While girls are now at par with boys in school enrolment, they continue to lag behind in terms of the number of years spent in formal education. In this context, this article assesses how girls' educational outcomes have been impacted by Mahila Samakhya - a programme that sought to empower women within local communities in rural India, to challenge traditional gender roles that may be restricting girls' education.

Girls’ education is a development priority across low- and middle-income countries. While a UNESCO report (2020) notes that gender parity in primary enrolment has undeniably reduced in many low-income-countries, obstacles to girls’ continuing education persist, partially driven by complex social and cultural norms.

A typical education intervention mainly targets material resources or infrastructure, with little attention to gender norms in the community (for example consider the case of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, an input focused initiative of the Government of India to achieve universal elementary education (Nandi et al. 2023)). In this context, we shine the spotlight on a unique programme in India, called Mahila Samkhya (MS), which was initiated by the Government of India in 1989. Attributing the gender disparity in education to traditional gender roles, MS aimed to empower women in local communities to address the underlying issues.

In new research (Bhuwania, Mukherji and Swaminathan 2024), we investigate the impact of MS on girls’ formal educational attainment, the probability of completion of primary and secondary levels of education, and child marriage.

The history of Mahila Samakhya

The programme was launched as part of the National Policy on Education (NPE) 1986, representing a pioneering effort to address gender disparity in education in rural areas. Influenced by the women’s movements of the 1970s and 1980s in India, the NPE recognised the symbiotic relationship between education and empowerment. The MS programme departed from conventional government approaches at the time, rejecting target-oriented and paternalistic strategies in favour of empowering marginalised women in rural communities.

The programme's transformative approach involved forming sanghas (groups) to collectivise marginalised women, providing a platform to address their needs and aspirations. MS sought to empower women by giving them skills to challenge established gender norms, particularly those hindering girls' education. By focusing on critical thinking and awareness, MS aimed to break the cycle of gender discrimination and encourage mothers to invest in their daughters' education. Sanghas facilitated community participation, raised issues in village councils, and engaged with government functionaries, creating an intermediate non-government structure. This decentralised approach allowed women to negotiate and voice their concerns, changing the traditional State-led conversation on governance to a community-driven initiative.

Operating in backward districts with historically vulnerable groups and poor educational outcomes, MS covered 55,402 active sanghas with over 1.4 million registered women in 2014. In 2015, the central government merged MS with the National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM), resulting in a loss of budgetary support for the programme. Currently, the programme operates in states like Kerala and Karnataka, where state budgets fund its continuation.

