In the fourth article in the Ideas@IPF2023 series, Ruchir Agarwal describes the impact of two economic shocks – the financial crisis of 2018-20 and the Covid-19 pandemic – on the Indian financial system. He attributes the economic slowdown during this period to a ‘macro-financial spiral’, and highlights the efforts being taken to restore India’s financial health after these shocks. He concludes with the challenges and opportunities that need to be taken into account when framing financial reforms.

India's growth story depends on the vitality of its financial system. Within the span of five years, the Indian economy has endured two unprecedented shocks: the 2019 economic slowdown triggered by a financial crisis, and the Covid-19 pandemic. As we navigate the aftermath of these shocks, one vital question emerges: how resilient will India's financial system be in the face of future challenges?

In this context, this article embarks on three missions. First, it examines the origins and aftermath of the 2018-20 Indian Financial Crisis, sparked by a run on shadow banks. Second, it examines how India fortified its financial system in the wake of the financial crisis and the pandemic, and consequently shielding itself from the global banking disruptions of 2023. Finally, it gazes ahead at potential challenges and opportunities, sketching a blueprint for key reforms.

Recent history: A financial snapshot

Historically, development banks or All-India Financial Institutions have been pivotal in provision of long-term infrastructure lending. However, in the 1990s, several significant development banks faltered. This led to public sector banks (PSBs) assuming a more dominant role in infrastructure lending.

Throughout the 2000s, there was a surge in infrastructure lending in India due to the country’s escalating infrastructure requirements. Public-private partnerships thrived during this period, and Indian banks, especially PSBs, ramped up their project finance involvement. By 2014, due to their widespread presence nationwide and their significant role in infrastructure lending, PSBs provided about 70% of total bank credit to the real economy.

This period also marked significant growth in total bank lending from both private and public banks. From 2005 to 2013, the total bank lending expanded by over 15% annually in real terms. Notably, banks’ engagement in major infrastructure projects continued to rise, even against the backdrop of the global financial crisis of 2007-09.

However, by the early 2010s, the banking system faced challenges. Governance lapses in infrastructure projects significantly increased the risk of stressed assets in PSBs, and the system experienced a credit misallocation problem known as loan evergreening or ‘zombie lending’. Under-capitalised banks rolled over loans to large, struggling borrowers to avoid declaring them as non-performing assets (NPAs). By FY2016-17, these large borrowers constituted over half of all bank loan portfolios and almost 90% of NPAs in the banking system.

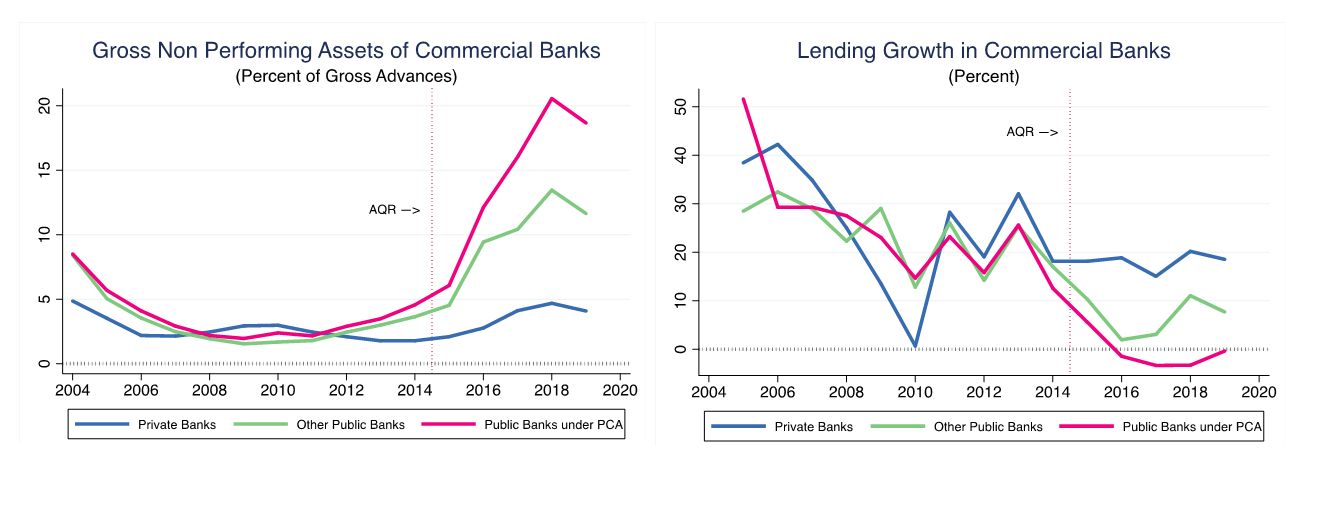

Recognising the severity of this challenge, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) prioritised addressing the NPA problem in the mid-2010s. A pivotal development was the asset quality review (AQR), a regulatory exercise aimed at identifying and rectifying discrepancies in loan classification by banks. This process revealed substantial underreporting of NPAs, leading to a collapse in public bank lending (see Figure 1). The sudden decline in credit availability created a vacuum that spurred the growth of shadow banks, or non-bank financial companies (NBFCs), which witnessed a surge in lending activity.

