To protect small, labour-intensive manufacturing enterprises and boost employment, the Indian government reserved certain products for exclusive production by such enterprises. This policy was gradually phased out during 1997-2015. This column finds that dismantling of the reservation, in fact, led to increases in overall employment, driven by entrants into the de-reserved product space and incumbents that were previously constrained by the policy’s size limits.

Governments throughout the world promote small and medium enterprises (SME), often because SMEs are assumed to do a better job of creating jobs than larger enterprises. But do such policies work? We used a natural experiment – the dismantling of a long-standing policy of SME promotion in India – to estimate the causal impact of an SME promotion policy on employment.

Reservation and de-reservation for small-scale industry in India

For the past 60 years, India has attempted to boost employment growth by shielding small manufacturing establishments – known as small-scale industries, or SSI – from competition. Many believed that SSIs, particularly labour-intensive manufacturing enterprises, would be able to absorb surplus labour. Promotion measures have included the types of policies used all over the world: subsidised credit, technical assistance, excise tax exemptions, preference in government procurement, and subsidies for power and capital.

Until 1997, the premier instrument for protecting small establishments in India was the policy of reserving a number of products for exclusive production by small-scale industry. Under this policy, only firms considered to be SSIs – that is, industrial undertakings with up to Rs. 10 million in plant and machinery – were allowed to make reserved products. Firms with plant and machinery values above the SSI threshold were only allowed to make a reserved product if they had been making the product at the time it was de-reserved, or if they began making the product when they were below the threshold. However, these firms were constrained to make no more than they were making at the time the product was reserved (or at the time they surpassed the SSI threshold), unless they committed to exporting most of the excess production.

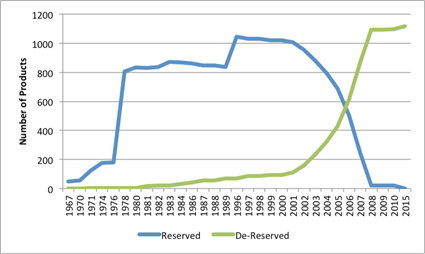

Initially only 47 items were reserved (Figure 1), but by 1996 that number had grown to over 1,000. Proponents of small establishment promotion argued that these policies encouraged labour-intensive growth, mitigated capital market imperfections, and shifted income toward lower wage earners (Hussain 1997). However, critics argued that these policies, in fact, discouraged firm growth, reduced exports, and slowed the overall expansion of the manufacturing sector (Mohan 2002, Panagariya 2008).

Figure 1. Reservation and de-reservation in India

Sources: (i) Data for 1967 through 1989 are from Table 6.3 in Mohan (2002). (ii) Data for 1996 onward are from various publications of the Ministry of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises, Government of India.

Sources: (i) Data for 1967 through 1989 are from Table 6.3 in Mohan (2002). (ii) Data for 1996 onward are from various publications of the Ministry of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises, Government of India. India underwent a major liberalisation of its trade and industrial policies in 1991. Yet, the SSI promotion policy remained intact. However, in 1995, the Advisory Committee on Reservation recognised that SSIs might be shielded from competition to some extent, but still had to compete with a number of large firms that had been ‘grandfathered’ in, as they were making the reserved products prior to the date of reservation. Moreover, following trade liberalisation, SSIs also had to compete with imported goods, which were not subject to the reservation policy. At the same time, growing consumer demand for high-quality goods, and ongoing technological progress, made it more difficult to produce many items in small firms.

In accordance with recommendations of a special committee, the reservation policy was dismantled between 1997 and 2015, with many products removed from the reserved list each year (Figure 1). We used the dismantling of the SSI reservation policy as a natural experiment, to examine its effects on employment (Martin et al. 2017).

Impact of de-reservation

Because different products were de-reserved in different years, we were able to use a difference-in-differences (DID) approach to examine whether de-reservation of a product was associated with a change in employment, relative to products that were not de-reserved. The DID strategy controls for time-invariant, product-specific factors, such as the fact that certain products are more labour-intensive and thus require more employment per unit of output; and for macroeconomic or other shocks, such as recessions, that affect all products in the same way at the same time.