Data and methodology

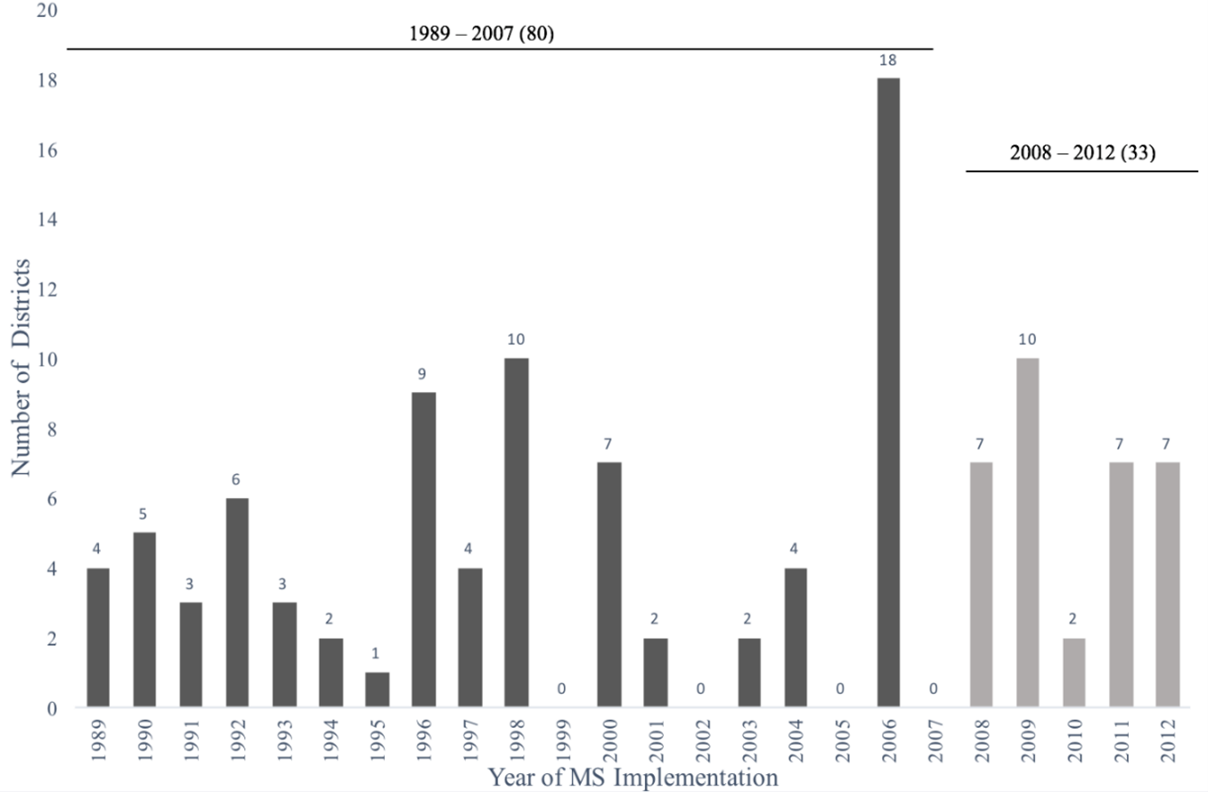

We use the nationally representative District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3), 2007-2008, that presents data on health, education, and other socioeconomic characteristics of individuals aged 15-49 years. We restrict the sample to include only rural areas because MS was a rural programme. Further, we gathered data on the implementation of MS until 2012 from MS state headquarters through their annual reports and merged it with DLHS data. Figure 1 shows the phased rollout of MS during the study period 1989-2012.

Figure 1. Phased rollout of Mahila Samakhya, 1989-2012

Exploiting the phased rollout of MS across districts over time, our difference-in-differences (DiD)1 empirical strategy hinges upon the identification of girls exposed to MS according to their district of residence and age at the time of MS rollout. Districts that introduced MS by 2007 are considered ‘treatment’ districts (80 in number), and all districts that adopted MS after DLHS-3 was conducted are considered ‘comparison’ districts (33 in number). We hypothesise that MS is more likely to impact the education of girls who are younger at the time of MS rollout. Therefore, we capture varying levels of exposure to MS by dividing girls into four categories, indicating their age at the time of MS initiation in their district of residence: (i) 0-6 years old, (ii) 6-12 years old, (iii) 12-18 years old, and (iv) >18 years old. The age group over 18 is the unexposed reference group since their education is least likely to be affected by MS.

We compare completed years of education across these groups in the treatment districts to the education levels among women belonging to the same age groups in the comparison districts. We control for possible confounding factors such as caste, religion, wealth, and land ownership, in order to isolate the impact of the programme on this educational outcome among women. Yet, an important concern could arise due to the potential impact of other programmes, national- or state-level, that might contaminate our comparison of women in MS and non-MS districts across different age groups. We account for such supply-side concerns by comparing the education trajectories of girls and co-located boys. Routine education programmes (such as Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Operation Blackboard, etc.) will affect both genders, while MS engaged only with women and girls. Contrasting girls' trajectory with that of boys will allow us to capture the incremental effects attributable to MS alone.