Figure 1. Growth of NPAs and decline in PSB lending

Source: Author’s calculations using RBI data

Note: The AQR led to 12 banks (of which 11 were PSBs) being put under ‘Prompt Corrective Action’, leading to a sharp decrease in public bank lending. These banks are depicted by the pink line.

The subsequent demonetisation on 6 November, 2016 impacted the financial system by inducing an abrupt and substantial reduction in cash circulation. This move generated both short-term and long-term effects on various sectors, including shadow banking and real estate. Despite the initial liquidity crisis, demonetisation indirectly benefited shadow banks by increasing deposits in the formal banking system and lowering interest rates, thereby boosting demand for credit from NBFCs.

The Indian financial system faced additional challenges with the high-profile defaults of Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services (IL&FS) and Dewan Housing Finance Limited (DHFL) in 2018 and 2019, exposing the vulnerabilities within the shadow banking sector. These defaults set off a contagion effect, culminating in a liquidity crisis and loss of confidence in NBFCs.

On the eve of the pandemic, India was already grappling with a major economic slowdown. By March 2020, marking the end of the last quarter of FY2019-20, GDP growth had steeply fallen to just 2.9%, a stark contrast from the 7% decadal average. For the first time in over a decade, aggregate investment – which accounted for a quarter of GDP – experienced continuous contraction, declining by more than 4% over three successive quarters.

Thus, the Covid-19 pandemic struck at a time when the Indian financial system was already grappling with these vulnerabilities. The pandemic’s unprecedented disruption to economic activity and trade led to widespread job losses, business closures, and further strain on an already fragile financial sector. The government and the RBI implemented several unprecedented measures to cushion the economy, including fiscal stimulus packages, moratoriums on loan repayments, and liquidity injections. However, the pandemic also introduced new challenges, including a delay in the repair of the financial system that was needed after the shadow banking crisis.

The Indian Financial Crisis of 2018-20

The events that unfolded in India between September 2018 and March 2020, although not widely recognised as such at the time, bear the hallmarks of a financial crisis. This notion may court controversy, but let’s examine why it holds true.

A financial crisis is often characterised by severe disruptions in financial intermediation, widespread defaults, and panic-driven runs on banks. During this period in India, an unusual run on shadow banks occurred. Large institutional depositors (for example, corporates) withdrew from mutual funds, leading to a startling contraction in funding for commercial paper and debt markets, thereby disrupting financial intermediation. The subsequent defaults by IL&FS in September 2018 and DHFL in June 2019 caused a palpable sense of panic in the market, akin to a traditional bank run leading to severe economy-wide damages.

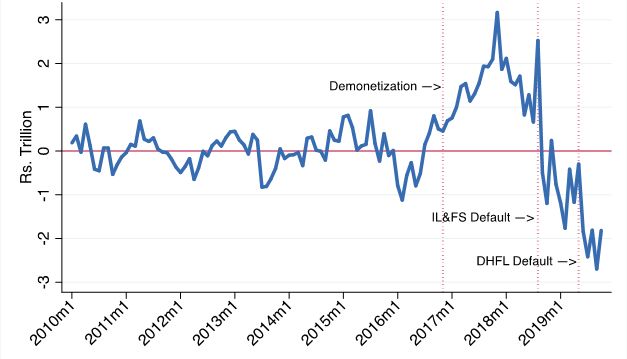

The total loss mutual funds incurred because of their exposure to IL&FS and DHFL was around Rs 25 billion for each, adding up to roughly 0.2% of mutual fund assets or 0.01% of GDP (see Figure 2). However, these minor exposures caused major stress, with similar dynamics as traditional bank runs. This led to massive system-wide outflows from the mutual fund industry. In response, mutual funds drastically cut funding to shadow banks, which subsequently reduced credit flows to the real economy. Due to inter-linkages between traditional and shadow banking systems, problems spread to traditional banks after DHFL’s default, causing a steep decline in lending.

Figure 2. Gap in mutual fund assets under management

Note: U5MR stands for under-five mortality, IMR stands for infant mortality, and NMR stands for neonatal mortality.

