Keynes propounded that fiscal policy should be countercyclical in nature – expansionary during recession and contractionary during periods of boom. In this post, Aakanksha Shrawan analyses India’s Interim Union Budget for 2024-25, as well as trends in the discretionary spending component of government’s fiscal policy in recent years. She concludes that India seems to be on track towards sound debt management and a higher degree of countercyclicality in fiscal management.

In February, the Interim Budget 2024-25 was approved by the Parliament, with no major announcements regarding changes in the government’s direct and indirect taxation policies. Since the present budget is simply a placeholder ahead of the upcoming general elections (expected to be held across April and May 2024), the people of India are eagerly awaiting the Budget that will be presented post elections.

The government has, however, displayed its intention to rein in deficits and pursue a path of fiscal consolidation, with the Interim Budget pegging the target of fiscal deficit at 5.1% of gross domestic product (GDP) for 2024-25. The 2023-24 revised estimate (RE) of fiscal deficit (5.8% of GDP) was also slightly lower than the budget estimate (BE) of fiscal deficit (5.9% of GDP).1 Further, the government aims to limit the revenue deficit2 to 2% of GDP for the financial year 2024-25 and has almost achieved the 2022-23 target of revenue deficit (3.8% BE versus 3.9% actuals).

Role of the Budget in macroeconomic stabilisation

The new numbers have, once again, brought to the forefront the discussions around the stabilisation features of the Budget. Keynes (1936) propounded that fiscal policy should be countercyclical in nature (that is, expansionary during a recession and contractionary during a boom) since this ensures that by curtailing discretionary expenditures in good times, the government will be able to use this fiscal space to support the economy during downturns and avoid borrowing unless necessary. While the stance of discretionary fiscal policy in advanced economies has been found to be largely countercyclical or acyclical (Gali and Perrotti 2003, Fatas and Mihov 2009, Égert 2010), the fiscal policy in emerging markets is predominantly procyclical or in the initial stages of attaining countercyclicality (Talvi and Végh 2000, Fernández et al. 2021). Huidrom et al. (2016) analysed a sample of more than 100 emerging and frontier markets to show that fiscal policy has transitioned towards procyclicality since the 1980s as a result of a widening fiscal space that is available to accommodate a countercyclical policy.

Changes in fiscal variables such as the fiscal deficit are constituted of changes in two components, namely discretionary spending and non-discretionary or cyclical spending. While the former depicts the actual fiscal stance taken by the government irrespective of the business cycle fluctuations, the latter component reacts to business cycle fluctuations and is not directly under the control of policymakers (for example, unemployment benefits are non-discretionary spending that will automatically increase under a recessionary phase of the business cycle to stabilise the economy).

