Intergenerational mobility contributes to social stability and cohesion, and is associated with higher, more inclusive economic growth in the long-term. This article presents global trends in absolute intergenerational mobility, captured by the share of a generation that surpassed their parents in education. It shows that the global picture on absolute mobility is sobering, particularly for the developing world, as it has stopped rising at a much lower level of overall education attainment than in high-income economies.

In September this year we published a blog post that examined global trends in relative intergenerational mobility, based on our new global study, 'Fair Progress? Economic Mobility across Generations around the World’. Relative mobility is the extent to which an individual’s position on the socioeconomic ladder in a generation is independent of their family background. We reported that for large parts of the world’s population, an individual’s chances of success in life are far too closely tied to the socioeconomic status of their parents. This is even more the case in the developing world (including India); and the average developing country has seen almost no improvement in this measure of social mobility since the generation born in the 1960s. This post, based on the same global study, will be about global trends in absolute intergenerational mobility, which is about the extent of progress a generation has made compared to the previous generation, whereas relative mobility reflects the extent to which progress has been fair. We argue, backed by economic theory and evidence, in our report that higher mobility, both absolute and relative, are likely to contribute to social stability and cohesion and are associated with higher and more inclusive economic growth in the long-term.

In most societies, parents would like to see their children have a higher standard of living, and with it a better life than they had themselves. When individuals are asked, they too tend to consider their parents as a natural benchmark for their own economic progress (Goldthorpe 1987, Hoschschild 2016, Chetty et al. 2017). A simple measure of absolute mobility that captures this notion of progress is the share of a generation who surpassed their parents in income or education. Chetty et al. (2017) find that the US did exceptionally well by this measure for the generations born in the 1940s and 1950s, 90% of who had higher incomes than their parents. Absolute mobility in the US has since faded to around 50% for those born in the 1980s. How has absolute mobility fared elsewhere in the world? In which economies do children have the best chances to improve upon their parents? Are the highest rates of absolute mobility observed in economies that are starting from a low base?

Our global study addresses these questions, and some more, using the newly developed Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility (GDIM), which provides estimates of intergenerational mobility – absolute and relative – for 148 economies representing 96% of the world’s population born in the 1980s, who are the youngest generation of adults to have completed their education. For 111 economies, or 87% of the world’s population, estimates of mobility span five decades: from those born in the 1940s to those born in the 1980s. We focus primarily on mobility in education, since human capital is a key aspect of economic well-being and educational mobility has a strong association with income mobility. And crucially, intergenerational data on education is much more widely available than that on income. For absolute mobility, our primary measure is the share of individuals in a generation who have higher educational attainment than their most educated parent.1 This is a measure of mobility in educational qualifications rather than skills, since it does not consider the quality of education received by individuals.

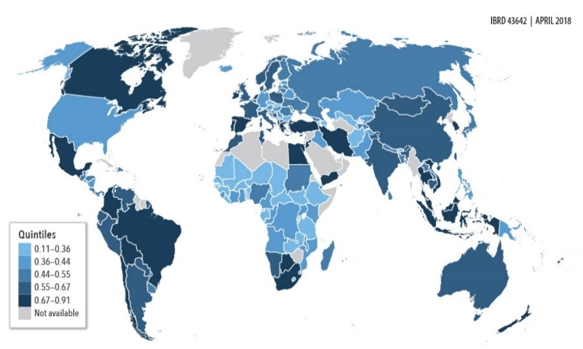

Figure 1. Absolute mobility in education around the world

The study finds that absolute mobility varies considerably across the 148 economies (for those born in the 1980s), with a clear geographic pattern (Figure 1; darker colors indicate higher levels of mobility). Sub-Saharan Africa stands out as the region with some of the lowest rates of absolute mobility, which is as low as 12% in some of the poorest or most fragile economies of the region, compared to over 80% in parts of East Asia. Absolute mobility for the ‘80s generation is also relatively high in Europe, Canada, Latin America, parts of the Middle East, and South Africa. On average, absolute mobility is significantly lower in developing (low- and middle-income) economies than in high-income economies (based on the latest World Bank classification).