Source: Author’s calculations using data from the Association of Mutual Funds in India (AMFI)

Note: Gap in assets under management (AUM) is defined as the difference between actual AUM and 2010-16 trend AUM

This raises two central questions regarding India’s economic slowdown. First, why did the defaults lead to system-wide stress and such large outflows from mutual funds? Second, why did a relatively small shock have such a large, negative, economy-wide impact?

India’s macro-financial spiral

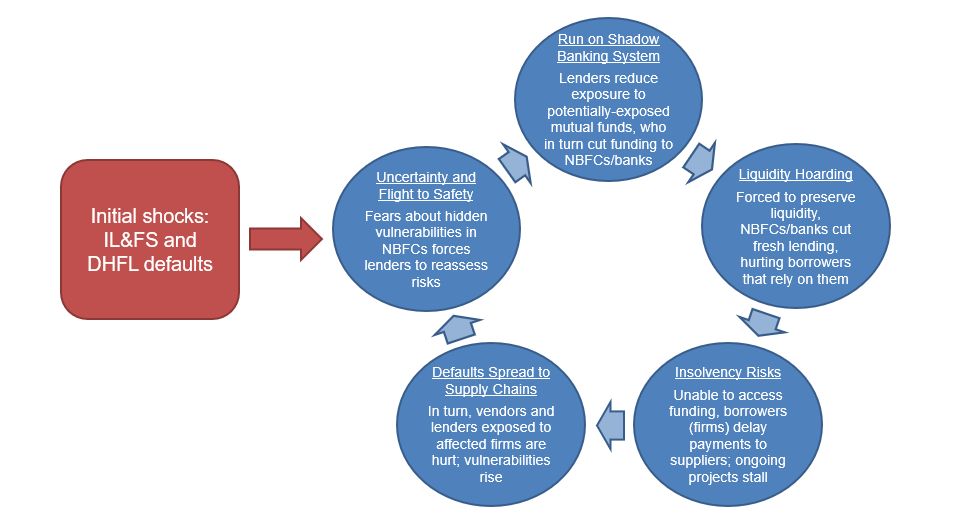

The explanation revolves around a series of mechanisms that the author refers to as “India’s macro-financial spiral”, that (i) led to the two system-wide runs on the shadow banking system, and (ii) amplified these runs economy-wide.

In brief, the IL&FS group defaulted on its debt obligations in September 2018. Rated AAA1 until its default by some credit rating agencies, the default shocked the financial system. Fears and uncertainties about hidden vulnerabilities in NBFCs and infrastructure/real estate sectors led lenders to reassess risks. This initiated a flight to safety, starting with a system-wide run on the shadow banking system. The reasons include varying practices across mutual funds in valuing IL&FS debt and inconsistent timing of haircuts on such securities. This created a first-mover advantage, similar to a classic bank run, prompting investors to withdraw from mutual funds.

Limited funding access forced NBFCs to hoard liquidity and reduce new lending, impacting borrowers and real estate developers. As a result, credit growth slowed down, affecting the real economy, especially those sectors that relied heavily on shadow banking for credit. The real estate and construction sectors were hit particularly hard, given their dependence on NBFCs and Housing Financial Companies for financing.

The slowdown in the real estate and construction sectors led to a decrease in aggregate demand, putting stress on the economy. This economic stress, in turn, led to lower corporate revenues and reduced repayment capacity, increasing the risk of further defaults in the shadow banking system.

The increased risk of default fueled the flight to safety, reinforcing the cycle of stress in the financial system. This feedback loop between the financial system and the real economy created a macro-financial spiral, amplifying the impact of the initial shock from the defaults of IL&FS and DHFL. These mechanisms are conveyed in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Description of the macro-financial spiral ensuing post-IL&FS and DHFL default

A few months later, the default of DHFL restarted this spiral, with the impact this time also spreading to banks, as the default of DHFL deepened worries about the entire financial system’s cross-exposures to the troubled NBFC and the real estate sectors.

During this period, there was a significant contraction in domestic lending to the private sector, which fell from nearly 10% of GDP in FY2018-19, to roughly 3% in FY2019-20 (excluding funds from the capital markets).

Restoring financial health after the crisis and the pandemic

From implementing accommodative monetary policies and emergency liquidity provisions to introducing loan repayment moratoria and credit guarantee schemes for MSMEs, the authorities implemented a wide range of measures to fortify the economy in 2018 and 2019, and as a Covid-19 emergency response.