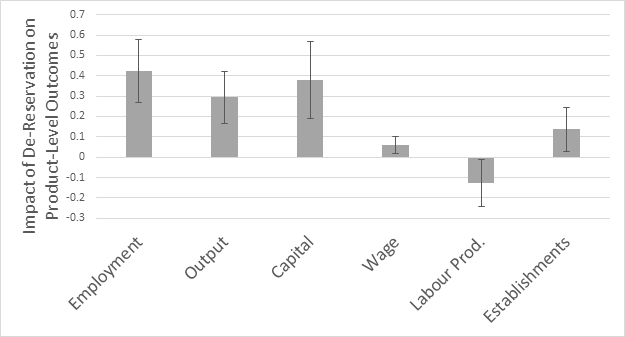

We found that once a product was de-reserved, the number of establishments making that product increased by nearly 15%. In addition, employment increased by 50%, output by nearly 35%, capital by 45%, and wages by 6% (Figure 2 shows the regression coefficients from which these estimates are derived). Note, however, that employment increased by more than output, implying a fall in labour productivity.

Figure 2. Impact of de-reservation on product-level outcomes

Note: Authors’ calculations based on product-level regressions. Bars indicate regression coefficients, where the dependent variable is the log of the outcome; thus coefficients can be (roughly) interpreted as percent changes for products that were de-reserved (relative to those that were not de-reserved). Estimated percent changes in these outcomes, derived from the coefficients, are reported in the text. 95% confidence intervals are shown.

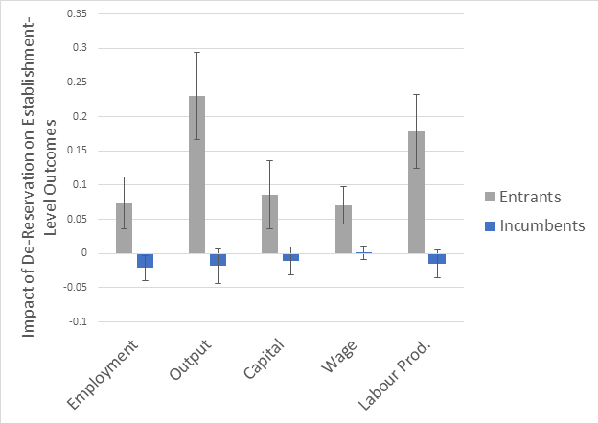

Note: Authors’ calculations based on product-level regressions. Bars indicate regression coefficients, where the dependent variable is the log of the outcome; thus coefficients can be (roughly) interpreted as percent changes for products that were de-reserved (relative to those that were not de-reserved). Estimated percent changes in these outcomes, derived from the coefficients, are reported in the text. 95% confidence intervals are shown. This increase in employment and output was driven by entrants into the product space – that is, establishments that previously did not make the de-reserved product, but which began making the product after it was de-reserved. As Figure 3 shows, entrants into de-reserved product markets increased their employment by 7.7%, their output by 26%, and their capital investment by 9%. Average real wages among entrants increased by 7%. In keeping with the relatively large increase in output relative to employment, labour productivity among entrants increased by nearly 20%.

Figure 3. Impact of de-reservation on establishment-level outcomes

Note: Authors’ calculations based on establishment-level regressions. Bars indicate regression coefficients, where the dependent variable is the log of the outcome; thus coefficients can be (roughly) interpreted as percent changes. Estimated percent changes in these outcomes, derived from the coefficients, are reported in the text. 95% confidence intervals are shown.