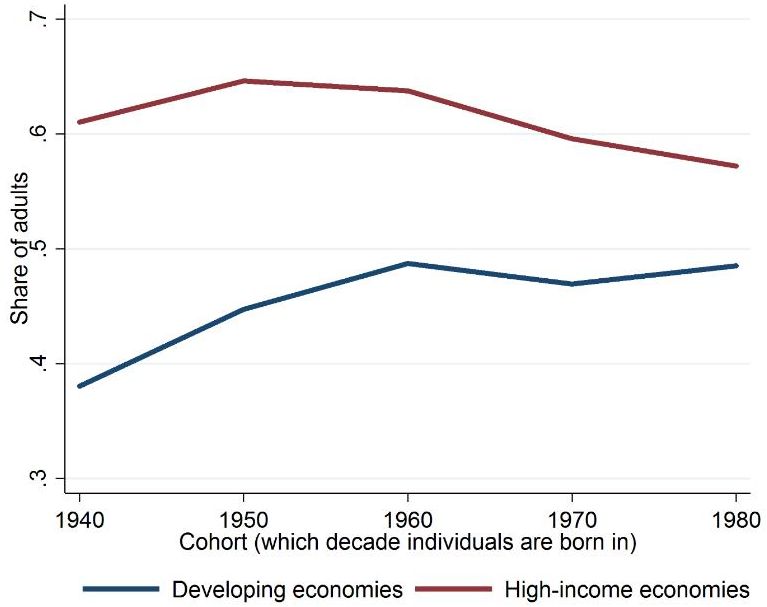

Figure 2. Absolute mobility from the 1940s to the 1980s cohort

To see whether the gap between high-income and developing economies extends to older generations, average absolute mobility for each group is tracked over time. The averages are unweighted by population, which means that they represent the average mobility of economies and not of the average individual in each group. Figure 2 shows that average absolute mobility is lower in developing economies throughout the 50-year period. The gap is larger for those born in the 1940s and 1950s, and has narrowed over time, largely because of a decline in average absolute mobility in high-income economies since the ‘60s generation, even as it stopped rising in the developing economies.

That average absolute mobility has been falling in high-income economies is not surprising – it becomes increasingly difficult to surpass one’s parents in education as tertiary attainment rates increase from one generation to the next. What is more surprising is that absolute mobility continues to be much lower in the developing world and has stagnated for the last 30 years, given that the scope for surpassing the education level of one’s parents is higher in these economies. For example, the tertiary attainment rate among the parents of the ‘80s generation in developing economies is comparable to that of the parents of the ‘50s generation in high-income economies.

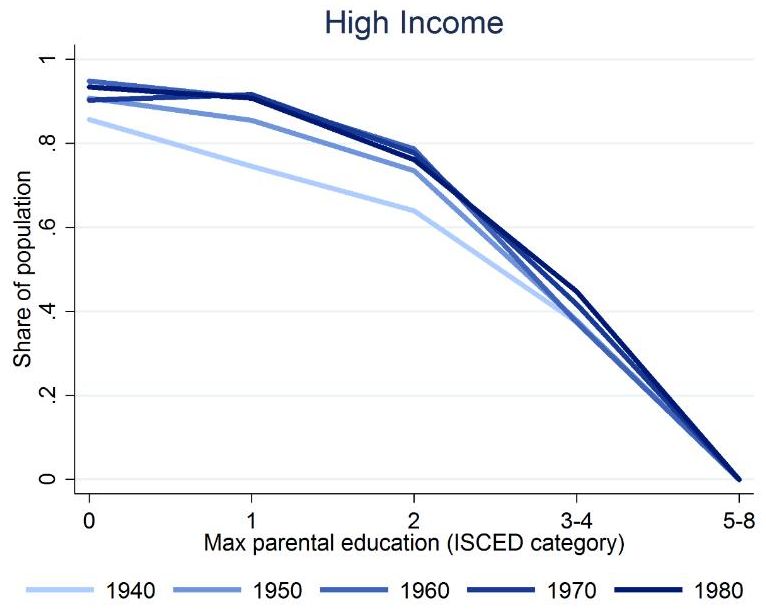

In Figure 3, we plot the percentage of children who have more education than their parents against the education of their parents for the average high-income economy. As one would expect, absolute mobility (conditional on parental education) declines with parental education. If the same pattern were also to apply to the average developing economy, absolute mobility would be higher in the developing world (where parents have lower levels of education), which is the opposite of what we observe empirically. A likely explanation for this apparent paradox is the lower availability of resources, parental and public, to invest in children in developing economies. And if that is the case, individual born in poorer (and less educated) households are more likely to be constrained in their mobility, which could lead to a different relationship between absolute mobility and parental education in the developing world.