Analysing India’s fiscal policy

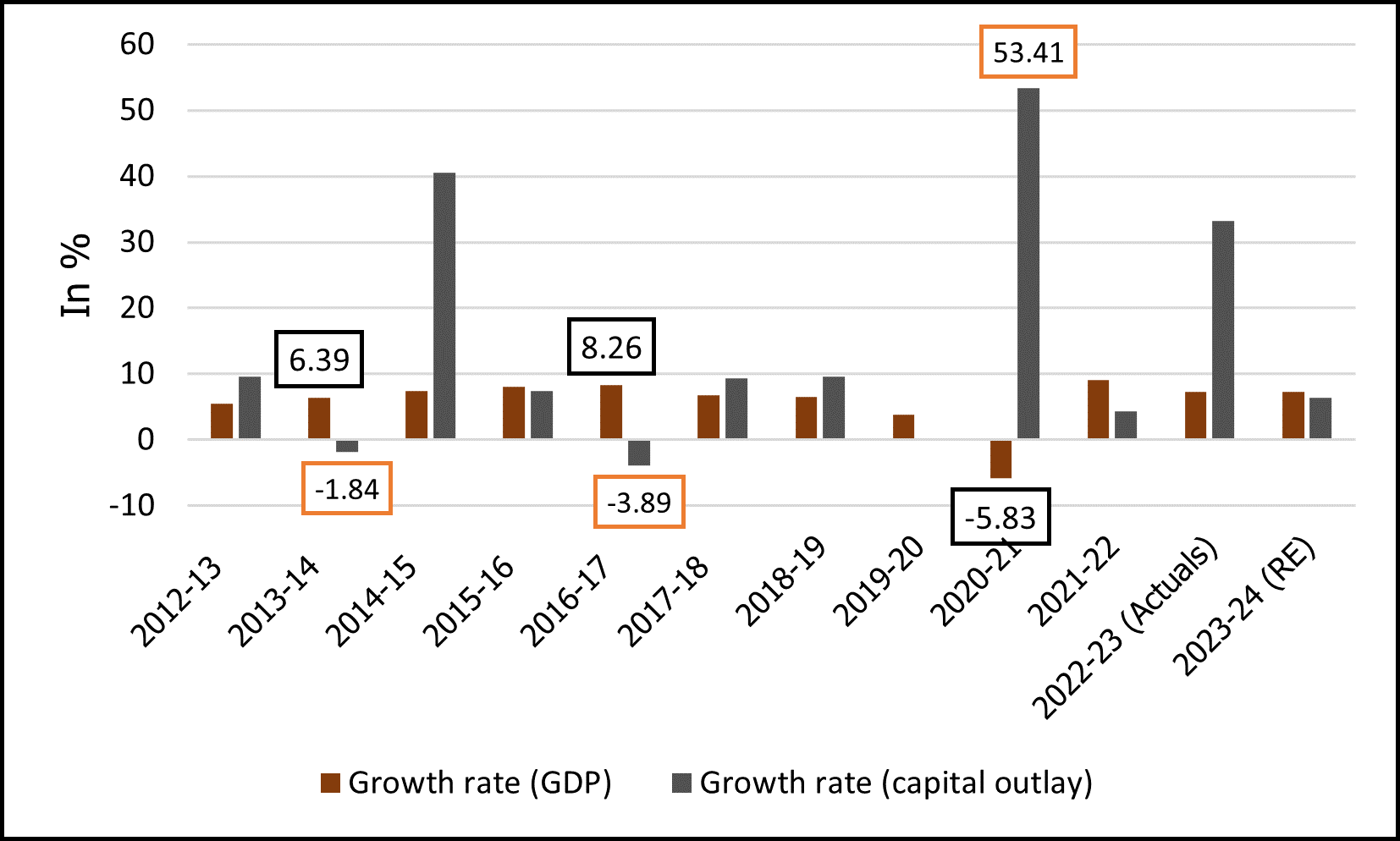

To systematically analyse whether India follows a procyclical or countercyclical fiscal policy, I evaluate the discretionary component of the fiscal variable for the period 2011-12 to 2024-25 (as per BE). As an initial exercise, we evaluate the pattern of the relationship between real GDP growth and the growth rate of total capital outlay. Since the expenditure on capital outlay is fully under the control of the central government (in other words, discretionary), the government can curtail it during times of financial distress. To facilitate comparison, we employ the data for annual real GDP (2011-12 prices) and capital outlay for the period 2011-12 to 2023-24 (RE)3. The data for both variables were sourced from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). Further, the data for capital outlay is deflated by the Wholesale Price Index (2011-12 base year) to convert it from nominal to real terms. Figure 1 showcases the trends in the growth rate of real capital outlay in the current period and (lagged) real GDP growth. The reason for using last year’s real GDP growth is that the Union Budget can undertake a course correction only with a year’s lag (Kamila et al. 2023). A cursory look at the series suggests that the two series are approximately moving in the same direction, with a few exceptions.

Figure 1. Trends in the (lagged) growth of real GDP (in %) and capital outlay (in %)

Only in three out of 12 instances, the growth rate in real capital outlay and real GDP growth are negatively associated or, in other words, countercyclical. In the years 2013-14 and 2016-17, when real GDP growth was 6.39% and 8.26%, the associated growth rate in capital outlay in the following years were -1.84% and -3.89%, respectively, indicating countercyclical fiscal policy. Likewise, a negative real GDP growth in 2020-21 was followed by a whopping 53.4% increase in capital outlay growth in 2021-22.

