to the fact that no country becomes globally competitive by serving just the domestic market, and no country becomes an economic power without being globally competitive. Thus, the production linked incentive scheme that forms part of India’s new industrial policy is well designed, and must be accompanied by measures that overcome domestic handicaps such as those in the now familiar ‘Ease of Doing Business’ index. To shore up exports as the global economy weakens is a challenge made worse due to our own stubborn infrastructural and logistical bottlenecks. Creating barriers for others (in the form of customs duties) to surmount lack of domestic competitiveness is a recipe for failure and capture. However, if this budget is any indication, we are thankfully on the way to overcoming this routine in India. Competitiveness, by way of lowering tariff barriers, is also attractive for global value chain participation, as is apparent from the success story of attracting Apple and Samsung to India.

Concluding thoughts

All told, effective and enduring fiscal consolidation through rationalising subsidies and improving tax collections, while simultaneously investing in sustainable public infrastructure for job creation and crowding in private investment are the focus areas of this year’s budget. Fiscal consolidation will allow India the flexibility to run a sustainable current account deficit – which is needed at this stage – without fear of a balance of payments crisis.

For a pre-election budget, the expectation was of a lazy budget, excessive in rhetoric and short on substance. It has however been the opposite – thrifty in rhetoric and plentiful on substance. But the government cannot afford to take its foot off the reform pedal. One success indicator for that will be an improved tax-to-GDP ratio, that for the central government currently hovers around 11%. To get it in the teens will mean reducing the compliance cost of paying taxes. A good start would be to seriously estimate what it costs to pay taxes – in other words, estimate the compliance costs, and then begin to target its reduction. A broader tax net will be the inevitable outcome; and the more fiscal room, the happier the result for the government. After all, that’s what the role of the government should be – to use the available fiscal room to go where private sector will not.

Further Reading

- Forbes, N (2022), The Struggle and the Promise, Harper Collins.

- Government of India (2015), 'Economic Survey 2014-15', Ministry of Finance.

22 February, 2023

22 February, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.