Figure 3. Absolute mobility versus parental education (high-income)

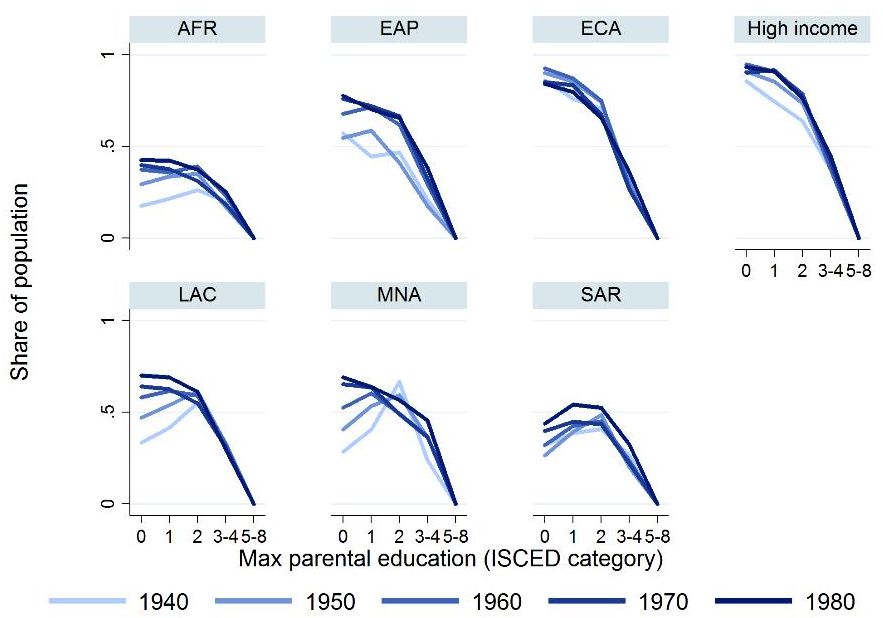

It turns out that the relationship between absolute mobility and parental education is indeed different in developing economies, more like an inverted-U than the declining function seen in high-income economies (Figure 4). The different panels of Figure 4 correspond to the average economy in each of the six different developing regions, as classified by the World Bank. The different shades of blue refer to different cohorts, with darker shades denoting younger cohorts. The inverted-U suggests that individuals with less-educated parents, who are likely to be poorer, are also less likely to be upwardly mobile in developing economies. That the inverted-U is most pronounced in the two poorest regions, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, is particularly suggestive: poorer the region, more likely it is that individuals born to parents who do not have an education lack the means to get an education, which creates something akin to a poverty trap. Fortunately, this poverty trap appears to be weakening with each new generation, as the inverted-U gradually morphs into the pattern observed for the average high-income economy as regions become richer.

Figure 4. Absolute mobility versus parental education (by region)

The global picture on absolute mobility in education is thus sobering, particularly for the developing world, as it has stopped rising at a much lower level of overall education attainment than in high-income economies. Behind the story of the averages are however causes for optimism. Rapid improvements from the ‘50s to the ‘80s generations occurred in the developing regions that are primarily middle-income – East Asia and Pacific, Latin America and Caribbean, and the Middle East and North Africa – to the extent that they match or surpass high-income economies in absolute mobility among the ‘80s generation. And even in Sub-Saharan Africa, rapidly rising enrolments for children born after the 1980s suggest that absolute mobility may be on the rise. These findings, along with other highlights from our global study – on topics such as relative mobility in education and income, multi-generational mobility, and the drivers of mobility – will be featured in future blog posts.

This is a revised version of a post that was first published on the World Bank’s Let’s Talk Development blog: http://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/which-countries-do-children-have-best-chances-surpass-their-parent-s-education?CID=POV_TT_Poverty_EN_EXT

Notes:

- Those with parents who have attained the highest (tertiary) level of education are excluded – when either parent has completed a tertiary degree, it is no longer possible for the offspring to have more education. An alternative way of dealing with this so-called “ceiling effect” yields comparable results (see the report).

Further Reading

- Chetty, Raj, David Grusky, Maximilian Hell, Nathaniel Hendren, Robert Manduca and Jimmy Narang (2017), “The fading American dream: Trends in absolute income mobility since 1940”, Science, 356(6336): 398-406.

- Goldthorpe, JH (1987), Social mobility and class structure in modern Britain, Oxford University Press.

- Hoschschild, AR (2016), Strangers in their own land: Anger and mourning on the American right, New Press.

- Narayan, A, R Van der Weide, A Cojocaru, C Lakner, S Redaelli, D Mahler, R Ramasubbaiah and S Thewissen (2018), Fair Progress?: Economic Mobility Across Generations Around the World, Equity and Development series, World Bank, Washington DC.

28 November, 2018

28 November, 2018

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.