For instance, the RBI’s liquidity policy followed a conventional lender-of-last-resort approach, without expanding the scope of lender-of-last-resort operations. It focussed on injecting aggregate liquidity into the system, and encouraging banks to channel excess liquidity to the NBFC sector. Measures taken included significant open market purchases, sizable net purchases of foreign currency, and various initiatives to encourage banks to channel excess liquidity to the NBFC sector

The RBI also implemented broad monetary policy actions in response to the slowdown including interest rate cuts and measures to improve policy rate transmission. The RBI began cutting rates in February 2019, reducing the policy repo rate by 135 basis points. However, in December 2019, they paused the cuts due to rising food price inflation and reduced policy rate transmission, keeping the repo rate at 5.15% while maintaining an accommodative stance.

Several macro-financial support and supervisory actions were implements, including cleaning up the NBFC sector by withdrawing the license of nearly 2,000 small NBFCs between 2018-19; providing relief to Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSME) through a one-time restructuring of existing loans to MSMEs; strengthening regulation and supervision by the RBI; mergers that would consolidate ten public banks into four entities to create larger, more efficient banks that could better serve the credit needs of the Indian economy; and expanded support from All-India Financial Institutions.

An even broader set of measures were implemented during Covid-19 – this included the loan repayment moratorium from March to August 2020, the introduction of the Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme in May 2020, a series of interest rate reductions to stimulate economic growth and encourage banks to lend more, and enhanced liquidity support to banks and non-banks, among others.

These measures were instrumental in strengthening the financial system and ensuring its continued functioning even in the face of unprecedented challenges. Moreover, these concerted efforts did more than just strengthen the financial system domestically. They also acted as a protective shield, insulating the Indian financial system from the adverse circumstances that led to the collapse of several Western banks in 2023.

While the global banking sector was grappling with a series of bank failures after the default of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023, the Indian financial system, fortified by proactive repair and restructuring initiatives, demonstrated resilience. The focus on addressing asset-liability mismatches after the IL&FS default, along with different business models, and the recent restructuring of potentially weak links (such as YES Bank), ensured that Indian banks were well-prepared to weather the global banking storm.

Reform priorities

The key takeaway from this research is that the future trajectory of Indian growth, whether a modest 5.5% or a bold 7.5%, rests significantly on the progress of ongoing financial sector reforms. There are currently three central challenges facing India going forward.

The first is addressing the funding imbalance between traditional and shadow banks (the ‘Great Funding Imbalance’). This imbalance stems from public sector banks and a few large private banks enjoying access to affordable depositor funding, while the rest of the system faces funding scarcity despite vast lending opportunities in the Indian economy. The imbalance was muted during the Covid-19 crisis, mainly due to the RBI’s massive injections of aggregate liquidity. However, persistently high inflation may put greater pressure on the RBI to withdraw liquidity, and funding imbalance will become prominent again. Any privatisation efforts or reorganisation of the Indian financial system is an opportunity to address the Great Funding Imbalance.

The second is expanding credit accessibility across the country (the ‘Financial Deepening Hurdle’). Bank credit-to-GDP ratios remain very low in poorer states (for instance, the bank credit-to-GDP ratio in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, two of the country’s most populous states, is much lower than the national average). When some regions have limited access to credit, it can lead to a less efficient allocation of resources, hampering economic growth and exacerbating regional disparities. Therefore, India’s financial sector reform must be a part of a comprehensive strategy to overcome India’s Financial Deepening Hurdle

Finally, striking the right balance between economic growth, financial stability, and nurturing national champions (‘The Growth Strategy Trilemma’) poses a complex challenge for government, since pursuing any two of these objectives necessarily comes at the cost of partially sacrificing the third. Potential opportunities can also arise from India’s digital payments revolution and leveraging reforms like the 2016 Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code.

To tackle these challenges, a reform agenda would need to be centered on ten policy areas: i) strengthening regulation and supervision, ii) managing systemic risk, iii) improving asset quality, iv) enhancing the framework for bad loans and bankruptcy, v) reforming public sector banks, vi) restructuring the financial sector, vii) deepening the financial sector, viii) improving monetary policy transmission, ix) improving the emergency liquidity framework, and x) supporting real estate transactions. Through these reforms, India can lay the groundwork for a more resilient and stable financial system that bolsters long-term growth and development.

This is a summary of a preliminary paper draft prepared for the NCAER India Policy Forum 2023.

Note:

- Investment grade is a credit rating that signifies that a bond presents a relatively low risk of default. Rating firms use different designations to identify a bond's default probability - "AAA" and "AA" (high credit quality or low default probability) and "A" and "BBB" (medium credit quality) are considered investment grade, while credit ratings below these are considered low credit quality (or high default probability).

14 July, 2023

14 July, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.