However, Fedelino et al. (2009) and Fatás and Mihov (2013) report that certain components of fiscal policy, such as social sector expenditures on health, education, unemployment benefits and family programmes, respond immediately to changes in macroeconomic environment to stabilise the economy, and are not the direct result of policymakers’ deliberate spending decisions. These cyclical, non-discretionary, built-in mechanisms in the government’s policies are known as ‘automatic stabilisers’. The impact of these automatic stabilisaers, therefore, needs to be filtered out to evaluate the actual fiscal stance of the government. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates data for ‘cyclically adjusted primary balance’ (CAPB) as a percentage of potential GDP, which partials out the cyclical effects in the economy along with net interest payments from the overall deficit of the government. This conceptually informative indicator thus enables us to assess the impact of aggregate demand on discretionary fiscal policy, and gauge whether the stance of the government is expansionary or contractionary.

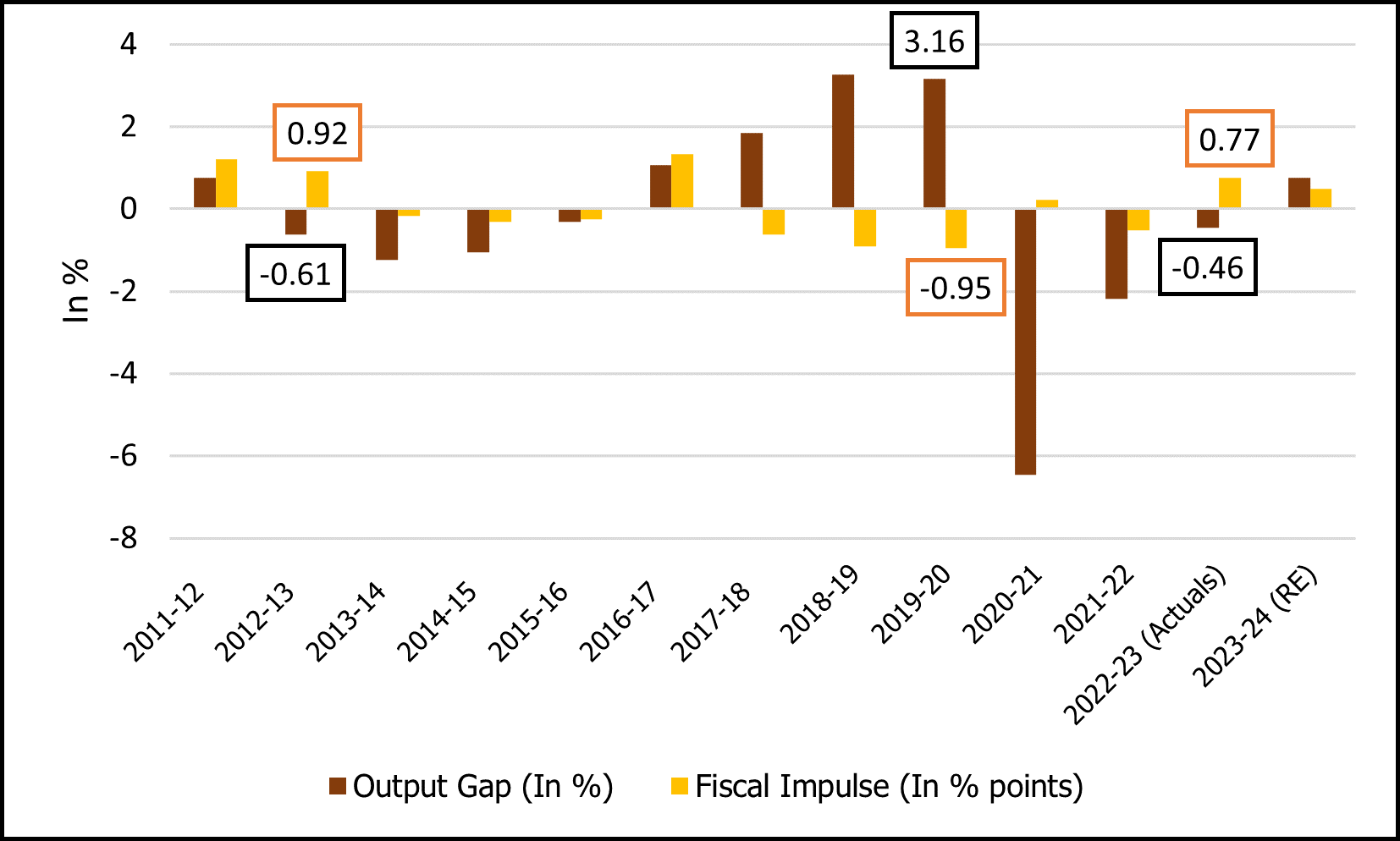

Additionally, to understand the nature of fiscal stance (expansionary versus discretionary), it is imperative we look at ‘fiscal impulse’ (difference between CAPB over two periods) along with a measure of economic activity relative to the potential output in the economy (that is, the output gap). A positive output gap signifies that current economic activity in the economy exceeds the potential output (full capacity output) (de Brouwer 1998). Thus, if a positive output gap (booming economic activity) in the previous period is followed by a positive fiscal impulse (expansionary fiscal policy), the government is said to have a procyclical fiscal policy stance. On the other hand, if a positive output gap is followed by a negative fiscal impulse, signifying fiscal consolidation, the government is pursuing the much-needed countercyclical fiscal policy. In Figure 2, we map the association between (lagged) output gap and fiscal impulse for the period 2011-12 to 2023-24. We find that fiscal policy of the central government exhibits countercyclicality in six out of 13 years once we control for the impact of cyclical fluctuations.

Figure 2. Trends in (lagged) output gap and fiscal impulse

Towards a higher degree of countercyclicality in fiscal management

The government’s resolve towards implementing a countercyclical approach was evident in the Economic Survey 2020-21 where it highlighted the dire need to avoid being fiscally conservative during an economic crisis. Citing the example of Indian kings who invested large sums in the construction of palaces during periods of droughts and famines, the government underscored the importance of an expansionary fiscal stance during a crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic, as the fiscal multipliers have a significantly higher impact on aggregate demand during a slowdown in the economy vis-à-vis a boom.