Findings

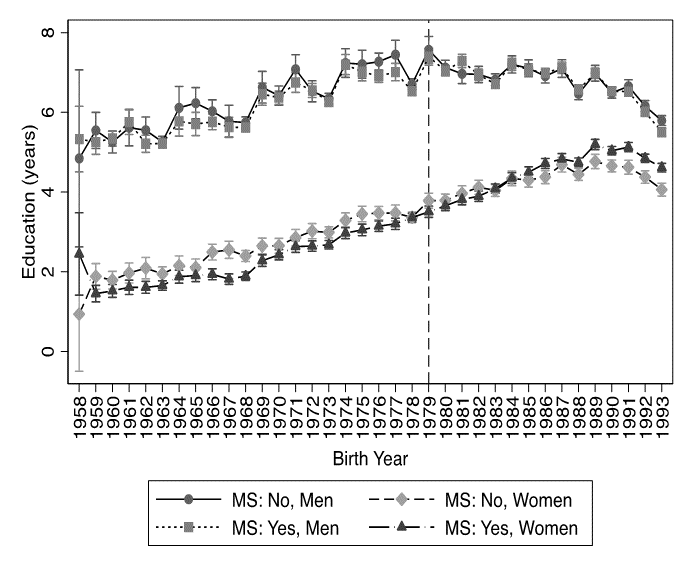

We chart the education trajectories of women and men born during 1958-1993 across MS and non-MS districts in Figure 2. We expect no impact of MS until 1978, as the median age of these individuals was over 20 years when MS was rolled out. Starting in 1979, as the presence of and exposure to MS increased, women’s education in MS districts surpassed that of women in non-MS districts. However, there was no discernible difference in men’s education on account of MS.

Figure 2. Years of education for women and men in MS and non-MS districts

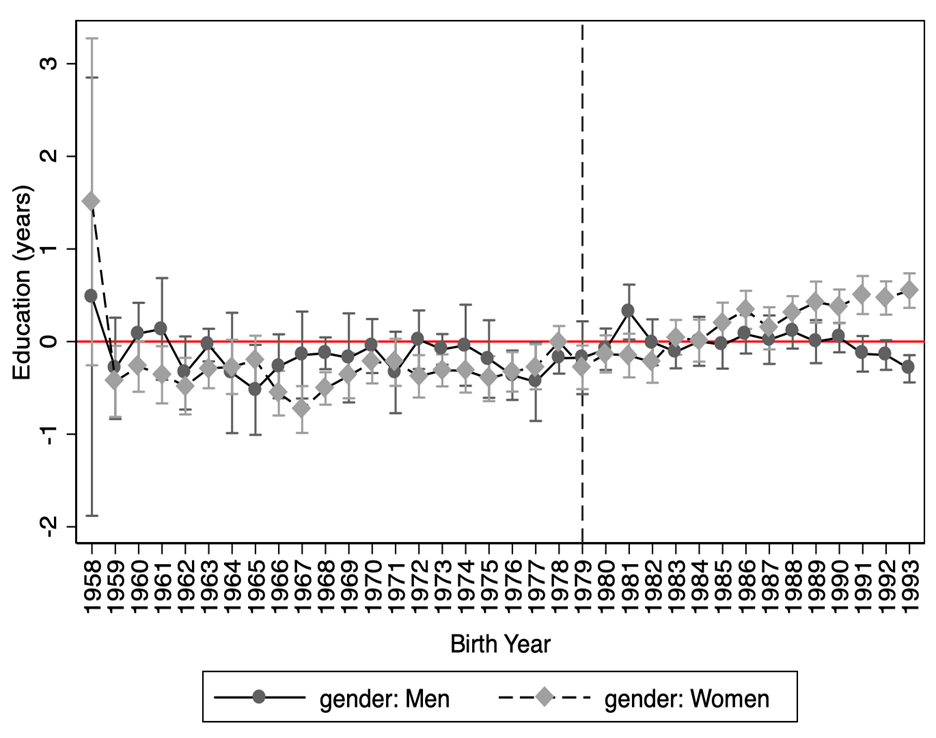

Figure 3. Difference in education levels between MS and non-MS districts for women and men