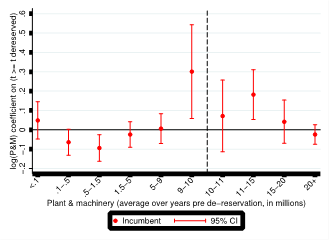

Note: Authors’ calculations based on establishment-level regressions. Bars indicate regression coefficients, where the dependent variable is the log of the outcome; thus coefficients can be (roughly) interpreted as percent changes. Estimated percent changes in these outcomes, derived from the coefficients, are reported in the text. 95% confidence intervals are shown. In contrast, incumbents – establishments that were making the reserved product prior to the de-reservation – decreased their employment by 2.1% following de-reservation, while exhibiting little change in other outcomes. However, this effect was not uniform across incumbents. In fact, we found that incumbents with plant and machinery just below the SSI threshold – with Rs. 9-10 million in historical value of plant and machinery – were constrained by the reservation policy, and unlike the average incumbent, increased their capital investment after the product was de-reserved (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Impact of de-reservation by size of incumbents

If entrants into de-reserved products increased their employment but incumbents decreased employment, what was the overall impact of the de-reservation on employment? To answer this question, we examined how overall formal manufacturing employment in each district in India responded to the district’s exposure to de-reservation. District exposure was calculated based on the pre-existing industrial mix: in other words, districts with more employment in industries that faced de-reservation were considered more exposed to de-reservation. We found that districts more exposed to de-reservation exhibited increases in both employment and output. A district exposed to the average amount of de-reservation between 2000 and 2007 would have experienced a 6% increase in employment.

Implications for SME promotion policy

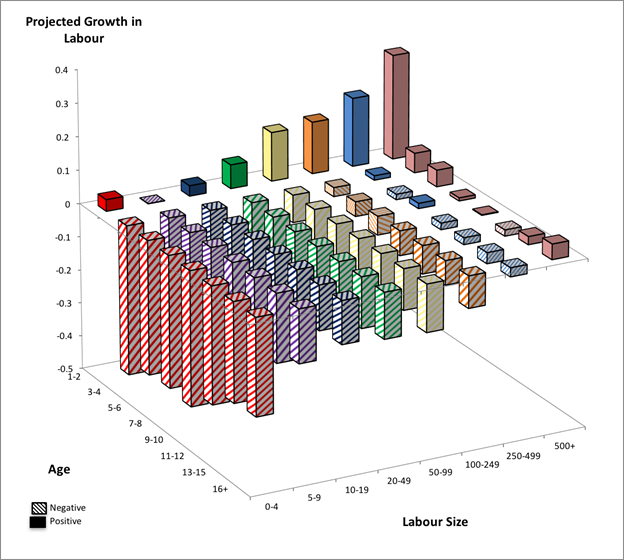

Contrary to the expectations for such policy, we find that eliminating the policy was in fact associated with increases in overall employment, and that these increases were driven by entrants into the de-reserved product space. Our findings are also in keeping with the evidence on the relationship between establishment size and growth in India. We find – as do Haltiwanger et al. (2013) in the United States – that it is young establishments, not small establishments, that exhibit high employment growth (Figure 5). The removal of small-scale reservations increased overall employment by encouraging the growth of younger, larger establishments − those that are most likely to pay higher wages, create more investment, be more productive, and generate growth in employment.

Figure 5. Establishment size, age, and growth in India

Note: Projected establishment employment growth rates for each size and age class. Size is measured as average employment between the previous period observed and the current period. Employment growth is measured as the change in size between one observation and the next, divided by the average size and the number of years between observations. Growth measure accounts for both entry and exit.

Note: Projected establishment employment growth rates for each size and age class. Size is measured as average employment between the previous period observed and the current period. Employment growth is measured as the change in size between one observation and the next, divided by the average size and the number of years between observations. Growth measure accounts for both entry and exit. Further Reading

- Haltiwanger, John, Ron S Jarmin and Javier Miranda (2013), “Who Creates Jobs? Small versus Large versus Young”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2):347-361.

- Hussain, A (1997), ‘Report of the Expert Committee on Small Enterprises’, Department of Small Scale Industries and Business Enterprises, New Delhi.

- Martin, Leslie, Shanthi Nataraj and Ann Harrison (2017), “In with the Big, Out with the Small: Removing Small-Scale Reservations in India”, American Economic Review, 107(2):354-386.

- Mohan, R (2002), ‘Small-Scale Industry Policy in India: A Critical Evaluation’, in AO Krueger (ed.), Economic Policy Reforms and the Indian Economy, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Panagariya, A (2008), India: The Emerging Giant, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

05 December, 2016

05 December, 2016

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.