Government’s expenditure policies have a significant bearing on the well-being of the population, and on macroeconomic stability of the economy. While advanced economies can boast of this budgetary feature for a long time, emerging economies such as India also seem to be on track toward sound debt management and a higher degree of countercyclicality in their fiscal management.

The views expressed in this post are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of the I4I Editorial Board.

Notes:

- Budget estimates refers to the amount of money allocated in the budget to any ministry or scheme for the coming financial year. Revised estimates are mid-year review of possible expenditure and need to be authorised for expenditure through parliamentary approval.

- Fiscal deficit (comprising revenue and capital deficit) is the excess of government expenditure over revenue in a year. Revenue deficit is the government’s total revenue expenditure over its total revenue receipts.

- For the financial year 2023-24, the National Statistical Office has forecasted a real GDP growth rate of 7.32%.

Further Reading

- De Brouwer, G (1998), ‘Estimating Output Gaps’, Research Discussion Paper 9809, Reserve Bank of Australia.

- Fatas, Antonio and Ilian Mihov (2003), “On constraining fiscal policy discretion in EMU”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 19(1): 112-131.

- Fatas, A and I Mihov (2009), ‘The Euro and Fiscal Policy’, NBER Working Paper 14722.

- Fatás, Antonio and Ilian Mihov (2013), “Policy volatility, Institutions, and Economic Growth”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2): 362-376.

- Fedelino, A, A Ivanova and M Horton(2009), ‘Computing Cyclically Adjusted Balances and Automatic Stabilizers’, IMF Technical Notes and Manuals 09/05).

- Fernández, A, D Guzman, RE Lama and CA Vegh (2021), ‘Procyclical fiscal policy and asset market incompleteness’, NBER Working Paper 29149.

- Galí, Jordi, Roberto Perotti, Philip R Lane and Wolfram F Richter (2003), “Fiscal Policy and Monetary Integration in Europe”, Economic Policy, 18(37): 535-572.

- Huidrom, Raju, M Ayhan Kose and Franziska L Ohnsorge (2018), “Challenges of fiscal policy in emerging and developing economies”, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 54(9): 1927-1945.

- Kamila, Anshuman, Ritika Bansal and Rajiv Mishra (2023), “A Reformist Thought to Fiscal Reform and Budget Management”, Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers, 48(4): 247-254.

- Keynes, JM (1936), The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Macmillan.

- Talvi, E and CA Vegh (2000), ‘Tax base variability and procyclical fiscal policy’, NBER Working Paper No. 749

26 March, 2024

26 March, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.