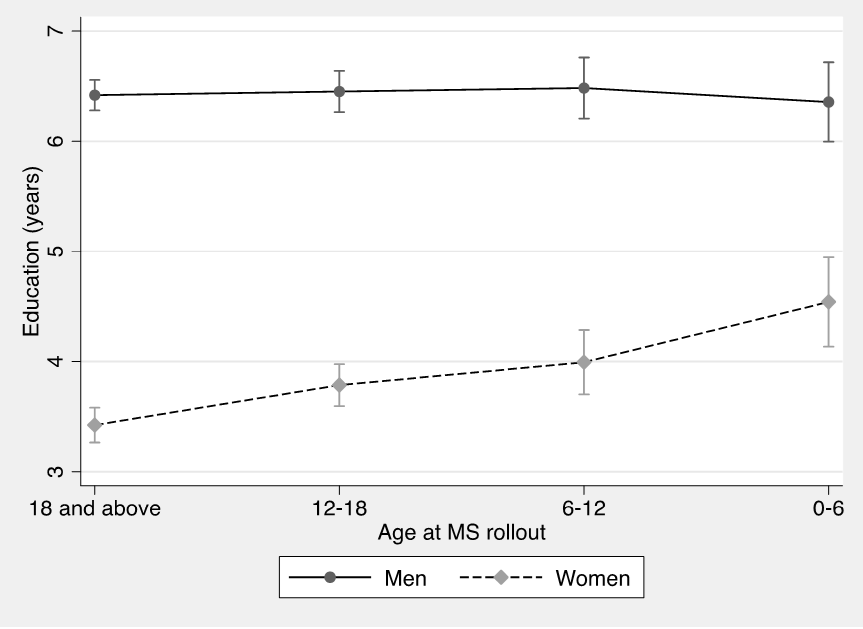

Figures 2 and 3 show that women in MS districts tended to have lower years of completed education in the older cohorts, prior to the roll-out of MS – indicating purposive programme placement. We control for such baseline differences using our DiD estimates which indicate that women in MS districts received additional years of education compared to those in non-MS districts. The effects are most significant for the youngest women, aged 0-6 years at the time of MS rollout, who gained an average of 0.89 years in education on MS exposure. For successively older age groups, we find smaller but significant gains in education. We find no such impact for men. We formally model this using a ‘triple-difference’ estimator2; our estimates suggest that women who were 0-6 years of age at the time MS was rolled out experienced 1.18 additional completed years of education over men who resided in the same primary sampling unit, and sometimes even in the same household. Figure 4 clearly illustrates that, while MS had no impact on men, its impact consistently increased among women as we moved from older to younger age groups at the time of MS rollout.

Figure 4. Impact of MS on women and men

Our findings have implications for gender equity. We observe that MS had a stronger impact in states that fared poorly on pre-existing levels of gender norms and attitudes towards women’s rights, as reflected by the Gender Equality Index (GEI). We also find that the length of exposure to MS matters. Even among the same age groups, MS had a larger impact in districts where it was operational for a longer time.

We examine a series of additional outcomes using the same strategy. Among the youngest women, MS increased the probability of completing lower primary, upper primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary levels by 8.15 percentage points, 7.62 percentage points, 4.38 percentage points, and 2.10 percentage points, respectively. Older age groups showed improvement, but the magnitude reduced with age and level of schooling. MS also reduced the probability of marriage before age 15 by 4.53 percentage points and that of marriage before 18 by 5.31 percentage points.

We speculate on two mechanisms of change. First, MS could have enhanced women’s negotiating powers within the household, which positively impacted girls’ education. Second, by encouraging women to speak up in public spaces and challenge governance institutions, MS could have increased women’s voice in the community to enable their needs to be expressed in public forums like the panchayat, or with government officers to identify gendered public needs.

Conclusion

Our findings emphasise the importance of interventions challenging gender norms and providing a broader perspective on reducing educational disparities. What we learn is that broad-based empowerment programmes can catalyse demand for education but require consistent and sustained effort to generate impacts. These findings have policy implications for gender equality advocates and policymakers. Challenging gender norms requires more than legislation and material resources; it also takes community mobilisation and a long-term commitment.

Notes:

- A difference-in-differences strategy is used to compare the evolution of outcomes over time in similar groups, where one was impacted by an event or policy – in this case, the introduction of MS in their district in 2007– while the other was not.

- A 'triple difference' (DDD) estimate compares the DiD (as computed above) for women (who were impacted by MS) with the same DiD for men (who were not impacted by the programme).

Further Reading

-

Bhuwania, Pragya, Arnab Mukherji and Hema Swaminathan (2024), “Women’s education through empowerment: Evidence from a community-based program”, World Development Perspectives, 33: 100568.

- Nandi, Arindam, Nicole Haberland and Thoai D Ngo (2023), “The impact of primary schooling expansion on adult educational attainment, literacy, and health: Evidence from India’s Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan”, International Journal of Educational Development, 102: 102871.

-

UNESCO (2020), ‘A new generation: 25 years of efforts for gender equality in education’, Global Education Monitoring Report – Gender Report, UNESCO.

11 March, 2024

11 March, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.